When We Talk About Women Photographers

Carrie Crow

June 2016

What We Talk About When We Talk About Women Photographers:

On Helping and Hindering Their Legacy

It has been one of my special hobbies, and one I have been very emphatic about, not to have my work represented as ‘woman’s work.’ I want it judged by only one standard, irrespective of sex…Personally I would not want anything said of me unless it were simply that I was a serious student of painting and am now a most serious worker in Photography. – Eva Watson-Schütze

The Jurors – Eva Watson-Schütze, 1899

The Jurors – Eva Watson-Schütze, 1899

Left to right, Clarence H. White, Gertrude Käsebier, Henry Troth, F. Holland Day and Frances Benjamin Johnston

When Eva Watson-Schütze was asked to submit images for the ‘American Women Photographers’ exhibition Frances Benjamin Johnston was organizing for the World’s Fair in Paris in 1900, Watson-Schütze objected to having her work appear in a women-only show. Johnston enthusiastically promoted women in photography, equating the medium as a means for women to liberate themselves from traditional social roles and affording them precious independence. The exhibition was a chance to show the world what women were capable of behind the lens. Despite the worthiness of Johnston’s vision, Watson-Schütze had no need to associate with a women’s photography movement. Her work had already won international exposure and acclaim, she was counted alongside both male and female contemporaries as one of the great early American photographers and within the next two years, she would help co-found the Photo-Secession movement with Alfred Stieglitz, a group that was pivotal to elevating the perception of photography into that of a fine art.

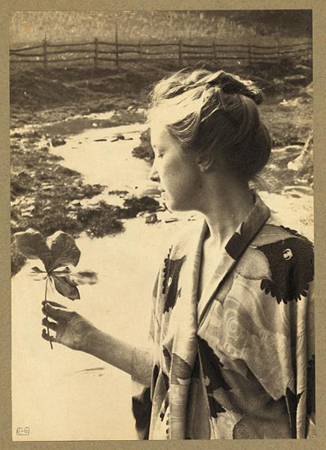

The May Apple Leaf – Eva Watson-Schütze, 1900

The May Apple Leaf – Eva Watson-Schütze, 1900

It’s easy to sympathize with Watson-Schütze’s objection to participating in the women-only show. On the one hand, she could have been a key representative of pioneering women in photography at a critical moment on the international stage. On the other, she was adamant that her work stand on its own merit without risk of being sidelined by gender association. And in this paradox lies one of the critical problems in thinking about, talking about and anthologizing women photographers: grouping them by gender both helps and hinders their legacy.

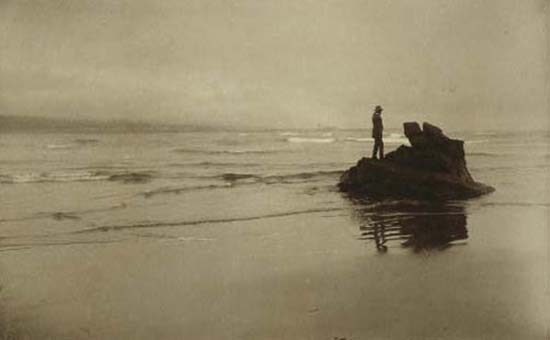

Looking Seaward – Myra Wiggins, 1889

Looking Seaward – Myra Wiggins, 1889

‘American Women Photographers’, Paris 1900

Assembled by Frances Benjamin Johnston in just six weeks (an astonishing feat considering the logistics of collecting the work from all over the country and shipping it overseas), ‘American Women Photographers’ featured nearly 200 photographs by 29 women. Johnston included leading commercial professionals, art photographers, and amateurs from across the country and based her selections on artistic merit. A few of these women have already been covered in this series like Alice Austin, Zaida Ben-Yusuf, Gertrude Käsebier, and Frances Benjamin Johnston in addition to Watson-Schütze, who ultimately gave in to Johnston’s persistence and contributed 12 pieces for the show, more than any other artist. For Watson-Schütze, participating in the women’s show was perhaps mitigated by the fact that she was to be the only woman in a concurrent exhibition at the Boston Arts Club.

Girl in Period Dress with Headband – Emily Mew, 1900

Girl in Period Dress with Headband – Emily Mew, 1900

Promising a look at the “New Woman”—the liberated, turn-of-the-century feminist ideal of which Johnston was a natural spokesperson—and insight into how American women were faring in the mastery of photography, a medium considered to be a symbol of modernity, ‘American Women Photographers’ was eagerly anticipated and widely attended. In fact, the crate of photographs assembled by Johnston arrived a few days in advance of her and was opened by impatient congress delegates before she stepped off the boat in France.

At Dusk – Emma Justine Farnsworth, 1894

At Dusk – Emma Justine Farnsworth, 1894

Back in New York, Alfred Stieglitz was boycotting the Universal Exposition altogether. He had been offered eight weeks to assemble and exhibit a selection of work by American photographers, however after his request to have the work hung in the fine art halls with painting and sculpture rather than segregated in a photography-only presentation, he stayed home. Stieglitz’s rival, F. Holland Day, who was also jockeying for a leadership role in the burgeoning photographic movement didn’t head to Paris either. Instead he was bringing a selection of 400 photographs to London for ‘The New School of American Photography’ exhibition he arranged in an attempt to further the reputation of American work abroad. With the two leading men occupied in their own political pursuits, Frances Benjamin Johnston presented the only significant collection of American pictorial photography at the International Congress of Photography of the 1900 Universal Exposition in Paris.

Milkweed – Mary Carpenter Paschall, 1900

Milkweed – Mary Carpenter Paschall, 1900

After the initial showing at the Exposition, an encore display was arranged in Paris at the Palace of Letters, Science and Art and by special request from a Russian enthusiast, it traveled to St. Petersburg and Moscow. Critics noted the American women were far more advanced than their French counterparts and singled out the accomplishments of many of the women in this series. The Bulletin du Photo-Club de Paris remarked, “The woman photographer does not exist yet in France, except simply as an amateur, but she already exists in England and America.” While critical and public reactions to ‘American Women Photographers’ were enthusiastic, this groundbreaking exhibition was ignored and forgotten at home.

‘American Pictorial Photography Arranged by The Photo-Secession’, New York 1902

By way of comparison, two years later, Alfred Stieglitz assembled the ‘American Pictorial Photography’ show at the National Arts Club in New York, for which he had unlimited selection of the finest practitioners of pictorialism in the country. The exhibition featured 162 prints by 32 photographers, of which 9 were women—including Gertrude Käsebier and Eva Watson-Schütze—an impressive ratio by today’s standards, however at the time, a common occurrence. Even in the earliest photographic salons in America, women were well represented. Eva Watson-Schütze’s silhouette of five salon jurors in 1899 is a testament to the prominence of women in the most important salons; of the five jurors, two are women, Gertrude Käsebier, and Frances Benjamin Johnston.

Out of the Past – Rose Clark and Elizabeth Flint Wade, 1898

Out of the Past – Rose Clark and Elizabeth Flint Wade, 1898

Stieglitz was deeply committed to the fine art potential of photography and wanted it to be equated with that of painting. In fact, his friction with the most powerful photographic salons at the time was based on just that: the work that he valued for painterly aesthetic qualities and technical innovation was rejected by traditionalists who prized documentary-style photographs that most accurately depicted real life. Stieglitz therefore approached his first exhibition with the inclusiveness of one who wants to illustrate the vast potential of the medium rather than restricting it to those who are simply “best in show.”

Both masters and amateurs of the craft were represented and despite some unevenness amongst the work displayed, critical response was overwhelmingly positive. Stieglitz gushed, “The art critics, the best of them, are studying the pictures carefully, and some excellent articles have been written, and will be written, on the subject. Even the ‘Century’ is to open its pages to ‘Photography as a Fine Art.’” Critics remarked it was “the choicest collection ever assembled under one roof.”

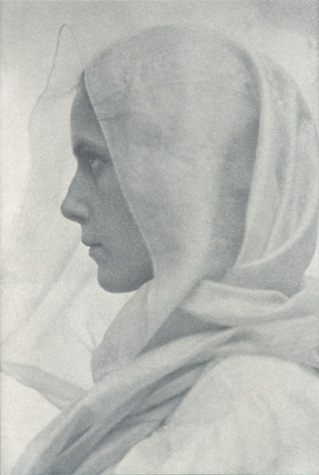

Serbonne – Gertrude Käsebier, 1901

Serbonne – Gertrude Käsebier, 1901

This important exhibition demonstrated what the future of photography could be. It was a watershed moment and coupled with the founding of the first major photographic movement in America, cemented the exhibition’s place in history and established Stieglitz at the center of the birth of photography as a modern art form. Many of the artists exhibited enjoyed long and celebrated careers such as Edward Steichen, Clarence White, who went on to found his own photography school), Gertrude Käsebier, F. Holland Day, and of course Stieglitz himself.

It’s unfortunate to note that the 2002 book, Stieglitz and the Photo-Secession, 1902 omits the work of three of the nine women presented, whose images could not be accurately identified.

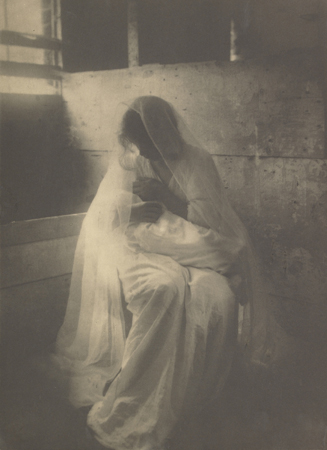

The Manger (Ideal Motherhood) – Gertrude Käsebier, 1899

The Manger (Ideal Motherhood) – Gertrude Käsebier, 1899

What I Talk About When I Talk About Women Photographers

Two landmark exhibitions, two groundbreaking moments in the history of photography. One is utterly forgotten, the other continues to be celebrated today. Why go on about something that took place more than 100 years ago? Simply put, I love the work of these women and believe it needs to be seen more. They were acknowledged masters of the craft in their day and their images deserve to be seen as often as the leading men of the time, by which I mean at every museum or gallery around the world with a permanent photography collection. I imagine how it would inspire photography students, especially women, to consider that if Frances Benjamin Johnston could wield several pounds of equipment, mount an international exhibition in six weeks all while wearing heels and a Victorian dress, they might feel they could do anything.

However, I cringe every time I write “woman” before the word photographer. I respect the work too much to blatantly disregard their wishes not to be remembered as women photographers but as photographers. And yet, I have found no way thus far to discuss the work without acknowledging that it is a gender bias that suppresses their accomplishments and keeps them out of the history books.

For example, where in the history of photography does it acknowledge the correspondence between Watson-Schütze and Stieglitz in which it is she who is encouraging him to go over the heads of the regional salons and establish the national movement that would become the Photo-Secession? Their letters formed the basis of the movement’s mission: “I feel very strongly that now is the time for action,” she wrote in one letter, urging him on. At that time, she was living in Chicago where she had followed her husband who had taken a new job as a professor, and although not at the physical center of the Photo-Secession movement, she was integral to its founding.

Consider also how some women referred to themselves and their photographic work in correspondence. Their letters illustrate the fact that domestic obligations and personal demands were far more pressing than establishing their own legacy.

To be known means more care and more demands upon me and I have too many already.

– Sarah Jane Eddy, in a letter to Johnston declining to send a biography with her submission for the 1900 ‘American Women Photographers’ exhibition.

I would enjoy doing some new printing of pictures. But this is a busy month—my boys & girls busy in various ways about their schools & all of us in a hurry to get to our lake home so I cannot do as I would like.

– Mary Bartlett, in a letter to Johnston expressing a desire to have better prints for the 1900 ‘American Women Photographers’ exhibition.

Even early critical writings couldn’t transcend gender issues already prevalent within the medium and remember, this is at a time when women were actually well integrated with their male peers. Writer Helen L. Davie observed in the 1902 photographic monthly Camera Craft, “To the influence of women is this advance in the status of Photography largely traceable. Women, the conservative, the copyist, as many are pleased to term her, has in this instance been the pioneer, leading the way in pictorial portrait Photography [sic], a way which her brothers have found pleasant and are making haste to follow.”

Davie continues, “The recent date of woman’s influence is marked by the fact that it is but ten years since the photographic authorities abolished their medals for women, recognizing that their work was on par with that of the men and applying the same standard to workers of both sexes, since which time the women have had their full share of photographic honors.”

In the midst of writing this piece, I was alarmed by something I read about a recent panel, Women in Photography & Filmmaking,” held in March at the International Center of Photography. Panelist Maggie Steber described being physically assaulted by a male colleague when she arrived earlier than him on a TV set and set her equipment up in what he perceived as “his” spot. Patricia Silva, who wrote about the event for ICP’s website observed, “it was not the first, or the tenth, time I’ve heard stories of physical violence toward a female photographer.” I wonder to what extent the suppression of women’s activities in the history of photography has aided and abetted a scenario in which men view their female colleagues as interlopers in “their” territory. Is it possible that the absence of women in the medium’s history has led men to view them as a sudden threat to their livelihood rather than contemporaries in a field who were present all along?

Do we need to talk about women photographers as women photographers? If we don’t, assuredly no one else will. Yesterday’s women photographers deserve it and today’s women photographers need it. And if we don’t pursue equitable representation of women’s photographic work in the context of the medium’s history in order to acknowledge their specific, but as yet uncelebrated individual achievements, it would be as if they were never even there. This suppression may well have even contributed to the hostility that exists between male and female practitioners today. We urgently need to continue to unearth the contributions of women throughout photographic history and if they must be categorized as “women photographers” for now to get them into the historical mix, then let it be so.

For now.

Woman Draped – Amelia Van Buren, 1900

Woman Draped – Amelia Van Buren, 1900

Women Were Photography Pioneers Too Series links:

Eva, Anna, Margrethe, Doris: The Gospel According to Women Photographers

Part Two – May 2016

Carrie,

Thank you for such an enlightening writing & presentation of amazing works! I totally agree w/ you…

Yuko Otomo

Yes, and the proof is in the photographs you have included in the article…simply sublime!

Thank you, Carrie