William Bailey: Looking through Time

Daniel Barbiero

November 2019

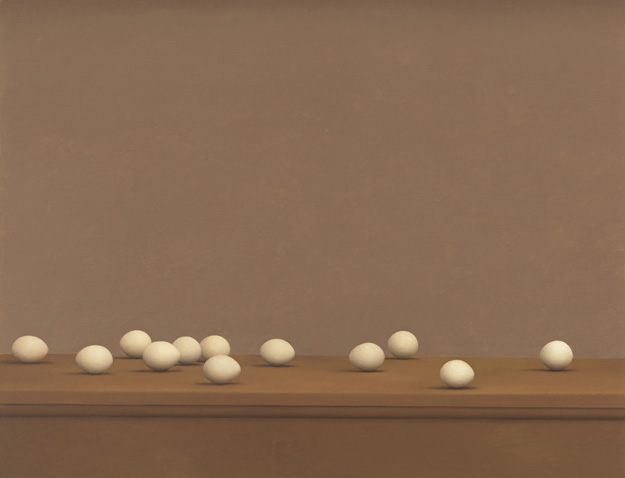

Plateau, 1993, image courtesy of Yale University Art Gallery

Plateau, 1993, image courtesy of Yale University Art Gallery

Imagination, Memory and the Non-Being of Ordinary Things

Although he is frequently classified as a realist because of his meticulously depicted still lifes and figure paintings, William Bailey is no realist in any ordinary sense of the term. To be sure, his drawings and paintings allude to the world of material facts but that is precisely what they do: allude, from a certain degree of removal. Paradoxically, his paintings, and particularly his still lifes, represent a perspective that has more in common with the metaphysical than with the rawly physical. Bailey’s still life paintings are the focus of Looking through Time, a survey of his work mounted by Yale University, where he was trained and where he is the Kingman Brewster Professor Emeritus of Art.

Ordinary Things in an Empty Theater

Bailey’s still lifes are notable for the way that they cast everyday objects as mute actors in an otherwise empty theater. The human presence is felt only through its complete absence. To an extent, every still life does this. What makes Bailey’s notable is the lack of the kind of narrative that can often be found, implicitly to be sure, in more ordinary still lifes. These latter often seem to offer views into something already in progress, scenarios in which the objects depicted have a function and are depicted in the middle of filling those functions: the ordinary still life is still to the extent that it seems to show life, interrupted in medias res.

By contrast, Bailey’s still lifes reject the implication of narrative. He himself has said that his paintings are motivated by “simple propositions” and are “not about stories.” If ordinary still lifes imply ordinary things’ roles as instruments and obstacles within the world of human projects, Bailey’s would seem to show them rather as things in themselves. They would appear to approach the idea of the Sartrean en-soi, the gratuitously material in-itself rather than the thing-for-us, the inert object complete in itself and identical with itself, pointing only to itself and not to some as-yet-unobtained state to which it must move. It simply is what it is, with no hidden messages or occult significance. While this may appear true at a purely visual level, at a deeper level it’s deceptive; on the one hand Bailey’s objects do seem to carry a certain kind of empirical force, and on the other they are not the transcription of the perceived world they may seem to be.

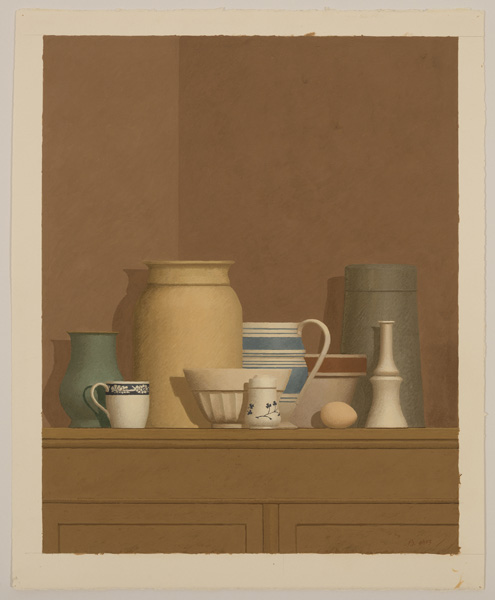

A tempting case for the paintings’ realism—for their grounding in the empirical realm of observed reality–can easily be made just by looking at them. Take, for instance, Plateau, a tabletop still life from 1993. The painting shows ten eggs scattered across the table, in front of, behind and beside a number of everyday objects: a tall blue cylindrical candleholder; a scallop-sided coffee cup; a white saltshaker with blue markings; a light blue pitcher mottled with olive brown; a white bowl patterned with irregular blue spots resembling a leopard’s spots. All of this against a dull maroon wall as background. As with many of Bailey’s still lifes, the overall tone is subdued with the occasional breakthrough of color in the guise of the objects’ dense blues. Plateau would seem to convey what Wallace Stevens called “the eye’s plain version” of the world, perceived in a play of solid surfaces and projecting volumes.

Eggs, 1974, image courtesy of Yale University Art Gallery

Eggs, 1974, image courtesy of Yale University Art Gallery

This preference for the (apparently) plain view is epitomized at its most elementary in Eggs (1974). Eggs depicts a relatively simple linear arrangement of twelve eggs distributed on a tabletop. Bailey began painting a series of eggs in the 1960s after a conversation with artist Conrad Marcarelli, who suggested the egg as an example of pure form. But if Bailey’s decision to take eggs as a subject was motivated by a desire to work with a pure form, from another perspective the eggs themselves are somewhat incidental to his concept of composition. As he told Dorie Baker in a 2010 interview, “the relationships between the objects are more important than their individual identities.” Individually the eggs in the painting are simple, symmetrical objects of a single, curved surface, but as structural elements they take on a complex role in defining and dividing the space that contains them. As a collective mass, they trace a low, horizontal axis bisecting the picture plane and tracing a rough parallel to the surface on which they are arrayed. Bailey groups them in cluster and pairs or isolates them as individuals; this leaves a series of irregular negative spaces between them that take on a structural importance nearly equal to the eggs themselves. Bailey seems to have intended these spatial relationships to imply a temporal dimension for, as he told Baker, “with the egg paintings, I started thinking about time and slowing the paintings down and allowing the relationships to develop in time.”

If the structural composition of Eggs is a fairly simple one, many of Bailey’s other still life paintings feature more complex arrangements that suggest architectures. The collection of objects in Nocera umbra (1998), for example, are arranged on three vertical levels to form a kind of terraced pyramid. Still life—Castiglione (1983) compacts its pitchers, cups, jars and bowls into a tightly formed, dense mass that suggests the opaque, thick walls of a mastaba. In this latter picture structure seems to turn in on itself, as its defining formal relationships are all internal to the composite mass of things that sit like a super-object at its center.

Still life—Castiglione, 1983, image courtesy of Yale University Art Gallery

Still life—Castiglione, 1983, image courtesy of Yale University Art Gallery

The Non-Being of Ordinary Things

In their handling of everyday objects, Bailey’s still life paintings are reminiscent of the metaphysical paintings of Carlo Carrà and Giorgio Morandi. There are some superficial resemblances, to be sure: the clarity of the spaces in which Bailey’s objects are defined and delineated recalls the sharply structured spaces Carrà used to separate, decontextualize and consequently to define his objects, while the recurring repertoire of mundane things that Bailey depicts in different combinations and groupings recalls the closed set of ordinary objects Morandi returned to over and over again in both his metaphysical and post-metaphysical still lifes.

These superficial resemblances would seem to be the outward mark of a deeper quality that Bailey’s still lifes share with Carrà’s and Morandi’s. What Bailey’s still lifes seem to embody is something akin to the metaphysical attitude Carrà articulated in his statement “Della ‘cose ordinarie’”–“On ‘Ordinary Things.’” In essence, Carrà asserted that ordinary things “reveal that form of simplicity that speaks to us of a superior state of being.” Like the objects Carrà depicted, which could be as simple as a cube or cylinder, Bailey’s objects have an essential plainness and simplicity to them.

Where Carrà’s metaphysical attitude started from the anti-metaphysical intuition of the primacy of the ordinary thing in its solid materiality, Bailey’s seems to start from the opposite pole: from the primacy of imagination. While the objecthood of Bailey’s objects—their apparently gratuitous, sheer materiality—would seem to be guaranteed by their plain depiction as things alone and alone in themselves, there turns out to be no such guarantee. For, rather than being taken directly from observation of an empirical reality thick with worked matter, they are instead the product of Bailey’s preferred method, which is to work from imagination and memory rather than directly from life. Although he might start from life, he will work on the piece and ultimately finish it from memory and imagination. Thus the solidity that Bailey’s objects imply is an illusion. Not only a painterly illusion—the mimicry in two dimensions of what actually exists in three dimensions—but a conceptual illusion as well. If realism at least purports to ground itself in the sensual world of observation, then Bailey’s aren’t the realist paintings they may seem to be. And in fact they aren’t. As Bailey put it in a 2017 conversation with John Seed, “these are not meant to be realist paintings. They are about imagery.”

Imagination, Memory and the Quasi-Real

Bailey’s objects are ordinary things that are not actual things, but instead are projections of actual things. That just follows from the fact that his still life paintings are works of imagination rather than of observation; they therefore present the paradox of portraying the solid being of material things through the non-being of the imagined thing. (Because these still lifes to all appearances portray the objects they represent in all their brute materiality, the language of ontology—of being and non-being—doesn’t seem out of place in trying to understand them. We know what these things appear to be; what we want to know is what they really are.) Their ostensibly realistic surfaces are in fact the product of the complex and paradoxical relationship of imagination to the world: a dialectical relationship of non-being to being.

The world of imagination is the world of non-being in that what we imagine is an image of being and not a confrontation with being itself. Imagination is not what it is that it imagines, in a manner obviously analogous to the way that Magritte’s painting of a pipe is not a pipe. But the difference between the imagined object and the depicted object is that imagination is as much an active projection as it is a representation.

Imagination can project forward, as when we hypothesize or plan something that might be brought about in the future; in the case of memory, which is itself a kind of imagination, it is a matter of the projection into the present of the image of something past. As it is with imagination, the reality that memory recreates isn’t the reality of observation—the reality of the common sense empirical world we confront in everyday life—but rather a sign, more or less condensed, more or less detailed and accurate, of disappearance. What is present in memory is in fact a sign of absence: the missing object as represented by its image. Such a representation inevitably involves a degree of abstraction since memory, as an active projecting forward of the absent past, doesn’t passively reproduce in its details what is no longer there, but instead recreates and reimagines it, subject to the contingencies and needs of the present into which it projects. In effect, the remembered image is not the direct image of the objects or events it recalls but instead is a refracted image: an image of indirection.

Nocera umbra , 1998, image courtesy of Yale University Art Gallery

Nocera umbra , 1998, image courtesy of Yale University Art Gallery

From the Quasi-Real Back to the Real

In the cases of both memory and pure imagination, then, what we have is a projection of what has been or what has not yet been—two modes of what is not. In short, in positing a non-present object, event or state of affairs, imagination and memory are projective acts of non-being onto being—a way of throwing an image of the hypothesized onto the screen of the actual. (In this sense, imagination would seem to refute Parmenides’ dictum that one cannot think what is not.)

This observation would count as a commonplace if not for the tension Bailey’s still life paintings set up between the apparent solidity and materiality of the objects they depict and their practical roots in the immaterial imaginary. This tension is the product of a kind of duality that Maurizio Ferraris characterizes as an extropic strabismus, or double vision: one eye, the eye of intuitive ontology, sees a world furnished with solid objects, while the other, epistemologically-inclined eye sees phenomena shaped by the faculties of perception and conceptualization. Bailey’s starting point does appear to be informed by the seeing the everyday ontology of solid independent objects. But rather than the second eye seeing through the mediation of epistemology—of conceptual schemas corresponding more or less neatly to the world—it sees through the mediation of imagination and memory. Ontology’s other here is the creative projection rather than the cogito of the transcendental knowing mind.

This tension between the appearance of the concrete real and its dematerialization in imagination and memory is a tension that ultimately is as productive as it is provocative: in the end, a complementarity rather than a contradiction. Bailey’s ordinary things may be things immediately grounded in the non-being of imaginative projection or memorialized absence, but they are also an opening through which to reconsider the being of the most mundane things—the cups, pitchers, bowls, funnels, candlestick holders, coffee makers—that populate his still lifes. Imagination isn’t a flight from the concrete so much as it is an invitation to see again through the eye of intuitive ontology. It is if anything a reminder that the objects and events that make up the concrete being we encounter in our everyday, intuitive ontology provide the preconditions for the imaginative and recollected projections that rearrange—sometimes intentionally, sometimes not—the things we’ve encountered. Our relationship to that world turns out to be an admixture of encounter and projection: a mutual permeation of the real and the quasi-real.

In essence, in working from imagination and memory, Bailey is neither realist nor anti-realist, but rather a depicter of quasi-real fictions drawn from the world of intuitive ontology. Fictions that carefully, and convincingly, reproduce an image of the volume and solidity of the empirical. To portray things through imagination and memory and without direct reference to their actuality; to validate the depiction of being by way of the non-being of imagination and then, through the appearance of realism, finally to have that depiction serve as an opening back out to the world of solid being: this is the paradoxical project of Bailey’s still lifes.

William Bailey: Looking through Time→

Yale University Art Gallery

September 6 – January 5, 2020

◊

Daniel Barbiero is an improvising double bassist who composes graphic scores and writes on music, art and related subjects. He is a regular contributor to Avant Music News and Perfect Sound Forever. His latest releases include Fifteen Miniatures for Prepared Double Bass, Non-places with Cristiano Bocci & their most recent collaboration, Wooden Mirrors.