Uncollected Thoughts on Gregory Corso’s “The Golden Dot”

Ivan Klein

November 2022

Gregory Corso died at the age of 70 in the year 2000 from prostate cancer. In these last poems, he deals with his imminent mortality, gruesome and romantic memories, testamentary history, and what might be termed cosmic reflections.

Publication was delayed for over twenty years due to inheritance issues and disputes over editorship of the diffuse manuscript, but we have it now in a handsome and respectfully put together edition from Lithic Press.

Call it last deal gone down.

The introduction by Raymond Foy uses an excerpt from the title poem as its epigraph —

This is how it happened:

At the end

everything that was

dwindled into a dot,

The dot exploded into the void

and the beginning began again —

A speculative shot in the dark, even given modern astronomical knowledge. Reminds me just a bit of the most ancient Rig Veda’s “Hymn of Creation.” — That is, an intuitive attempt to grope intellectually and spiritually toward the nature of how the worlds came into being.

• • • •

Corso, from “Elegiac Feelings American” for the dear memory of John Kerouac: “a gallon of desperate whiskey a day it took ye to look that America in its dissembling eye”

-1970

That disaffected feeling right down to the bottom of his soul would manifest itself to the very end.

The Golden Dot —

These late poems of the veritable self mostly blunt, to the point, beyond artifice.

Writing poetry as a locked up

foster child before

he knew

there was even such a thing as …

The only poet I have known and have

Is myself

This book, these poems are a constant flow

Re-dundant, chaotic, profoundly heartfelt

And what better response to illness and the anticipation of his end than the truth of poetry? — A deeper image than that accusing decay of life that is one’s mirrored reflection.

Ah, what a muddle is life and death —

How we mutter and stumble toward

blessed silence!

Foster homes without books. Locked up in the Tombs at age thirteen, that infamous downtown jail wherein Melville’s Bartleby came to his obscure end. Corso tells us he picked up a book from a cart that was wheeled around to inmates and saw the poetic line for the first time:

I’m good proof of two things.

One, you can be born a poet

Two, when you’re alone poetry

can be your best friend —

A born poet he seems to have been. Enough pain and solitude, a certain gift, a certain faithfulness to the integrity of the moment and of his very self.

The poem “Ask me not of moons …” — A cosmic poet here as well as a personal poet — that unspeakable metaphysical sense, self-taught, felt down to his bones. — Not beholden to any doctrine of East or West. No show of religiosity as you get with his pals Ginsberg and Kerouac. Just an ex-con scratching to figure things out and rescue himself.

The Golden Dot — A contradictory internal monologue of poems. Corso, the man, succeeding above all in killing the time that’s killing him.

The poet sweating out the truth

of his moment

on this crimped earth.

He tells us that sometimes he thinks he cheated himself, dying in the fog of coffee-stained manuscripts, heartbreak memories, loose change that didn’t quite add up to the price of a square meal. — Resentment of an approaching death, of being cut out of the show. Who could blame him? — Resentment of a little pussycat, of a big old oak tree for the life that’s in them — unfiltered at the end. Nothing to hide, nothing to withhold.

He looks back:

The important thing was

one’s belief in oneself as a poet

and experiencing the blessed feeling of creation

………………

and … rare

I was given at birth

a gift or task

This last book just a bit uneven, occasionally nearly lost. — When death is staring a man in the face and he speaks to himself as well as to us, what is it that can be decently expected?

Do we wish him to make sense,

to fashion poetry out of

those onrushing sounds

that are to be his vey last?

— sometimes, astonishingly, he does just that.

Had you but loved the lesser love more

The nausea of lovelack would rack you less

When all’s sucked up like the pull of a black hole

What can escape from the emptiness you feel?

“Lovelack — pretty much from his abandonment at birth.

the emptiness of locked rooms in a string

of foster homes

— “lovelack” — and then the years in Dannemora’s big time lockup

as punctuation.

Lovelack pervading the entire strung-out universe.

— No question the poet would have agreed.

Strung out for a lifetime / set up /

the fix was in right from jump.

The only shot for me out of all of this is

Whether they love me or no

They’ll be spared their tears for me.

[His fellow Beats, friends, lovers, etc. who have already kicked

the living habit].

Long shot, terrifically long shot

as far as consolation can go

The very last poems of the downest of poets — who clung to poetry

as it clung to him. — No matter that they meander a bit, seem naturally

reluctant to come to a close.

Reading “The Last Gangster” in Corso’s Gasoline

I look down the street and know

The two torpedoes from St. Louis.

I’ve watched them grow old

… guns rusting in their arthritic hands

-1958

Only this denizen of ancient Bleecker St. could have written those lines, coupled with the sublimity of his “Botticelli’s ‘Spring.’” No wonder I dumbly carried a copy of the book to a reading by him, Allen Ginsberg and Peter Orlovsky somewhere downtown in the early 90’s. — Just an instinct born of admiration and perhaps a desire to read along. During the course of the evening, Corso tries to sell off his raw notes from a stack of yellow legal pads to members of the audience. — No takers and a desperate ploy it was. Reading Foy’s introduction to the new volume, I get some sense of how perpetually broke and strung out he must have been.

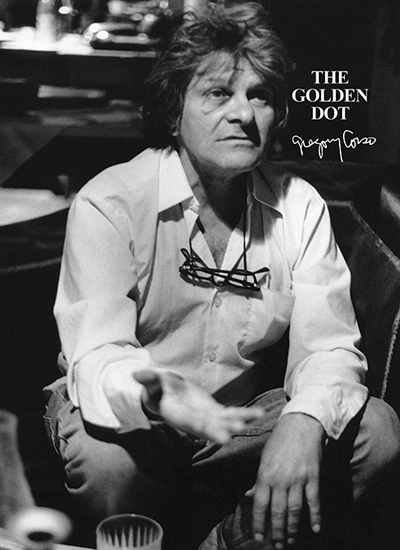

Afterwards, as people mill about, Corso sees me with that black and white City Lights edition of Gasoline and Vestal Lady On Brattle combined, calls me over and says, “You’re a nice guy, you don’t want to bother me,” and signs the title page. — City Lights, Pocket Poet Series #8. Now I hold it in my hands for a long time, the front cover a little worn, the volume a little worse for wear. I’m pretty sure the poems will endure whatever else rises and falls around them.

“Not recognizing the kind of person I was” — a confessional poem of the carceral kid, the youngest inmate in Dannemora, playing the ingratiating clown to get by — and who wouldn’t have done likewise?

“My manhood had been truncated. O damn’d life!”

Just that real.

The young poet of the hard knock.

Of coming from behind

right out of the cradle,

from the crack of the judge’s gavel.

— the original angel-headed hipster.

As I say, when I was young and tentatively, dreamily first putting pen to paper as if I really existed, Corso’s Gasoline was my standard. — That along with Ginsberg’s stuff and some of the other self-styled Beats. — They seemed inevitable — what was in the air, happening now. Would happen, I hoped even to me.

Corso in the homestretch:

the illness of the winds …

indeed — what I was born for,

besides poetry

is death —

Like I feel it is a race.

— With this, I would embrace my brother.

And again:

My papers of words was writ when I shot

a word like a star on the page …

Yeah, the Beats still matter, at least to me, in their unambiguous embrace of life. — In the beginning and until the very end was only the word and what was beyond the word.

Great and spacious

and blessed was that

Many of the late poems in Dot are directly autobiographical. — Methadone clinics, the father now with Alzheimer’s who whipped his sixteen-year-old wife so that she ran away and wasn’t a mother to baby Gregory. Then off to Catholic Charities which found a succession of foster families (six by his count) with dark and lonely rooms for him.

A child of the muse, he says.

Ginsberg called him Captain Poetry

The great question looming

over the broken poet:

how to kill the pain inflicted by this life?

From his poem “Notes After Blacking Out” in the volume The Happy Birthday of Death (1960) — “Yet truth’s author itself is nothingness.”

The noble struggle that “A finite head might encompass infinity.” (from “Dear Villon, Dear Milarepa”)

Dot — “Reader, when poetry came to me …” — in this poem he goes over that business of his abandonment from birth until age ten: two years or less

To 6 needy loveless families —

A man visited me once a year

He sat upright, hardlooking,

talking with my foster parents

… hardly did he look at me,

after coffees they said their goodbyes:

before he left, he entered my room with me

closed the door behind him and wham, wham,

two stinging slaps to my face.

“Behave” he ordered and left

Years later I learned he was my father.

Photo by Gerard Malanga of Gregory and his father, Fortunato, in the Unmuzzled Ox, winter 1981, an issue featuring an interview with Corso and poems and drawings by him. No date on the photo, but probably in the sixties when the poet was still a young man and before Fortunato had entered his decline. Corso is wearing a Harvard sweatshirt and has a thick chain around his neck; he had his right arm around his dad, who is smoking a cigar. A couple of drinks on the table at the Village restaurant, Emilio’s. — There’s the ghost of a smile on both their faces … the whole mess of brutality, abandonment and love there to be seen

.

The story of the withdrawal of the father, a staple of the Judeo-Christian psychodrama, here played out within those grim Catholic Charities placements and Malanga’s photograph.

But Gregory, bless him, was favored by the Muse.

An Internal Monologue:

— “And who may I ask are you? …”

— “What else is poetry but talking to oneself?”

— “I thought poetry was the poet in communion with God.”

So Corso has it. — I used to have a clever answer for the differences between a poem and a prayer, I really did. And I’m thinking hard about it as I write this. — But that answer long ago turned into tongue-tied dumbass silence.

“Old age wills but once …” — A poem that encompasses astrological dynamics, biology, the nature of fate and finally brings itself home:

The time is always near

To betray one’s dreams

stab oneself in the back —

As one fated to greet one’s mother

67 years after birth —

The outcast a poet by chance and necessity —

A reflex junkie creating himself

With wounded words, healing words.

He asks

Where are the protective arms of love

used to shield me from the elements

my self-destructiveness

………………

Never knowing a mother’s kiss

nor cradling arms

I was a deformity of love

— A devastating judgment on that poor orphaned life.

And yet, it was well done

for us, for who would follow.

Last poems / final thoughts /

truest feelings / finis

◊

For further information on The Golden Dot, Late Poems 1997-2000 →

Ivan Klein’s most recent collection is The Hat and Other Poems and Prose from Sixth Floor Press in 2021. His other books include Toward Melville (New Feral Press) and Alternatives to Silence (Starfire Press). You can also find his writing in Leviathan, Long Shot, Flying Fish, The Jewish Literary Journal, The Forward, and in the great weather for MEDIA anthology Paper Teller Diorama. He lives and writes in downtown Manhattan.