Three Ordinary Seasons in New Haven

Daniel Barbiero

December 2019

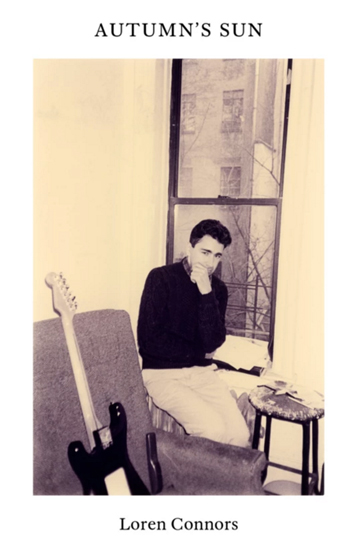

Review of Loren Connors, Autumn’s Sun, Blank Forms Editions

In the middle of the last century Wallace Stevens famously wrote in “An Ordinary Evening in New Haven” of a kind of dual reality: the reality of the concrete, empirical city given to the senses—the city as it appeared to “the eye’s plain version”—and the city as refracted through and colored by imagination—“the metaphysical town.” Stevens’ Professor Eucalyptus wanders throughout the poem’s thirty-one cantos uncovering the well-hidden (recall that etymologically “eucalyptus” means just that, “well hidden”) imaginative dimension—a dimension without which the truth of things would remain opaque–concealed within the physical reality of a place. The real New Haven of 1949 may or may not have been the actual inspiration for the Stevens’ poem but the city was in fact an apt setting for a meditation on the permeation of the mundane by the metaphysical. It is a permeation that by design lay at the heart of the city from its origin.

As founded in 1638, New Haven was quite literally meant to be a metaphysical town. It was established by a group of Puritans who envisioned the new plantation as an ideal city that would be ordered with the strong metaphysic of theological orthodoxy. The primacy of idea over matter was literally inscribed in the physical city from the outset; it was laid out in a grid of nine squares, the rectilinear shape of which represented the imposition of an ideal Form on the recalcitrant irregularity of the material landscape.

While the Puritans’ New Haven was the New Haven of biblical order, Stevens’ New Haven was the New Haven of high imagining. In both cases the physical town was, in effect, a pretext; the “real” city was the city as shaped by the structures of meaning lent it by human aspirations and engagements. Just about four decades after Stevens’ poem was composed, and three and a half centuries after New Haven’s establishment, Loren Connors depicted events in the life of the city and its environment, both human and natural, through his own web of meaning. If the Puritans’ New Haven was a New Haven of transcendental Ideal and Stevens’ metaphysical New Haven was a New Haven of the grand, truth-bearing imagination, Connors’ is a New Haven shaped by the more circumscribed imagination encountered through the everyday and conveyed in the unpretentious, mixed poetry and prose form of haibun: haiku interwoven with notes and reflections.

Connors is a New Haven native who lived in the city until relocating to New York in 1990. After early studies of violin and trombone he began playing guitar as well as bass guitar; by the late 1970s, he was playing blues-influenced, elastic-form solo improvisations on acoustic guitar and began releasing recordings on his own Daggett label in 1978. He’s still active as a guitarist and maintains creative collaborations with musicians in the rock and experimental worlds as well as with poets such as the late Steve Dalachinsky. Connors also has a background in visual arts, having studied art at Southern Connecticut State University (then Southern Connecticut State College) in the early 1970s; he claims the paintings of Mark Rothko as his most important artistic influence.

Autumn’s Sun was written in 1987, at a time when Connors largely abandoned music. New Haven at the time was still immersed in a decades-long aporia, an unsettled time of change brought on by deindustrialization, depopulation, general decline, and Model City efforts at urban renewal that razed old neighborhoods, displaced their residents, and permanently altered the landscape. Of directly musical importance, the city had also recently witnessed the dispersal of many of the musicians and musician-led institutions that since the mid-1970s had created and fostered an unusually active and fruitful community of improvisers and composers. Connors had had some involvement with them, but the response to his own form of blues-based improvisation was discouraging enough to make him look elsewhere for an outlet. During this time away from music he concentrated his creative energies on writing haiku and became an active part of the English language haiku movement, publishing in the Haiku Society of America’s journal Frogpond and winning an award for his work in 1987. Autumn’s Sun commingles Connors’ haiku written during the three seasons of summer, autumn and winter 1987 with prose fragments taken from his diary of the same period; the resulting haibun provides an apt vehicle for Connors’ leveraging the telling detail into an occasion of significance. The present edition of Autumn’s Sun is largely a reissue of a 1999 edition put out by Sonic Youth guitarist Thurston Moore and music critic Bryan Coley’s Glass Eye Books. For the current edition Connors made some changes to the original text and added the essay “The Dancing Ear: Blues and Haiku,” co-written with his wife Suzanne Langille, as an appendix.

At the time he was writing what eventually would become Autumn’s Sun, Connors was living with Langille and their son on Nash Street, not far from Mill River and the old oystering village of Fair Haven. His haiku and diary excerpts are full of precisely-observed details of what he saw and did in those well-worn parts of the town. They also document his excursions to the more rarefied milieu of Yale University, where he worked in a non-academic job during the 1970s and early 1980s but also spent time in its library and its well-stocked Yale Co-Op bookstore. (Which, in a sign of the changing times and of the city’s efforts to turn itself around, in the late 1990s became a large Barnes and Noble.)

It is through the diary excerpts that we get a strong sense of what it is like to inhabit an intimately known, very specific place. Connors writes of visits to local parks—Lighthouse Point, East Rock, Fort Hale, Sleeping Giant; describes listening to a Buxtehude cantata while watching traffic on I-95; makes note of his thoughts on passing by a carousel on the New Haven Green in December. He is as cognizant of the city’s cultural as well as its physical landscape. A significant part of what made New Haven what it was in the last century was the pervasive presence of first- and second-generation Italian-Americans, products of the great, largely Southern, Italian diaspora that made New Haven one of the most Italian cities outside of Italy. As late as the 1980s it was still not uncommon to hear Neapolitan dialect and accents on the streets of Fair Haven—itself undergoing an influx of Puerto Rican and other Hispanic settlers—Wooster Street, and elsewhere. This presence is something Connors observes and reflects on, as when he thinks about the grapevines so frequently found on trellises in the immigrants’ yards, or writes in July that

At Fort Hale I just couldn’t help thinking, when I saw a Mediterranean woman reach into the grass, of Italy and how Naples looked in 1925. I thought of roses in boxes, and the hot drinks. “Hot” seems to be the word. Even this jet plane going by. It’s hot…Really hot.

As this passage shows, Connors’ New Haven is a place permeated by chains of associations provoked by the contingent events he experiences. Many of them lead into and out of his own past growing up there. He recalls the Good Humor truck that used to drive down his street and the name of the man who drove it; remembers a visit to a hardware store on Grand Avenue—was it the 19th century-built Roland T. Warner Hardware Store, with its displays of rakes, shovels and other tools on the sidewalk by its storefront?—whose old wooden floor turned his ankle; and has an epiphany by the Quinnipiac River one July day, when he suddenly recalls that he “was born on the Quinnipiac.” This latter recollection is a nice example of the kind of deeply personal, affective association a place can carry. His diary entries often telescope past and present like that, as observations give rise to recollections that in turn link themselves back to the present moment as it unfolds before him.

Connors is a careful observer of the local trees and birds, whether he’s looking at the catalpa trees on Nash Street, noting the slouch of bare elms at Lighthouse Point in December, or spotting an egret on Brazos Road near the East Haven shoreline. We can feel the seasons change through the details he relates—the smoggy, stagnant air and humid skies so characteristic of New Haven summers; the falling leaves in autumn; the early snow. The seasons in New Haven are distinctly affected by its location on Long Island Sound and its situation within Connecticut’s Central Valley; networked with wetlands and maple and oak woodlands, its summers are hot and sticky, its winters long and snowy, its autumns colorful, and its springs announced with an abundance of skunk cabbage.

If Connors’ diary entries capture the underfoot details of various locations in New Haven, his haiku seem less tethered to the characteristics and history of a city and more indicative of the generalities of time, as experienced through the seasons and the phenomena they give rise to. Winter, for example, is epitomized as

blackberries

under dawn sky

bittering

Summer is just as obliquely memorialized in

thunderclap

a morning moth

clings to me

Connors’ choice of haiku as a vehicle of expression is apt for someone attuned to seasonal phenomena. For the uninitiated reader, haiku pose a unique problem. Their ostensibly simple form and diction are in fact rich with conventions and allusions, both direct and indirect, that aren’t immediately apparent. A well-developed critical apparatus and long-standing interpretive tradition that have accrued in Japan and among serious non-Japanese haiku practitioners have been dedicated to elaborating this richness. Even so, haiku are intuitively legible as embodying what we might think of as a downward glance, a circumscribed “weak” or “soft” metaphysic of the particular that, letting things disclose themselves through direct language, reveals the deeper significances of the mundane and natural environments in which we are immersed. Such a “weak” metaphysic contrasts with the Ideal Form of New Haven’s Puritan founders as well as with the epistemic imagination of Stevens’ Professor Eucalyptus.

The “weak” metaphysic of the particular is just the other side of the “oneness of experience” that Connors and Langille, in their essay on the blues and haiku, assert is the expressive burden of haiku. The relationship between the two can be understood as consisting a movement of reciprocity in which the former is revealed through the latter, and vice versa. It’s consequently possible to read Connors’ haiku—as well as haiku generally—as a writing of correspondences in which the macrocosm is inscribed in miniature in the observed detail. The markers of seasonal change so prominent in haiku aren’t symbols but rather more like natural signs thrown off by the world in its flux and its finitude, the larger meaning of which is secreted in the heart of the seasons’ cyclical regeneration. These natural signs are a reminder that it is the ordinary things and landmarks that constitute the affective maps in terms of which we find our way in the world. Autumn’s Sun is just such a map, drawn by a skilled mapmaker.

Loren Connors

Autumn’s Sun

Blank Forms Editions→

◊

Daniel Barbiero is an improvising double bassist who composes graphic scores and writes on music, art and related subjects. He is a regular contributor to Avant Music News and Perfect Sound Forever. His latest releases include Fifteen Miniatures for Prepared Double Bass, Non-places with Cristiano Bocci & their most recent collaboration, Wooden Mirrors.