The World and Its Double

Daniel Barbiero

November 2017

Object and Shadow (The World and Its Double)

In his story “Tlön, Uqbar, Orbis Tertius,” Borges tells of a gnostic in the fictional country of Uqbar who proclaimed mirrors to be abominable, because of their seeming duplication of those who look in them. This gnostic’s anathematizing of mirrors reached beyond the atavistic fear of the doppelgänger to something more fundamental. What the Uqbar gnostic objected to was the mirror’s multiplication of the visible universe, a universe he considered a sophistic illusion. But the condemnation of the mirror’s multiplication of the world as image is already too late. Even before any mirror can come into play, the world as we exist in it already is something akin to an image of that which necessarily transcends it. And in its rejection of the reality of the physical universe, the gnostic’s revulsion turns out to be a variation on the ancient puzzle of the relationship between thing and idea.

The interplay of thing and idea, of object and shadow, is reciprocal, an equation subject to a reversal of terms depending on one’s metaphysics. In a Platonic universe the object is a shadow thrown by the Idea it imperfectly instantiates; in an Idealist universe the idea is the shadow by which we know the object. In either case it is the image that discloses the reality behind it. If we consider that our beliefs about and desires directed toward the world shape and are dependent on an image of the world, then we can read the prohibition against mirrors as a cautionary allegory warning against displacing the reality in favor of its image and of taking the image for the reality. This also allows us to identify the gnostic’s error in making the leap from positing physical reality as a secondary or derivative reality to denying it as a reality at all. In reality, our idea of the world pervades the world just as the world pervades our idea of it.

The implication of the opposition of Idea and object is that we are left with a second opposition: that between the infinite and the finite. The idea is the infinite, the shadow existing outside the limits of time and space; the object is the finite, an instance of real being determined by a given extension in time and space. The former is an abstract notion, the latter a contingent element encountered in the network of relationships in which we inevitably are implicated.

The Apeiron

The idea of the infinite haunts Western philosophy from its beginnings in Ionia. Anaximander of Miletus, the earliest Greek philosopher whose own words have come down to us, introduced the notion of the infinite as an explanatory element in his account of the cosmos. In his single surviving fragment, he speculates that all things ultimately derived from τὸ ἄπειρον–the apeiron, an infinite, limitless and inexhaustible ground of being. In the Physics, Aristotle concluded that Anaximander’s apeiron was a boundless source from which beings derive, a beginning of things that itself has no beginning or end.

The apeiron, as the concept of the open and unlimited, is important because it places itself in opposition to the sense of finitude that pervades human being. It apparently was meant to solve the problem of accounting for where beings originate—of how the supply of individual beings, each of which is perishable, itself is imperishable. As such, it was a response—a metaphysical, and not necessarily existential response–to the reality of limit that each of us has to live, and to the contradictory tension between the one-way course of any given life and the encompassing life cycle within which it is an element. In a way, the apeiron represents a way of overcoming finitude with an image of its opposite.

From the perspective of concrete human existence, the apeiron doesn’t epitomize life but instead represents an exception to it. To that extent, the apeiron is an idea that embodies the opposition of Idea and object as it presents the image of a world quite different from, and in some respects higher than, the world as it really is. A world as unlike ours as it is unlikely.

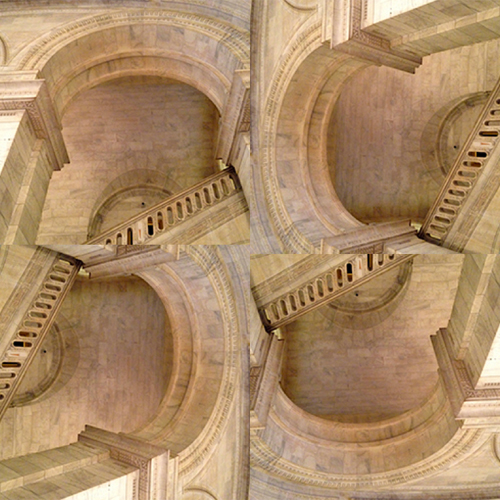

Implicit in the image the apeiron presents is the neutralization of time. The apeiron is the consummately synchronous state of having all things present and present to each other simultaneously. As an analogy, one thinks of a vertical structure in music—the co-occurrence of pitches forming a harmony—or of a building jumbling period styles in one solid mass.

In a stroke of irony, the infinite implies finitude, in spite of itself. Its openness implies the possibility that the future we endeavor to bring about may not happen; that the fixed track of necessity stretching ahead of us and carrying us forward on a preordained path is an illusion. The infinite means infinite possibilities, one of which is the paradoxical possibility that certain possibilities will not be realized. When considered in this way—as a set of concrete possibilities—the idea of the infinite appears to refute itself. As with Russell’s paradox, all the possibilities we can conceive of include the possibility that none of these possibilities are possible. Even in realizing one possibility, we negate the other possibilities our realized possibility prevents from coming into being. A world structured by possibility carries negation within it as a constituent element.

Negation

When we take a stance of negation in the face of a world structured by possibility, negation goes beyond the individual gesture and serves as a metaphysic, that is to say, as a ground on which we base our being. There are two moments of negation in this metaphysical sense: The negation that we are by virtue of our not being the world outside of us, and the negation of the world that we imagine in projecting a desired future state of affairs. The first kind of negation is negation as difference; the second kind is negation of the given in favor of a desired state of affairs.

Like the notion of the infinite, the expression of difference in terms of negation reaches far back—probably as far back as analogical thinking, in relation to which difference is a complementary opposite, a kind of anti-analogical way of thinking. (Imagine an inversion of the old Hermetic formula “As Above, So Below” as: Below is what it is by virtue of its not being above.)

Some early commentators saw negation as difference implicit in Anaximander’s fragment. On this reading, it was through the negation of difference that individual things arose within the apeiron. Specific qualities were thought to emerge from the undifferentiated whole when its unbounded being was differentiated into opposites–qualities emerged when one thing could be known for what it is by virtue of its not being something else. Negation as difference has also been expressed in terms of non-being. The Eleatic Stranger in Plato’s Sophist argued that non-being was another way of naming difference—A’s non-being is A’s not being B. Non-being in this sense isn’t nonexistence or the absence of being, but rather negation in its creative aspect: to negate this by recognizing it as not-that is in a sense to create it as what it is and nothing else. Being, in other words, takes on definite characteristics through non-being, that is, through negation as a metaphysical move which yields the insight that something is what it is by virtue of what it is not. Through difference, things make themselves known by virtue of what they are not.

If through the differentiation of the infinite finite things arise, then finitude grasps itself within the infinite. But the infinite cannot grasp itself in finitude—except as the negation of the concrete life in favor of the generalized notion of a life cycle. A concrete life is left with its finitude, and consequently is directed out beyond itself in desire.

Desire and Lack

In attempting to realize ourselves in the world, we negate the world through desire. (To desire in this instance just means to want.) Desire, which is the projected image of what we lack or need, ties us to ourselves just as it ties us to the world. What we need is to be found in the world, which can satisfy the physical needs associated with survival, such as food and shelter, as well as the emotional needs that are met through the various modes of coexistence with others, and the non-essential desires the fulfillment of which are means for attaining status (which itself is a quality of coexistence). If we are defined as much by what we are not as by what we are, then desire arises in between the two to try to close the gap between them and to make good what it is we lack. To that extent, need is the possibility of opening out to the world, of grounding ourselves in a relationship to the world that discloses ourselves to ourselves as something more than, and at the same time less than, that world.

From the perspective of need, the world is a plenitude, a surfeit of the being that we understand ourselves not to have. Our lack pushes us out into a world whose plenitude provides us with our only recourse toward making good our need; thus desire is essentially outward-directing and enmeshes us in a world of things, situations, and above all, others. To the vaguely Platonic notion that the object is a shadow cast by its Idea, we can counterpose the idea that desire is the shadow thrown over the object by human finitude.

Desire is a projection of a state of affairs other than what currently is the case with the world; it negates the actual in the name of the possible. Thus negation is just another perspective on the world, a perspective that comes into being through possibility. In order to grasp the world as harboring possibility, indeed, as made up of possibilities rather than a fixed, deterministic course, we must be able to imagine its negation and supercession by something other than what it is at any given moment. To negate in this sense simply means to imagine something else.

We project out into the world in the name of a future that this present moment links to the past that we were; it is on the basis of that past and what we’ve derived from it that we envision the future as a concrete possibility for ourselves. To grasp the world as a situation presenting certain possibilities isn’t to represent it as an image so much as it is to perform an operation on it: to project a new situation, on the basis of the given, that may or may not be realized. The world as given is from this point of view a single moment of the present ranged against our projected unity of past and future; our ability to project a future represents our ability to transcend and overcome the world in the name of the future we project.

Possibility is inevitably negation; the future we project negates the world we are given. Through need and the desire that arises from it, our relationship to the world is in the Eleatic Stranger’s sense a relation of non-being. We are our future in the manner of moving toward it but not yet being it; to that extent, we and the world are mutually transcendent, implicated in an intricate, reciprocal movement of approach and withdrawal. Any unity between ourselves and the world is perpetually pushed off into a possible future—one that may or may not come to be realized. It is here, in the perpetual deferment of our unity with the world, that freedom comes into play. The choice we make of the future is free to the extent that it isn’t inevitable; freedom inheres in fidelity to the act of choosing a real possibility rather than to the successful achievement of a desired end. We have an appointment to meet ourselves in the future, to shake hands with what we have to be by the shadow of a tower that embodies the solid mass of the world as it is. But there is no guarantee that the appointment will be kept.

Which brings us back to the infinite. The role of the infinite is not to signify real possibility but something we may be drawn toward in addressing our own finitude. When this is the case, desire becomes in some very general sense a nostalgia for the infinite—a longing to return to someplace we’ve never been and never could reach. The infinite is the negative counter-image of what is actually possible and thus is always beyond us, receding even as we approach it.

In its recognition of finitude—of its acceptance that real possibility isn’t infinite possibility–desire is the other side of freedom, if the latter consists in the choices we make in reading our desires in light of our real possibilities. (Thus in a neat reversal of Anaximander’s speculation, it is the finite that is the ground of human being.)

Object and Sign (The World as Our Double)

Through desire and its projection of a possible future, the object—the object of desire, the object as a means to obtain what is desired—the object, in short, as a kind of surrogate for the world at large–is changed. It is stripped of its status as thing, as an inert instance of matter and instead becomes a node in a network of meanings: it is transformed from an opacity to a sign and is now something to be interpreted as well as to be gained or used or, better, something to be interpreted as needed or useful. The desired object or the object that plays an instrumental part in realizing that desire is the object imbued with meaning; it is as much a sign as a thing in the world. What it signifies is the concrete possibility of filling a lack; to that extent it is meaning stamped on being by non-being.

Likewise, seen in the light of possibility, the world isn’t a collection of contiguous, discrete objects so much as it a system of relationships, a signifying network of attractions and repulsions, of consonances and dissonances. Possibility organizes and structures a world and its constituents in terms of how they fit into our projects, how they can make good our needs, what their implications are for our capacity to desire and to attempt to realize our desires. The world thus understood is an evolving network of meaningful relationships given weight and priority by our involvement in them.

Within this network there is neither object nor shadow, but simply a subsuming understanding; not an abstract idea but a relationship of significance rooted in the concrete exigencies of our own existence. Because it is in the context of existence that these signs operate—existence as a mode of being proper to us as self-conscious, finite beings whose futures aren’t fixed and who consequently must realize ourselves through the possibilities available to us in the concrete situations in which we find ourselves. Existence makes itself known through these signs, which are intelligible within a world structured on the one hand by lack and on the other by possibility. The network of meaning that enmeshes both is a kind of middle term in which each participates and through which they know each other by mutual illumination. Through these signs the world becomes our double—not as a solipsistic projection or as the needless multiplication of entities that repelled Uqbar’s gnostic, but as a confluence of what we are and what we are not, as we move toward what it is possible for us to be.

Images by Randee Silv