The Letters of What Is Not

Daniel Barbiero

July 2022

All images courtesy of the artist

All images courtesy of the artist

Signification is a deeply rooted human instinct, an instinct as natural as any other. It encompasses not only the creation of signs but the interpretation of signs and by extension, interpreting as signs marks, objects, and events that carry no pregiven, intended meaning. The human instinct is to see meaning, and to create it when none exists. Asemic writing—writing or writing-like marks whose forms hint at signification, but which carry no intrinsic or intended semantic content—draws its fascination from this instinct, as it plays on the unbridgeable gap it deliberately opens up between form and meaning. We see something that looks like language and instinctively try to decipher its meaning. We may not succeed, but we want to see it as meaningful nonetheless. But if the “language” is deliberately asemic, we are confronted with a semantic field that is barren by design: a situation where form is emptiness, and emptiness is a provocation to interpret. We tend to abhor a vacuum of meaning and want to find it, even if it means taking a hermeneutic leap of faith.

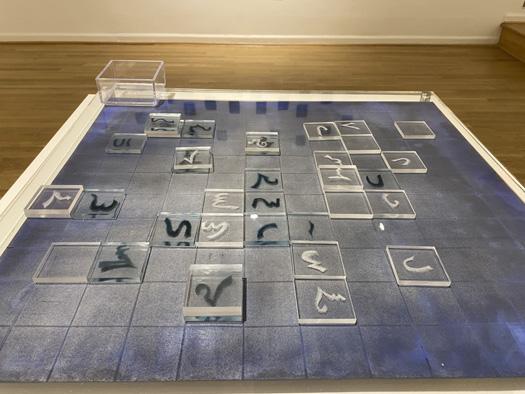

Much work labeled as asemic writing is hermeneutically provocative at the level of the text. With her work Postscript Letter Bank, artist Kate Fitzpatrick provokes questions about the implications of non-signifying signifiers at the more basic level of the letter. The work consists of a board and a set of clear acrylic tiles, each of which carries a blue or white mark evocative of a grapheme in the form of a cursive letter from an unknown alphabet. Some of the marks look like Arabic letters or Japanese Hiragana characters; in fact the tiles look like they could be pieces from a Shogi game developed in another possible world.

Postscript Letter Bank’s resemblance to a board game isn’t accidental. In fact, Fitzpatrick describes the work as exactly that–a game, but one in which the player can make up his or her own rules in order to assemble the tiles into meaningful forms. The tiles can be placed in any order on the board, which is divided into a grid of tile-sized squares; the player can arrange them any way he or she likes. One observer aptly likened it to a game of Scrabble. A player can set out tiles in sequences to create “words,” and as with an anagram, the “words’” “letters” can be rearranged into new combinations and presumably, new meanings. And yet despite its focus on meaning, Postscript Letter Bank is literally a nonsense game, since no matter how they’re arranged, none of the tiles can spell out words that carry sense in a way that words in an ordinary language carry sense. If a language game is a framework for using and understanding words by virtue of stable and conventionally understood rules for associating signs with sense, Postscript Letter Bank is a game for language that overturns the very idea of a language game.

Postscript Letter Bank is one of a number of asemic works in There Is No Anagram for Anagram, Fitzpatrick’s show at the Hillyer Gallery this month. Fitzpatrick has a history of creating artworks alluding to writing systems, going back to her Asemic Manuscript, shown at George Mason University’s Fenwick Gallery in 2018, and her 2020 MFA thesis work Liminal Glyphs, also shown at GMU. The marks on Postscript Letter Bank’s tiles bear a family resemblance to some of the glyphs on this latter work, which consists of a screen of white script-like forms cascading onto the floor in front of a curtain of black paper. Postscript Letter Bank takes Liminal Glyphs’ idea one step further by breaking the lines and curves into separate units and isolating each one as a discrete grapheme that can be put into combination with the others.

If Postscript Letter Bank resembles Scrabble, it’s a variety of Scrabble played with pieces whose values necessarily are empty variables. Scrabble tiles are ranked according to the rarity of the letters they contain; the rules of spelling and the frequency with which certain letters are needed to spell common or uncommon words underlies its system of ranking. The ambiguous way in which letters carry meaning—sometimes individually as morphemes, more generally as phonemes—is reflected in their rankings as well. By carrying no pre-given meanings, by representing no phonemes, Postscript Letter Bank’s marks seem to exist as graphemes stripped of signification and reduced to a visual residue.

If works resembling quasi-texts without intended meaning count as asemic writing, then quasi-graphemes without intended corresponding sounds count as aphonic letters—elements in an alphabet of silence. The silent alphabet is a seemingly purely visual alphabet, but its graphemes nevertheless point beyond themselves to an idea that escapes reduction to the purely visual. They are quasi-letters that derive their force from the fact that there are, if not here then somewhere else, real letters carrying real meaning. We interpret these non-letters as being letter-like against the practical background of actually existing letters—a background they bring, by accident or design, to the foreground. Works like Fitzpatrick’s, which hone asemic textuality down to its elemental constituents, help us to see again the grapheme for itself, as the material trace that it is. Against the background of literacy we tend to take graphemes for granted, seemingly looking through them to their sounds and/or senses on the ordinarily unexamined assumption that they are somehow transparent. (Similarly, we may unthinkingly assume that language is transparent in relation to the thoughts it expresses.) We tend to forget that alphabets are something like minor miracles of signification—simple artifacts that, through a system of orthographic and grammatical conventions, not only afford access to the complexities of the world, but provide the elements with which those complexities can be fixed and conveyed. The silent letters of invented alphabets, in separating the formal, material traces of the signifier from the sounds and senses it serves to signify, help to remind us of this.

Still, we want things to make sense, especially when those things are signs or sign-like things. We want them to, even when they carry no fixed or pre-given sense. The desire to interpret them as signifying something is virtually a reflex that can’t be helped. Postscript Letter Bank’s design as a game is predicated on this reflex. When the artist invites potential players with the question, “How can these signs make meaning?” she anticipates the question that might arise spontaneously in the viewer. To play the game is to invent a language, to systematize a relationship between the blue and white marks and a corresponding set of referents. The tiles’ lack of pre-given meaning is only an opening gambit; their non-sense represents a lack that carries with it the possibility of sense.

Plato hypothesized a set of geometric elements he called letters—stoicheia–as the building blocks of the material world. Call them the letters of what is. Set free from the function of signifying sound or sense, Fitzpatrick’s quasi-graphemes are the letters of what is not. But by playing the hermeneutic game she invites us to play, we can apprehend them as the letters of what might be.

Kate Fitzpatrick

There is no anagram for the word anagram

July 2 -July 31

Hillyer Gallery

Washington D.C.

website →

Kate Fitzpatrick’s website →