The Anti-Metaphysical Metaphysician

Daniel Barbiero

October 2019

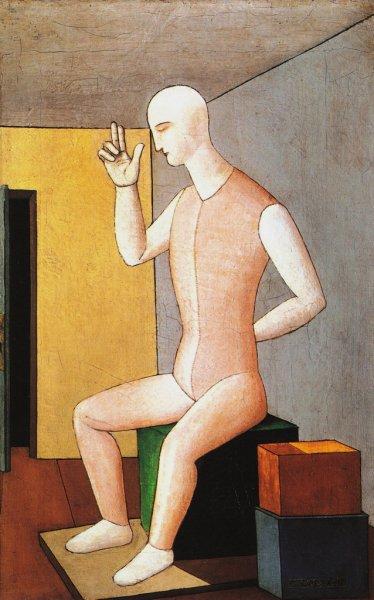

L’idolo ermafrodita, 1917

L’idolo ermafrodita, 1917

The School That Was Not a School

January, 1917. Italy was entering the third year of its involvement in the First World War. The Piedmontese painter Carlo Carrà, now a soldier in the Italian army’s 27th Infantry Regiment, was stationed in Pieve di Cento, outside of Ferrara. Corporal Giorgio de Chirico, also of the 27th Infantry, was already in Ferrara, working as a clerk at the army depot there. De Chirico had been in Ferrara not long after having returned to Italy from Paris in 1915 for army service. Ferrara, as it turned out, was the locus of a powerful convergence of artistic forces, and one that coincided with a significant turning point in Carrà’s art.

Sometime in March, 1917, Carrà met de Chirico and de Chirico’s brother Alberto Savinio. This had happened after he had initiated correspondence with them on the recommendation of journalist Giovanni Papini. In early April, both Carrà and de Chirico were sent to the army’s neurological hospital in the Villa del Seminario outside of Ferrara, where they stayed until mid-August. There they painted, encouraged by the facility’s director, and formed a close but short-lived partnership.

The Villa del Seminario collaboration was the core of the so-called scuola metafisica—the group of painters who took inspiration from de Chirico’s Ferrarese paintings. In addition to de Chirico and Carrà, these painters included Giorgio Morandi and Filippo de Pisis. It was a short-lived school that wasn’t really a school at all; as Giuliano Briganti points out, there was no program, no manifesto or other collective statement of purpose to define or constrain it. These were different artists with different goals but with some commonalities, among them an interest in exploring the plastic and atmospheric possibilities of depicting interior spaces containing certain kinds of objects in strange combinations.

Carrà’s direct involvement with de Chirico was especially brief. He left Villa del Seminario on leave in mid-August, 1917 and shortly thereafter was honorably discharged from the army. He returned to Milan, where in December he organized an exhibition of his new paintings; de Chirico, under the impression that the show would include paintings of his own, sent Carrà three canvases, which were not included. By early 1918 the two had fallen out over what the de Chirico scholar Paolo Baldacci characterizes as Carrà’s betrayal of de Chirico. While Carrà maintained that de Chirico sent his work too late to be included, Baldacci’s own research into contemporary postmarked documents establishes that that wasn’t the case. Either way, the collaboration, and friendly relations, between the two painters was over.

It may have been that Carrà’s metaphysical period simply represented a transition for him. Since 1910, he had been a Futurist painter but by 1914 was becoming disillusioned with the movement generally and with its leader F. T. Marinetti and fellow painter Umberto Boccioni in particular. Although he continued to sign his paintings as a Futurist through 1917, he’d grown dissatisfied with the Futurist preoccupation with constant motion and disruption and was looking for what he hoped would be a way to engage the world more deeply. For this, he felt he needed a formal language different from Futurism’s fragmentary, multiplied figures. He was looking to the Italian old masters for a new direction, publishing essays on Giotto and Uccello in the art journal La Voce in 1916. (And in doing so pulling off a double negation: negation of the Futurist negation of the past.) His paintings, inspired by their art and the art of the Trecento, began to take on a simpler, quasi-primitive style with a deliberate coarseness or ugliness that the title of one 1916 painting seemed to sum up: Anti-grazioso, or “anti-graceful.”

If the art of the Trecento provided one model for Carrà’s turn away from Futurism, de Chirico’s painting provided another. Carrà may first have seen de Chirico’s paintings during a trip to Paris with Papini and his fellow critic and art journalist Ardengo Soffici in spring, 1914. It’s also possible that he saw several photographs of de Chirico’s work in 1916. Paolo Fossati describes Carrà’s early reaction to de Chirico’s pictures as “perplexed;” Baldacci reports that in a February, 1917 letter to Soffici Carrà remarked on what struck him as the “cold, literary rationalization” of de Chirico’s work. But he would soon find these perplexing pictures by the younger, relatively less-established painter—de Chirico, who was then virtually unknown in Italy, would be 29 in 1917, while Carrà would be 36—to be an inspiration.

Given the situation in which Carrà found himself when he formed his alliance with de Chirico, it’s fair to ask how committed he actually was to the metaphysical aesthetic and outlook. Baldacci, for his part, sees the scuola metafisica as something of a fiction and Carrà’s part in particular to have been an opportunistic move. And at one level it does seem that much of Carrà’s Ferrarese work is strikingly like one person trying to speak in another’s dialect. The iconography and even some of the compositional structures are often directly borrowed from the work de Chirico had been producing since 1915. At another level, though, Carrà does seem to have been searching for a visual poetics that would let him convey what he saw as a deeper reality. And as it happened, his idea of what constituted metaphysics differed from de Chirico’s.

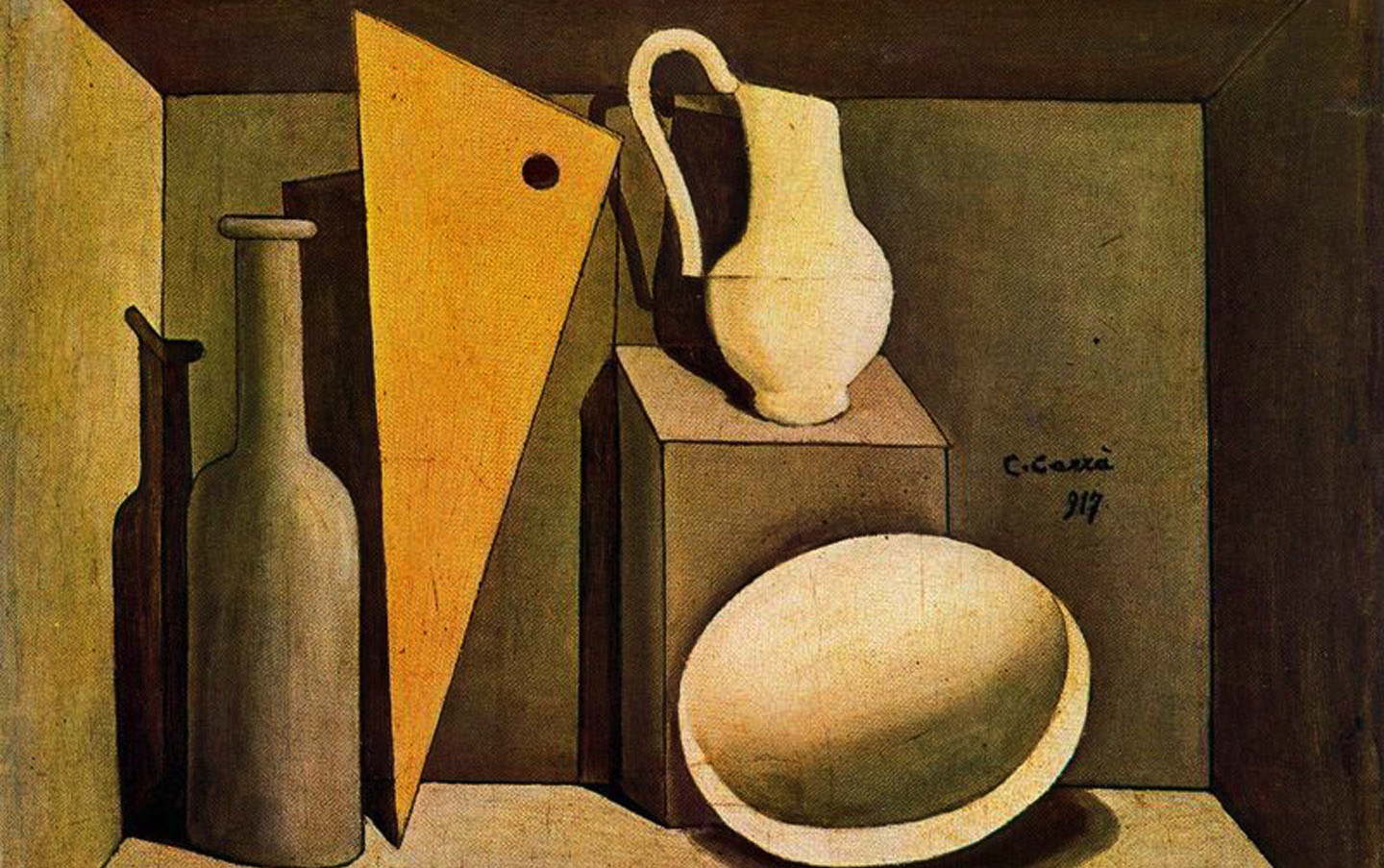

Natura morta con la squadra, 1917

Natura morta con la squadra, 1917

The Metaphysics of the Ordinary

In the catalogue to his December, 1917 show in Milan, Carrà described his art as deriving from a metaphysical vision. Statements he composed in 1918 which were collected and published in the book Pittura metafisica in 1919 introduced and developed his notion of what metaphysical painting was concerned with and how it could create its effects. What these statements demonstrate isn’t that Carrà never really was the metaphysician he claimed to be but rather that he was a somewhat paradoxical one–a peculiar kind of anti-metaphysical metaphysician who looked at things precisely as things.

Carrà’s attitude toward things qua things is clearly articulated in a 1918 statement titled Della ‘cose ordinarie’–“Of ‘Ordinary Things.’” With it, Carrà set out a program that neatly summed up the anti-metaphysical metaphysics of the Ferrara period.

In his statement, Carrà posited ordinary things as serving as both an artistic anchor and a fundamental way of orienting oneself in the world, warning that to abandon them is to “collapse into the absurd, and thus into nothingness whether plastically or spiritually.” For Carrà it was ordinary things that “reveal that form of simplicity that speaks to us of a superior state of being, which constitutes the splendid secret of art.” Ordinary things may be ordinary, but their effect, for Carrà, was anything but; it’s worth noting that throughout the statement the phrase “ordinary things” always appears in quotation marks, as if to call attention to the ironic fact that they aren’t all that ordinary after all, their appearances and our being habituated to them to the contrary. It is here, if anywhere, that the metaphysical dimension to Carrà’s artistic vision discloses itself. But because it is so rooted in the plain forms of the mundane and the material, it is a metaphysics that reveals itself through an ontological predisposition for the concrete that, in its validation of actually existing things, can only be termed anti-metaphysical. True, the “superior state of being” hinted at by the simple forms of ordinary things might possibly be identified with the hypothetical, and paradigmatically metaphysical, Platonic realm of pure form, but for Carrà access to that realm, if indeed that was what he had in mind, could only be had by way of material things.

If Carrà concerned himself with ordinary things, he did not take a stance toward them that would reduce them to their ordinary uses. On the contrary, that he was trying to show things apart from their uses is made explicit in the disdain he displayed, in “Of ‘Ordinary Things,’” for those “primitive natures” whose “puerile” sense of values leads them to approach ordinary things only in terms of their “immediate utility.” He was after a poetic effect—not the “false dream of the marvelous,” which he thought fit only for “vulgar and common natures,” but something quiet and austere. He wanted to penetrate through to “the hidden intimacy of ‘ordinary things,’” which normally goes unnoticed in the everyday lifeworld of activity and striving. It was Carrà’s intuition that we can only see this occulted side of things once we divorce them from their utility or instrumentality, and depict them simply and in a clearly delineated space.

Discrete Objects

Carrà’s intuition is clearly embodied in his metaphysical paintings, which give evidence of a formal language and conceptual underpinning representing something analogous to what Husserl described as going back to the things themselves.

Carrà’s anti-metaphysical metaphysics is epitomized by the Natura morta con la squadra of 1917, an undoubted masterpiece from his Ferrara period. The painting is remarkable for its formal clarity and balanced composition. Carrà depicts five simple objects: a bottle, a set-square, a jug or pitcher on a slant-topped plinth, and a strange, egg-like object with a rim or raised edge—in a kind of cube or tiny room open to view at the front. The colors are muted—grey, matte white, olive green, ochre. The objects’ edges are sharply delineated, as are the shadows they throw against the walls surrounding them.

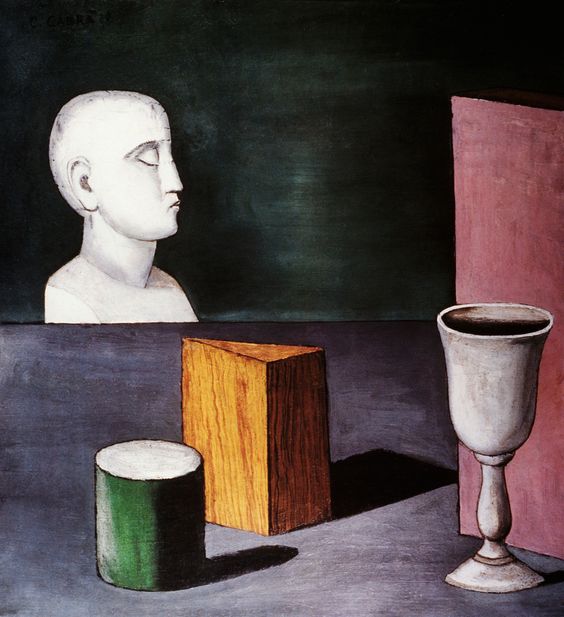

Each thing within the interior is shown as a discrete entity, as something well-defined in what it is. The set-square is plainly the object that it is, an instrument taken from a world of instrumentalities. Likewise the bottle and pitcher. As Carrà rendered them, all of these things are simple solids with plain surfaces, unitary objects that, taken individually, are like scaled-down minimalist sculptures in that they lack complex internal relationships between parts or between part and whole. They are wholes without parts. Even with its handle, the pitcher seems to have been made from a single chunk of matter; the empty space enclosed by the eye in the set-square doesn’t take away from that object’s integrity as a unitary thing. This strategy of taking simple forms and endowing them with solidity and volume was central to Carrà’s practice at the time and was taken even further with the 1919 Natura morta metafisica, a painting of a room sparsely populated by the simple solids of a cylinder, a three-dimensional wedge and a cube in addition to a goblet and sculpture of a child’s head.

.

Natura morta metafisica, 1919

Natura morta metafisica, 1919

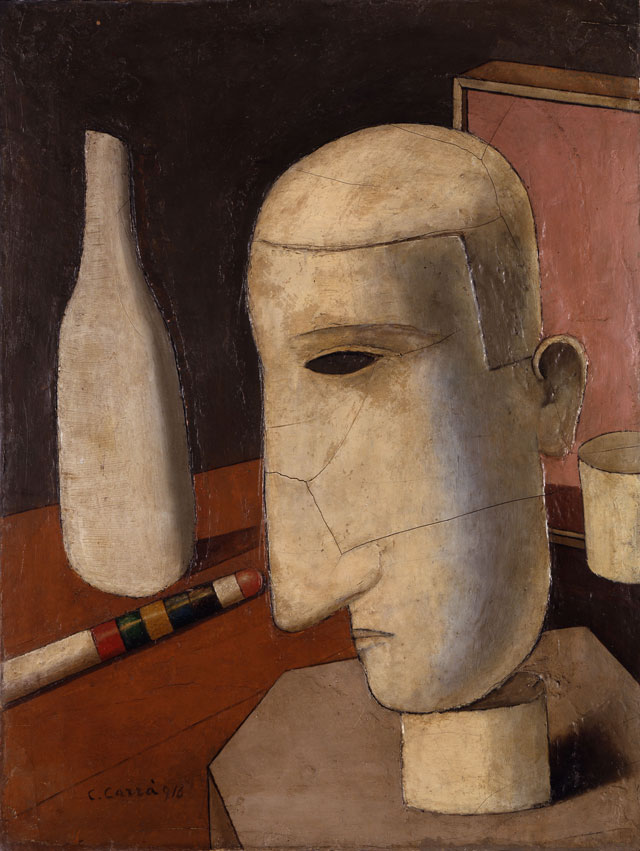

Paintings such as the Natura morta con la squadra display the formal means Carrà devised for provoking the move from the mundane to the metaphysical. The well-defined, paratactical relationships he used to structure his arrangements of objects isolated them and offered them up as self-contained things divorced from any necessary relationship to each other. The Gentiluomo ubriaco (“drunken gentleman”) of 1916 is exemplary in this regard. Set out on a surface within a darkened space are: a bottle; a striped baton; a white mask or sculpted head teetering on a cylindrical stand; a cup bisected by the right edge of the canvas. Like the objects in the Natura morta con la squadra, the objects here are holistically simple. Each of them holds to its own space without regard to the others; as entirely discrete entities, they have little communication with each other. Their mutual isolation is palpable, and is an essential element of the painting’s composition.

If the individual objects in this and in the other paintings of 1916-1919 lack any real internal relationships, the relationships that do define them are purely external. Carrà’s composition arranges them in such a way that they form a network of juxtapositions—a parataxis of adjacency without involvement. Unlike de Chirico’s metaphysical interiors, which typically contain a clutter of closely massed, overlapping forms, Carrà’s compositions contain objects whose surfaces and edges seem to be absolute boundaries enforcing a strict isolation. Each thing inhabits a space of its own, simply and tangibly. In effect, this isolation, simplicity and tangibility, taken together, served as the fulcrum on which Carrà’s metaphysical paintings balanced.

Things Without Alibis

Everyday objects, such as those Carrà painted, have a central if often unreflected-on role in the lifeworld each of us inhabits. Our existence is reflected back to us in the things that potentially play a part in that existence: as tools, obstacles, ornaments, and so forth. Human existence is to a significant extent lack; these ordinary objects are emblems of the necessary measures needed to negotiate our everyday lifeworld and its resistances, and somehow to make good that lack. But as we’ve seen, Carrà’s formal treatment of these objects removes them from that everyday lifeworld. In effect, he displaces them. Consequently, the world Carrà’s “ordinary things” inhabit is an atopia, a place where things are displaced and consequently left stranded and out of place. Getting from the everyday lifeworld to the atopia of the metaphysical interior is a matter of substituting a different perspective for the perspective of the everyday. It involves a way of seeing these things by virtue of their formal relationships rather than their given functions.

The perspective that Carrá opens up on his “ordinary things” is functionally equivalent to one that the Russian literary theorist Viktor Shklovsky termed ostranenie—alienation, or estrangement. As a literary device, ostranenie involves the wrenching of words or verbal images out of their ordinary context in order to reveal them in a new and extraordinary light. Transposed from language to painting, ostranenie consists in depicting ordinary things in extraordinary combinations or settings—as, for example, through the kind of parataxis and isolation Carrà used to structure his metaphysical interiors and still life paintings. With those devices Carrá created his particular sense of ostranenie by disrupting the relationship between the object and the everyday lifeworld—the world of action, of projects and the various pursuits of human interests and desires. He accomplished this when he freed the object from its function and submitted it to perception on the basis of its being as a brute physical fact—as mute surface, volume, and form. That is, as a thing in all its contingent existence, in its standing out from the background of the everyday as an unjustified and possibly unjustifiable knot of matter. By making them stand out so plainly, Carrá brought his objects out into the light of the unfamiliar, throwing them into a high relief where they can’t be ignored or taken for granted as instrumentalities. Rather than being shaded in the atmosphere of enigma—to use one of de Chirico’s most favored terms—they are instead disclosed in their banality and existential awkwardness.

The contrast with de Chirico’s metaphysical interiors, and by extension with de Chirico’s concept of metaphysical painting, is illuminating. De Chirico’s interiors are visual puzzles cluttered with strange or ambiguous things whose shapes obscure each other and whose identity is often indeterminate. De Chirico’s collection of objects–mannequins, architect’s tools, biscuits, maps or pictures on easels, partial picture frames, fish and fragments of whatever else—cluster in a knot of relationships whose meaning we can only guess at. The strangeness of it all hints at an esoteric significance derived from a personal mythology: inanimate things become oracles transmitting an all but indecipherable message. Whereas despite formal simplifications, with Carrá we always know what it is we’re looking at—a set-square; a pitcher; a bottle; a cube, cylinder or wedge; a statue head. A thing standing against us in its thingness. The message here is plain: the isolation and sheer being-there of these things bears witness to the contingency of their existence. To that extent they are things without alibis. For de Chirico’s things, by contrast, their enigma is their alibi.

De Chirico’s metaphysical interiors are Delphic where Carrà’s are atopian. That at least is the logical culmination of the estrangement he works on them, both by isolating them and by reducing their forms to a plain geometry. This simplification and isolation limit our perspective on them, but limit is the beginning of meaning: the reduced and displaced figure is, as Carrà put it in his 1918 statement “Metaphysical Painting,” “an image of the form so brightly lit that it arrests reality itself.”

What Carrà’s best metaphysical paintings reveal, then, is that the “hidden intimacy” of things consists in their pure thingness: in the sheer accident of their existing at all. Remove its immediate utility—separate it from its readiness to submit to our use–and we are compelled to confront the object qua object as something existing with a mode of being of its own. Carrà may not have intended to arrange this confrontation—or at least not a confrontation with this outcome–but his depiction of the objects in his metaphysical paintings bring it about not only by isolating these things from their functions, but by thrusting them out toward us in plain sight, as so many opacities erupting into our field of vision. Strip them of their functional content in this way and they are returned to the brute fact of their particular existence. The fullness of their three-dimensionality—the volume and solidity that Carrà was concerned above all to capture, and did so successfully with his metaphysical paintings—becomes an index of their radical contingency and a visual sign of the purely accidental nature of their being here. Call it the ontological scandal of there being something rather than nothing. This is what the object in its isolation tells of itself—the gratuitousness of its existing here, now, in this form and not in another: the gratuitousness of its existing at all. It turns out that it is their radical contingency that constitutes the intimate secret of ordinary things.

Gentiluomo Ubriaco, 1916

Gentiluomo Ubriaco, 1916

Works Consulted:

Paolo Baldacci, tr. Jeffrey Jennings, De Chirico: The Metaphysical Period 1888-1919 (Boston: Bulfinch Press, 1997).

Paolo Fossati, La “pittura metafisica” (Torino: Einaudi, 1988).

Piero Bigongiari, presentazione, L’opera complete di Carrà dal futurism alla metafisica e al realismo mitico 1910-1930 (Milano: Rizzoli Editore, 1970).

Guiliano Briganti e Ester Coen eds., La Pittura metafisica (Venizia: Neri Pozza Editore, 1979).

Massimo Carrà, ed.; Caroline Tisdall, translator, Metaphysical Art (New York: Praeger, 1971).

Viktor Shklovsky, Bowstring: On the Dissimilarity of the Similar, Shushan Avagyan, translator (Champaign, IL: Dalkey Archive Press, 2011).

◊

Daniel Barbiero is an improvising double bassist who composes graphic scores and writes on music, art and related subjects. He is a regular contributor to Avant Music News and Perfect Sound Forever. His latest releases include Fifteen Miniatures for Prepared Double Bass, Non-places with Cristiano Bocci & their most recent collaboration, Wooden Mirrors.