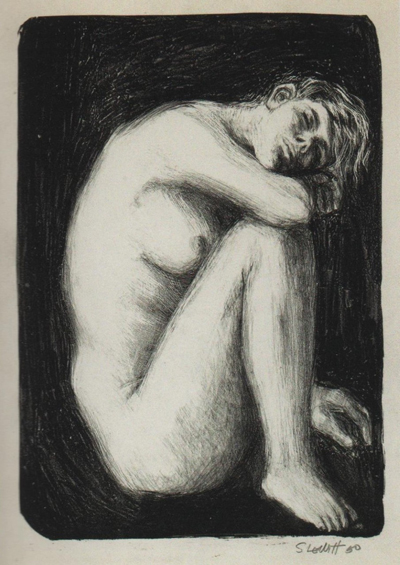

From the very beginning, LeWitt was fashioning his hand to make delicate and expressive strokes as demonstrated in the first lithographs and etchings dating from as early as 1948. Correlating the similarities between the first few prints in the exhibition and those that become identified with his signature language points to his awareness of the surface area on which an image would rest.

Strict Beauty: Sol LeWitt Prints Out His Vision

Lyn Horton

April 2022

Viewers must be visually cautious in approaching the art, no matter in what form, of Sol LeWitt as if it were for the first time, without preconceptions. The breadth of his work seemingly has no bounds. The work gives the impression of being restrained and constricted by rules yet the human element penetrates it with grace, boldness and tenderness. LeWitt knew this. The necessary parameters are always stated and evident but he created them with potentially unexpected results in mind. His story is told by drawn lines; strong, steady or wavering brushstrokes; and by the choices he made determining geometric design strategies in series of multiples, (even as pertains to his three-dimensional work).

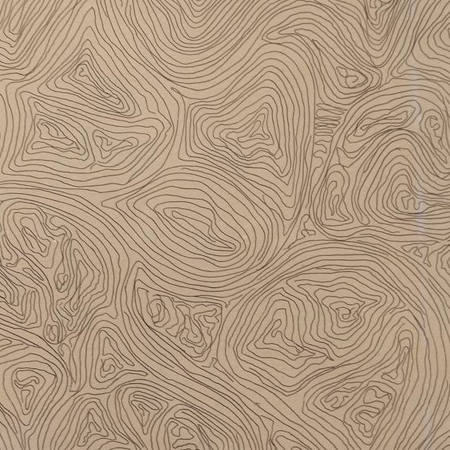

One of LeWitt’s many purposes was to map the surface in shaping any of his two-dimensional work. Throughout his history, he laid out the ways in which he would do that. In every level of engagement though, he allowed himself ways to move further. His vocabulary grew. His language evolved multi-directionally. Lines were the predominate informants. The lines started to form shapes; the shapes became filled with color. The number of choices he could make grew, as he developed layers and layers of givens which he could move around any way he wanted to without sacrificing the consistency of imagery. Printmaking no doubt gave him a range of subtleties that were unachievable in original work because he could move entire images that lived on plates and reincorporate them into the print which he was making or repeat images without the direct introduction of his hand.

The magnificent array of prints in Strict Beauty demonstrates a means with which LeWitt could magnify the richness of possibilities within a surface of paper. Because he was his own kind of perfectionist, nearly all of the prints appear as though they are original drawings. That is one reason that they are stunning, arresting and embracing, defying all attachment to a mechanized method of production.

LeWitt’s specific types of imagery appear and reappear but from different perspectives, with different nuances, in different colors, with different kinds of lines. Isometric geometry often forms the skeleton for the application of color or line or both.

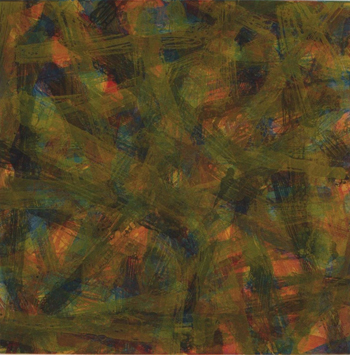

Fine lines become opaque brushstrokes, elegantly sweeping across the page over and over again in a sensical way, e.g. Parallel Curves, Wavy Lines, or in freeform combination of strokes, i.e. loops and curves, the fun-filled Loopy-Doopy; or move vertically in simple downward and upward strokes, overlapping, mixing with each other transparently in a gauzy curtain with an imaginary breeze wafting through.

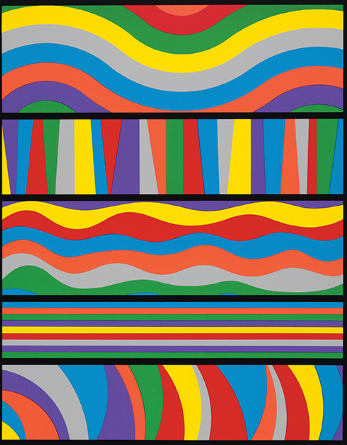

The expansion of surface takes place also with his use of color, persistently primary and secondary and combinations thereof, sometimes so muted it almost disappears and is visible only in contrast to another color or to black, and sometimes so brash and loud that the viewer can only approach the piece from a certain distance in order to absorb it, i.e. The Lincoln Center Print, 1998.

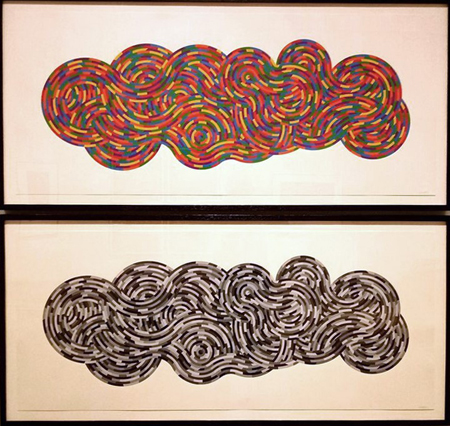

Whirls and Twirls, Color, and Black, 2005, were made two years before LeWitt passed away. They are a magnificent journey of primary color, geometry and free flowing guided lines all contained within one fundamentally curvilinear shape. These pieces were double-hung as the conclusion of the exhibit. They express the unceasing dynamic that energizes LeWitt’s work.

Art grows from innumerable sources. Those sources are instilled in an active artist’s creative being and stem from life experience, education, consciousness and basic knowhow. The results of an artist’s process are seldom as definably pristine as the way in which LeWitt’s unfolds. But indefatigable analysis from outside of an artist’s work that apparently invites it squeezes out any chance of its being appreciated for its essence which is to be beautiful, thoroughly beautiful.

Illustrations from top to bottom: Untitled (Female Nude), 1950, lithograph, sheet size 15 7/8″ x 11 9/16″; detail from a set of six Line Etchings, etching, color etching and aquatint, 2000, each sheet size 16″x 16″; Straight Brushstrokes in Five Colors in All Directions, 1996, color aquatint, sheet size 29″ x 29″; Six Brushstrokes in Different Colors in Two Directions, 1993, color sugar lift aquatint, each sheet and image size 47″ x 29 3/8″; Lincoln Center Print, 1998, screenprint, sheet size 38″ x 30 1/4″; Whirls and Twirls, Color and Black, 2005, color linocut, each sheet size 25″ x 55.”

(This article was written after seeing Strict Beauty: Sol LeWitt Prints, curated by David Areford, PhD, at the Williams College Museum of Art, Williamstown, MA. The exhibit was installed first at the New Britain Museum of American Art, New Britain, CT, where LeWitt’s work was first exhibited in 1949.)

Strict Beauty: Sol LeWitt Prints

February 18 – June 11, 2022

◊

Lyn Horton has been an artist for over fifty years. She has a long history of writing about creative improvised music for well-known publications, reviewing recordings, interviewing musicians and composing editorials. Her art has been exhibited widely and is represented by the Cross MacKenzie Gallery outside of Washington, D.C. Her website records her art and has a link to her writing blog. Her photographs can be seen on Instagram, and Water Journal: In Medias Res.