Remedios Varo’s “Tarot Card”

Daniel Barbiero

September 2024

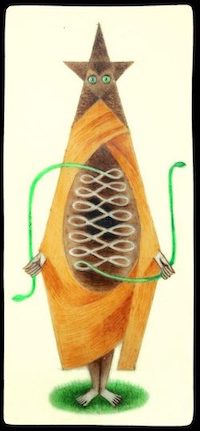

Remedios Varo, Carta de tarot (Tarot Card), 1957.

Remedios Varo, Carta de tarot (Tarot Card), 1957.

Oil on bone; 12 × 5.4 cm (4 3/4 × 2 1/8 in.)

Among the later works of the painter, sometime Surrealist, and esoteric visionary Remedios Varo is a mysterious painting of 1957 simply titled Tarot Card. The painting is a small – approximately two inches by five inches, about the size of a playing card – work of oil on bone. What makes it mysterious is the most basic fact about it: the identity of the card it portrays.

Varo’s composition is as simple as its title. Against an empty field of off-white a strange figure stands barefoot on a small patch of grass. He or she – the sex is indeterminate – faces the viewer in a full frontal stance. The figure is wrapped in a saffron-colored robe open from the chest to the abdomen, revealing a hollow interior inside of which is a looping or coiled line whose two ends lead out from the hollow and into his or her two outstretched hands. Each end terminates in a snake head. But the most prominent feature is the figure’s head: it is in the shape of a five-pointed star whose internal lines make it a proper pentagram. From the center of the star two wide-open eyes stare out at the viewer, as if the figure has been taken by surprise. The face is painted in a slightly lighter shade of brown than the surrounding areas and the forehead is framed by a widow’s peak; this, along with the visible brushstrokes on the start’s points, gives the impression that we are looking at the face of a hirsute animal of some sort.

Varo’s painting is mysterious because it doesn’t resemble any of the cards readily recognizable from the conventional 78-card tarot deck. (I take the 17th century Tarot de Marseille and its derivatives as setting the iconographic standards for the conventional deck. And as Decker and Dummett have shown, the 18th century French inventors of the occult tarot took it to be the traditional tarot deck as well.) Because the tarot’s trump suit traditionally has been the focus of attention for esotericists and cartomancers it’s natural to assume that Varo’s painting represents her reimagining of one of the tarot’s twenty-two trump cards. But which one? Cards in the trump suit ordinarily carry numbers by which they can be identified; Varo’s doesn’t. We have to turn instead to iconographic clues to try to solve the mystery of its identity.

Given the resemblance between the figure’s star-shaped head and the five-pointed star formed by the conical hat and pointed beard of the juggler depicted in Varo’s painting El malebarista o el juglar, Arcq et al. identify Tarot Card with trump card number one, variously called the Bagatto, le Bateleur, the Juggler, or in the English-speaking esoteric tradition, the Magician. While there is a general resemblance between the two figures the differences between them seem more significant. Unlike Varo’s juggler, the figure on Tarot Card wears no hat; while her juggler clearly is a human male the figure on Tarot Card is ambiguous and seems to represent some kind of imaginary or purely symbolic or allegorical entity with human features. I have doubts that the two can be identified with each other, although it is possible that Varo drew on the earlier painting when designing Tarot Card. In contrast to Arcq et al., the Argentine esotericist Julio Sánchez Baroni interprets Varo’s card as representing Temperance, the trump suit’s fourteenth card, which traditionally portrays a winged figure or angel pouring water between two jugs. Baroni’s interpretation is ingenious. He notes that the coils within the figure’s hollow torso sum to fourteen, and also finds a parallel between the two serpent heads, which he describes as “spouts,” and the Temperance card’s two jugs. He sees the Varo figure’s star-shaped head as corresponding to the five-petaled flower appearing on a headband the Temperance angel wears. Baroni is correct about the number of loops, and given Varo’s positioning of the figure’s hands and snake heads, it is possible to see a stylized representation of the Temperance angel’s handling of the two jugs. On the other hand the flower on the Temperance angel’s headband is a very minor ornamental detail and nowhere near as prominent as the star in Varo’s painting; consequently, I don’t think it can be considered the source of the latter. (The flower is a minor enough motif that on some variants of the Temperance card there is only a colored disc on the headband, not a flower with articulated petals.)

The interpretations offered by Arcq et al. and Baroni are to an extent plausible, if inconclusive. If we aren’t convinced that either the Bagatto or Temperance is the card Varo’s painting is meant to portray, which other card can we point to as a possible source? I want to suggest that Tarot Card lends itself to being interpreted as the Star card, number seventeen in the trump suit.

Admittedly, Varo’s card doesn’t look like the Star card from the Marseille deck or its offshoots – the card we ordinarily think of when we think of the Star. The main figure on the Marseille Star is a nude woman kneeling by a small body of water into which she pours the contents of two jugs. By contrast Varo’s figure is standing on a grassy patch and is clothed. The two serpent heads in Varo’s painting may be seen as stylized recastings of the two water jugs – similar to the way Baroni sees them as representing the two jugs on the Temperance card, which the Star resembles on this point. However, the strongest argument in favor of seeing Varo’s card as the Star is the simplest: its obvious focal point is the large five-pointed star that dominates its design.

That Varo’s card doesn’t follow the iconography of the Marseille Star isn’t necessarily evidence that it cannot be the Star. Since the tarot deck was invented in the mid-15th century the iconography of the Star underwent several changes and thus existed in a number of variants, some of them quite different from the Marseille type as well as from each other. For example, the hand-painted D’Este deck, probably produced in Ferrara around 1475, depicts two men pointing up at an eight-pointed star overhead. The one on the right holds a book or a chart, indicating that the men are meant to represent astronomers or astrologers. The theme of the astronomer or astrologer looking up at a star can also be found on the Star cards of some early French decks. The Tarot de Paris, a printed deck from around 1650, shows a seated man holding calipers as he appears to take a measurement of the large eight-pointed star above him. Similarly the Vieville deck, another mid-17th century printed deck from Paris, depicts an astronomer or astrologer seated outdoors in front of a tower as he holds a pair of calipers and looks up at a large star with rather shaggy looking rays. And then there is the Florentine minchiate deck, a 97-card relative of the tarot, whose Star card shows one of the three magi on horseback holding a cup or chalice and following a large, eight-pointed Star of Bethlehem. The figure on horseback beneath a large eight-pointed star turns up on the Star card of the Sicilian deck as well, where it is numbered sixteen rather than seventeen. And finally, there is the unusual Star card in the Bolognese deck, which like the Star card in the Sicilian deck is numbered sixteen. This card appears to portray a coronation scene in which a crowned man who may represent the Pope holds out a crown to the man in the middle, while a crowned man on the right looks on. Above them is a large eight-pointed star. The Star cards in these early decks differ significantly from the Star card in the standard Marseille deck, but we can find a possible precursor for the Marseille Star pattern in the Cary deck, an uncut sheet of unnumbered and untitled printed cards dating from the early 16th century.

We can see then that the iconography of the Star has taken many forms over the years. If we take this observation as a starting point, we can begin to look for Star cards to which Varo’s might bear a resemblance. And I find that intentionally or not, Varo’s design of a large star surmounting a standing figure corresponds in its general shape to the designs on the Star cards from two of the earliest Italian decks.

These two cards come from the Visconti-Sforza deck, probably painted by the Bembo workshop in the mid-15th century for the Duke of Milan, and from the uncut sheet of block-printed cards in the Budapest Museum of Fine Arts, which probably originated in Venice or Ferrara also in the 15th century. The Budapest Star portrays a standing nude male figure reaching up with his left hand to a large eight-pointed star just above him; he holds the bottom ray of the star in his hand. In contrast to Varo’s star this star is separate from the figure, but the general composition of a standing figure surmounted by a large star is the same, or similar enough, and it’s notable in this regard that the star is in contact with the figure’s head. The figure on the Star from the Visconti-Sforza deck is closer to Varo’s figure than the figure on the Budapest card. The Visconti-Sforza Star depicts a woman wearing a blue dress with a red drape, standing on a grassy ground. Like the figure on the Budapest Star, she reaches up with her hand to hold an eight-pointed star, this one delicately painted in gold. The star is less prominent relative to the figure than is the star on the Budapest card, but the drapery and grassy setting do bear a similarity to Varo’s card.

To be sure, the differences between Varo’s card and these early Star cards, including the Budapest and Visconti-Sforza cards, are significant. The open robe and coiled line on Varo’s card has no equivalent in any other Star cards, nor do the snake heads the figure holds, and it would be hard to make the case that they somehow represent stylized water jugs. That Varo’s star features five rays rather than six or eight also makes it unique among the patterns found on these historical decks, although this would seem to be a minor point. The discrepancy in the number of rays may not be of any significance for the Star’s symbolism, and thus would count as only an accidental feature. Varo’s choice of a pentagram with which to portray the star may simply reflect a borrowing from a commonly understood convention for portraying a star. On the other hand, it may reflect Varo’s deliberate allusion to an occult symbol. And I don’t quite know what to make of the coils inside the figure’s open robe (or hollow abdomen) culminating in the two snake heads. Do they represent its stylized viscera? An allusion to the Hermetic caduceus? I just don’t know.

In any event, if Tarot Card is meant to represent the Star it does so in an unconventional manner. By contrast, consider Varo’s friend Leonora Carrington’s own painting of the Star, which was created around the same time as Varo’s. Carrington’s Star hews closely to the Marseille pattern, but shows the kneeling woman facing right instead of left – an orientation that, interestingly, follows the orientation of the woman on the Cary sheet card rather than the more familiar orientation of the woman on the Marseille card. Like the Marseille, Star, Carrington’s Star shows eight stars overhead but they, like Varo’s, are five-pointed.

Although I believe Tarot Card does suggest the Star, its identity may finally have to remain a mystery. Given its unique and unorthodox iconography, it’s uncertain which card it’s meant to represent, or even whether it’s meant to represent an existing card at all. Varo may have wanted to invent a trump card completely of her own design, with her own vocabulary of symbols unconstrained by the symbolism of existing decks. It’s even possible that she just wanted to create something generically suggestive of a tarot card without claiming it as any specific trump card. As in one of Plato’s aporetic dialogues in which the interlocutors are unable to come up with a satisfactory definition of a concept, we may simply have to leave the identity of Tarot Card undecided.

Postscript:

My interpretation of Tarot Card as the Star rests largely on the compelling visual evidence of the pentagram that provides the focal point of the painting, and on some similarities I see between Varo’s card and Star cards from early tarot decks. But there is another, extra-iconographical reason I find this reading attractive, and that is the Star’s place in the Surrealist canon. One of the major works of later Surrealism is André Breton’s Arcane 17, a meditation on love, destruction, and renewal written in 1944 on Quebec’s Gaspé Peninsula, when Breton was in self-imposed exile in America during the Second World War. The work’s title is a reference to the Star card as occultists know it, as the seventeenth element within the Major Arcana – their name for the tarot deck’s trump suit. If for many of the original, 15th century users of the deck the card alluded to the Star of Bethlehem, for Breton it was a multifaceted symbol of hope, illumination, and regeneration which provides one of the book’s organizing images. It was “the Dog Star or Sirius, and it’s Lucifer Light Bearer and it is, in its glory surpassing all others, the Morning Star” (Breton, p. 68). Breton equates it as well with the “Angel of Liberty” (Breton, p. 95).

More provocative is the case of the Jeu de Marseille, the deck of 52 cards designed by Breton, his then-wife Jacqueline Lamba, and several other Surrealists as they waited in the unoccupied city of Marseilles for passage out of France following the German invasion of 1940. Varo too had come to Marseilles in an attempt to leave Europe for North America and was there at the same time as the Surrealist refugees. Although she didn’t live in the same villa as Breton and some of the other Surrealists she participated in the group’s social life, which included games such as exquisite corpse (Kaplan, p. 75). And Jeu de Marseille. What’s intriguing about the Jeu de Marseille deck relative to Varo’s Tarot Card is that it replaced the standard French suits of clubs, spades, diamonds, and hearts with the suits of Knowledge, Dream, Revolution, and Love, each with its own expressly design symbol. The symbol for the Dream suit was a star — “l’etoile de rêve,” or “the star of dream.” Its court cards comprised Freud as the Mage (the anti-royalist Surrealists’ replacement for the King); Alice of Alice in Wonderland as the Siren, replacing the standard deck’s Queen; and Lautréamont, author of Maldorer, as the Genius, in place of the Jack or Knave. The suit of the star was the suit of the imagination and the unconscious, and thus of freedom – prefiguring Breton’s casting the tarot’s Star as the symbol of the Angel of Liberty a few years later. Did Varo know of this deck, perhaps playing the game during her stay in Marseilles, and could the memory of it have played a role, consciously or not, in the design of her own tarot card? I don’t know. But the former seems likely, and the latter doesn’t seem impossible.

In the end, I don’t know if either of these Surrealist landmarks contributed to the creation of Tarot Card. But if together they don’t form a unison, they certainly do harmonize.

References:

Tere Arcq, Laura Balikci, Caitlin Haskell, and Alivé Piliado, “Witchy Worlds: Summoning Remedios Varo on All Hallows Eve,” Art Institute of Chicago Inside the Exhibition, 31 Oct 2023, accessed at www.artic.edu/articles/1094/witchy-worlds-summoning-remedios-varo-on-all-hallows-eve.

André Breton, Arcanum 17, tr. Zack Rogow (Los Angeles: Sun & Moon Press, 1999).

Ronald Decker and Michael Dummett, A History of the Occult Tarot 1870-1970 (London: Duckworth, 2002).

Janet A. Kaplan, Remedios Varo: Unexpected Journeys (New York: Abbeville Press, 2000).

Robert O’Neill, “The Iconology of the Star Cards,” accessed at www.tarot.com/tarot/robert-oneill/star-cards.

Claire Voon, “Revisiting the Lost Tarot Deck of Surrealist Leonora Carrington,” Art & Object 2 August 2023, accessed at www.artandobject.com/news/revisiting-lost-tarot-deck-surrealist-leonora-carrington.

For an analysis of Varo’s painting The Juggler (The Magician) see my earlier piece here.→

Daniel Barbiero is a double bassist, composer and writer in the Washington DC area. He writes on the art, music and literature of the classic avant-gardes of the 20th century and on contemporary work, and is the author of the essay collection As Within, So Without (Arteidolia Press, 2021).