Pediments: Ridgewood

Randee Silv

February 2014

“Start-up galleries are opening; middle-tier galleries are holding their own, or doing better than that. Artist-intensive neighborhoods like Bushwick and Ridgewood are still affordable, companionable and fun,” New York Times art critic Holland Cotter recently wrote. I had to laugh.

The Clintons spotted at Roberta’s. Bushwick featured in HBO’s Girls. Gallerists want to be in the “in.” Non-stop waves of speculators. Artists lose studios. Shopping malls? Doormen? Another write up. Real estate on the “upswing” heading towards Ridgewood? I’ve been watching as blocks keep changing personalities farther out on the “L” train beyond saturated Williamsburg. Some faster than others. Morgan stop went first. Then Jefferson. DeKalb. Myrtle-Wyckoff is quickly following.

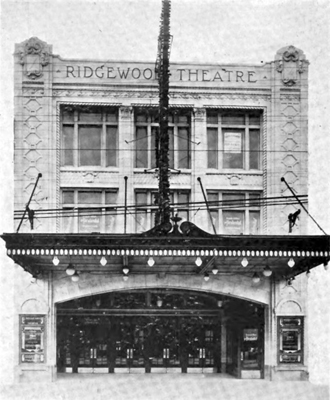

SAVE THE RIDGEWOOD THEATER posters are no longer taped on the vacant ticket booth window on Myrtle Avenue. Designed by acclaimed architect Thomas Lamb, his 1916 exterior façade was landmarked, but the community rallying to protect the original interior decor was unsuccessful. The expansion to five screens in 1980 had already left it vulnerable to damage.

Residents fought for cultural options. They talked about the emerging local “art scene,” property values on the rise, restoration grants and tax credits obtainable, but its recent 7 million dollar sale will turn the theater into 40 condo units above with retail space below.

I knew it would not be easy to find a place in 1999 after I had given up my apartment before moving to Europe. An East Village neighbor forced to relocate, heard about cheap rent stabilized apartments somewhere out in Queens. Credit checks were not required. Rows of six family houses, all looking the same, lined the neighborhood. We found a $600 railroad on a street that didn’t overlook the “M.”

The block I live on was recently designated a historical district. It had been built on the Meyerrose Farm property bought in 1911 by developer Gustave Mathews for the next expansion of his business.

Mathew’s family had emigrated from Germany like many before them and found a thriving community with established breweries, knitting mills, sewing factories and banks, where indigenous peoples such as the Maspeth and Matinecock had once fished, farmed and hunted before Dutch settlers started growing lettuce, corn and potatoes.

Mathews & Sons Realty and Construction Company found the perfect niche for needed housing. The construction of cold water flats with windows in every room, shared light shafts, private bath and full kitchens were advertised as the answer to the overcrowded “slum” conditions of Williamsburg and the LES. Rent was $18-20 a month or a building could be bought for $6,500. They were marketed as a solid investment if the owner lived in one apartment and rented out the others. Selected by the New York City’s Tenement House Department as the “most up-to-date method of housing for the masses at minimal cost,” Ridgewood was put on “the map.”

Architect Louis Berger had apprenticed with the prestigious New York Beaux-Arts firm, Cárrere and Hastings, which won the 1897 competition for the New York Public Library. He had specifically worked into Mathews’ budget similar neoclassical architecture, modern and in vogue.

Berger’s polychrome symmetrical designs were constructed with local pale yellow and amber Kreischer bricks from Staten Island that met the new fire codes. Patterned arched frames accented windows. Renaissance-Revival style galvanized iron cornices on roof ledges diverted rainwater from walls. Bands of garland motifs continued from each building to the next. 5,000 buildings in Ridgewood and Bushwick were designed by Berger between 1895 and 1930.

For the 1893 Chicago World’s Columbian Exposition, architects had been hired to design a Beaux-Arts monumental model city with a transport system and “invisible” poverty to show the public that beautification of cities could create social order. Inspired, the City Beautiful Movement expanded throughout the United States.

“Architectural Design Cult.” Writer and grassroots organizer, Jane Jacobs strongly believed that city designs couldn’t solely depend on the aesthetics of architecture alone. Cities were ecosystems. Her keen observations filled articles in Architectural Forum, and her 1961 book, The Death and Life of Great American Cities, influenced future thinking about urban planning. Her opposition helped stop plans to overhaul her neighborhood, Greenwich Village, with upscale high rises and Robert Moses’ Lower Manhattan expressway that would’ve run right through Washington Square Park.

I’ve always resisted living in a neighborhood of uniform, mass produced buildings. It took me a while to make sure I was putting my keys in the door of the right one. But, what has always caught my eye’s attention are the ornamental relief sculptures above the entrances. These hand carved pediments mark the crowning feature that reflects each building’s individual identity.

When we heard that Ridgewood had a gallery in a Mathews Flats basement on Gates Avenue, we figured it had to be a rumor. Only open on weekends. We walked over for a Sunday salon. Famous Accountants had an irresistible buzz. They closed a year later. A neighborhood with limited commercial space, a few converted buildings on the far Ridgewood/Bushwick border over on Troutman house a chunk of galleries and studios. The DYI music and art space Silent Barn had its start in Ridgewood before zoning laws shut them down. Trans-Pecos is there now. There’s a gallery on Seneca, Palmetto and Norman and an Artisan Market in Gottscheer Hall. Art crawls have followed.

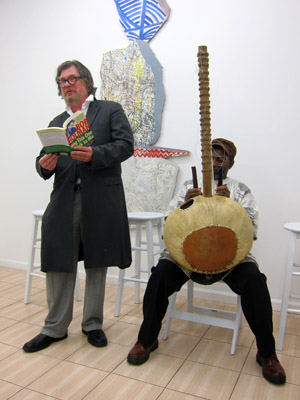

I went to a poetry reading at a gallery close by. Finally, a short walk to something besides the post office, library or subway station.

Ridgewood Theater, 1918, photo: American Guild of Organists

Mathews Flats Block, Ridgewood, 1914, photo: Brooklyn Eagle

Ridgewood Pediments, photos: Randee Silv

Bob Holman & Salieu Suso, Outlet Gallery, Bushwick, photo: Randee Silv