A Personal 360º

patrick brennan

December 2018

Mike Faloon’s The Other Night at Quinn’s

Think global. Act local.

Mike Faloon crazy quilts a network of welcome improbables in The Other Night at Quinn’s: New Adventures in the Sonic Underground, a book ostensibly about that globally influential cross-cultural African-American music (that’s become, for the most part, homelessed in its own country of origin) identified by many people as jazz. However, Faloon leapfrogs in and out of his ear&eyewitness contact with performances in a specific location (Quinn’s in Beacon, NY) to a wide spectrum of associated musings and observations that meanders a reader through a very different tapestry than flat-out critical journalism would deliver.

Criticism of any art, whether visual, performance, cinematic or sonic, navigates a delicate sierra edge. Writers who mediate between artists and audiences are usually not practitioners, a distinction that renders them valuable for the diversity of perspective they add and equally suspect for the amplified influence of their often second hand understandings. They may function as decoders, translators and proponents, or as public relations hacks, or as gatekeepers. Press (essentially hyperdistributed hearsay) can make or break how far an artist’s public activity reaches. An almost entirely Euro-American combine of publishers and writers, for all practical purposes, policed African-American artists via their domination of press outlets and distribution well past the influential emergence of Amiri Baraka/LeRoi Jones in the 1960s.

Jazz criticism has, more often than not, issued pronouncements through a persona of panopticon authority (a mask adopted during much critical writing on the arts), enforcing a historical canon of who’s who and measuring newcomers by that — this, right alongside hottest new thing tropes and who’s the moldy fig of the moment or otherwise unworthy of note … or worth being ignored entirely).

Irony especially comes to the fore as one gets to know the people behind the words. Many writers are passionate and informed listeners, often as underpaid, frustrated and neglected as the musicians they cover and frequently having to contend with editors most committed to giving coverage to musicians who record on labels that advertise significantly on their pages.

(Free speech is just wonderful, especially when you can foot the bill. In fact, U.S. legal precedent has decreed that finance is a form of speech of equal or greater value than words — let’s not even start up about ideas, imagination, questions or actual people. Often the power is less in the insight of the writer than in the amplitude of the platform. Think about how the U.S. mainstream media could so breathlessly promote deadly wars against people in Iraq or of all the free advertising donated in 2016 to one particularly toxic real estate shark.)

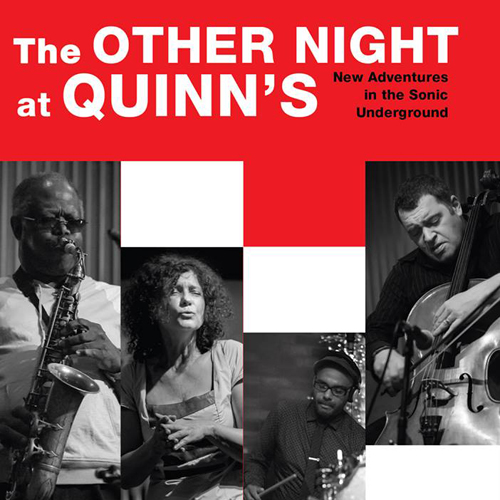

The Other Night at Quinn’s came into existence well outside of that labyrinthine echo chamber and refreshingly outside of its predominating narratives, which makes it worth reading and talking about. It’s been handsomely printed by L.A.’s Razorcake/Gorky Press, a non-profit that has already published twenty-two books of all sorts, from comics to novels to poetry, as well as Razorcake, a bi-monthly zine covering DIY Punk culture. The book is beautifully proportioned to the hand with a front cover that collages photos of four of those who have performed at Quinn’s.

One partisan reader I’ve conversed with was dissatisfied with the disparity between cover and contents, as the cover invites an anticipation of some in depth discussion of the music itself, which is still all too rare. On opening the book, the first page greeting the reader reads “Praise for Mike Faloon,” where Kevin Dunn of Global Punk writes in his blurb that he’d “rather read about Faloon’s musings on baseball or jazz than listen to or watch either.” Cover designer Todd Taylor is quoted later referring to “a jazz book that’s not really about jazz.” I disagree in some way with all of these completely valid interpretive perspectives.

Like the latter two commentators, Faloon’s listening experience, previous to encountering Quinn’s, had been much more of punk rock than of anything resembling what’s often called jazz, especially what’s called its “avant garde” (although this broadbrushes a somewhat rank oversimplification of the actual range of his listening experience). He’s also worked significantly as a drummer in that community (punk) and feels an equal passion for baseball on par with the Black Mountain rooted New York City writer Fielding Dawson. One of his earlier books, Fan Interference, identifies itself as “a collection of baseball rants and reflections.”

That his discovery of a Monday night series of what’s often clumsily tagged as “out” jazz at a more than half century old diner in a once backwater Hudson Valley town resuscitated by the petroleum funded Dia Foundation’s parking of much of its aesthetic bitcoin in a museum across the river from a Detroit styled Newburgh would engage him deeply enough to develop an entire book around it is testimony not only to Faloon’s openness, curiosity and sensitivity, but to the power and resilience of the music that drew him in. How can it not be about that music? Faloon’s initial starting distance from his subject magnetizes his prose and enables him to convey the revelatory sensations of witnessing a music for the first time in a way that no already practiced aficionado could.

Punk rock as an navigational north star orients a vantage opportunity regarding the goings on at Quinn’s. One might habitually expect the dismissals that preferring musings over the music, or a book about the music that’s not really about the music, would imply. Conversely, a random first listen to some punk rock might, to a more jazz seasoned ear, impress as some powerfully amplified, de-bluesified nursery rhyme melody boxed into some uniform rectangular beats. Mass and drive, absolutely, but, so it seems, punk doesn’t really have the funk, does it? (of course, nothing’s ever really that simple) Listening to trumpeter Jaime Branch one night at Quinn’s, Faloon writes:

… There’s a density that I’ve not experienced before, something redemptive, reassuring, bigger than me. It’s like the first time I heard the Minutemen. A friend asked me to make a copy of his 3-Way Tie for Last cassette. I didn’t know anything about the band or underground punk. I thought that I would set the tape-to-tape deck in motion, confirm my negative assumptions about punk rock, and leave the room. Instead I stayed slack jawed, glued to the band’s live wire crackle and squawk, my eyes opened to colors I’d never before seen.

But, as one segues from sound to disposition, additional pathways emerge. Punk’s full throttle commitment and energy, its uncompromising rejection of the lie-pablum that justifies mainstream “consensus,” the solidarity of its Do-It-Yourself ethic are not so distant from the motivations, attitudes and strategies of, at minimum, the least risk averse of jazz practitioners.

And, beyond the more commonplace perception of punk as rooted primarily in British working class dissent (Bad Brains aside), some now point to a precursor in the early 70s Afro-Detroit rock trio, Death, who themselves saw what they were doing as extending the take-no-prisoners Detroit attitude most exemplified by the MC5. The MC5 were able to scare even Jimi Hendrix, and although without the skills to go where SunRa could, they nevertheless consciously emulated Ra with Starship / Starship take me / Take me where I want to go….

For the generations of African Americans who’ve had to organize their own mutual aid societies within the terrorist enforced isolations of U.S. apartheid, DIY has been no option, but frequently the only solution available. In the 1950s, Charles Mingus and Max Roach formed Debut Records as an artist owned alternative to the nickel & diming treatment routinely disposed by the record industry. The Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians in Chicago, Strata and the Detroit Artists Workshop, the Underground Musicians Association in L.A., Black Artists Group in St. Louis, and, in New York City, the Jazz Composers Guild, Jazz Composers Orchestra Association, Studio Rivbea, The Ladies’ Fort and Ali’s Alley were among some of the 1960s and 70s initiatives by artists to take control of the presentation of their work. The Stone, Arts for Art, Stephen Gauci’s Bushwick Improvised Music Series, Andrew Drury’s Soup & Sound and a whole flush of other house concerts present just a few current instances of the same aspiration in action (and, for a good number of years before closing for renovations, the squat ABC NoRio, an indisputable hub for Punk aesthetics, hosted a Blaise Siwula’s C.O.M.A. Sunday evening improvised music series). And then, one also has to note the decades upon decades of writer initiated, small presses. Punk may often have been celebrated as practically an originator of DIY, but it’s clearly been participating in what’s a much, much longer tradition.

It’s hard to imagine an actual scenario where jazz practitioners would actively bar audiences from listening to their music, yet an image persists of a recondite jazz world unintelligible to outsiders as if it were some sort of closed, secret society. Now, it is true that the music’s accumulated internal resources are more than able and willing to go sophisticated and deep. It’s also true that it can’t really be heard if framed strictly as “entertainment” (although Louis Armstrong, for example, managed to finesse that role almost seamlessly, many boppers took exception to it for some very sound reasons) and this seems to be the rub that some potential listeners might tend to chafe at.

The musicians themselves are risking a special faith in listeners. In refusing to play down to audiences (to apologize, or dumb down, to distract from, or try to make more fluffy and comfortable), they demonstrate a confidence that listeners have, or can discover, the capacity to themselves compose along with the music as it happens, that they are meaningful participants rather than incidental consumers.

Sometimes, there’s a misapprehension that a listener must be versed in music theory, history and jargon to catch what’s happening. And, while musicians may make much practical use of such tools, the music communicates primarily as theater, as the interpersonal drama that it actually is. This is where Faloon is especially awake. He knows how to wait, to listen and to watch; and the wondrous parallel with this is his skill in transmitting what he encounters into words.

What most gives Faloon’s writing here such authority is his commitment to the local, to the limits of his own body and experience. He doesn’t bluff knowing more than he knows. He trusts his own senses and imagination. He trusts what’s in front of him. He trusts what happens to him as he engages a performance. There are the sounds and the musicians, but there’s also what he associates with, both in his imagination and in his environment. He notices the band. He looks around and catches the ambience of the room. He notices how people are behaving. There’s the weather, and there are the Mets, what he did while teaching that day, the automobile discovered buried whole in his own back yard, a scene from a film or a section of a book, what his kids have been up to. Everything connects to everything else.

His looping, interior voice invokes intoxication. A reader can get all wrapped up in his turns of mind, unable to put the book down as if instead reading a sort of suspense narrative. But, it’s not really about suspense; one begins to care in a very personal way, to participate in his thinking, to begin imagining conversations with the writer, to wonder along with him. Although the book’s continuity is not in the least novelistic, the effect of getting inside the mind of someone other than oneself can nevertheless saturate a reader in a way that novels so often aspire to.

These Adventures in the Sonic Underground wander, and deliberately so, like mycellium. Faloon recognizes performance as a focal node in an expanded social ecology, and his attention follows the offshoots, backflows and feeder streams of that more evident current. Most chapters read as they were initially cast: ruminative individual articles, each about a particular performance on a particular night, all sequenced chronologically in a way that allows one to traverse Faloon’s own evolution with the music over this more or less 2 years of listening.

From the very start, his perceptions are never naïve, but always perceptive and astute. The later installments, however, elaborate more in depth, often supplementing his accounts with conversations with the musicians about their music, as he accomplished superbly in his chapter All Going out Together about Jason Kao Hwang’s Sing House.

In-between chapters trace the environment that’s spawned the Monday night series (as well as an experimental music series titled Extreme Thursdays). He researches the history of Beacon and of Quinn’s’ previous owners going back into the 50s with lifelong denizens Bev & Joe Turey and Betsy Ann Coughlin. He interviews co-owner Steve Ventura, whose ardent enthusiasm for music motivates programming that often defies the profitable. Musician, instigator and frequent curator James Keepnews speaks during a parallel interlude. Faloon devotes a chapter each to Quinn’s patron and listener Eric Porter as well as musician bartender Mark Pisanelli along with individual musician profiles of Joe McPhee, Mary Halvorson and Andrew Drury. The book is additionally enhanced throughout with Michael Bogdanffy-Kriegh’s photographs of Quinn’s performers.

Sidestepping the embarrassingly blunt crudities of southern “hospitality,” the Jim Crow of the urban north has been engineered with the smoothly polished, plausible deniabilities of the professional class. New Deal inspired housing and homeowner initiatives often systematically excluded a significant sector of the U.S. population, and, with the collaboration of bankers who redlined prodigiously in order to segregate neighborhoods, managed to incentivize color coded zones of urban decay, areas so starved of resources that many white identified Americans could be persuaded that all this was exclusively the fault of the people residing there. CO2 driven, “Morning in America” suburbanization only further exacerbated that misappropriation while intensifying a general contempt for cities and urban life.

By 1975, an insolvent New York City had become as hostage to financiers as any “third world” country had to structural “adjustment.” Nobody “wanted” to live there (and some just couldn’t afford to leave), except, for example, artists, actors, musicians, dancers and other sorts who tend not to flourish without a convivial, cross-cultural public world. The city’s bankruptcy-ignited fire-sale opportunities soon excited real estate predators into jump-starting what over decades has crystallized as that incrementally ever more ruthless social engineering known as gentrification. The first to be dispossessed, no longer able to find a room, even for a night, soon populated the emerging new boom in homelessness to make room for much more remunerative young urban professionals and their more suburbanized mentalities and expectations.

This social pressure, the application of ever higher costs of living to eliminate, among other things, such marginal, so-called economically “unproductive” activities as open time to think and imagine, apparently gratuitous, random social gathering, experimentation, reading, making friends, curiosity, music, mistakes, conversation, art and so forth has been cumulatively retuning the tenor of the Hudson valley as more people jump (or avoid altogether) the ever so upgraded NYC luxury cruiser for a little more spacetime to breathe.

Quinn’s still looks like a vintage mid-20th century diner with just a little extra makeup added here and there. It serves excellent, very reasonably priced ramencentric dishes. No cover charge is asked of patrons, but eloquent speeches, often by James Keepnews, urge those present to donate via a contribution box. Being so small an operation, Quinn’s can only afford a small proportion of what working musicians merit, but even under these tundra fragile conditions, and without inputs such as the random foot traffic of a Manhattan location, the restaurant and the various music series on various nights have managed to stay afloat, if not thrive.

Although positioned a good distance from metropolitan population densities, Quinn’s nevertheless fosters conditions kin with what David Byrne ably describes in an otherwise more facile than not book entitled How Music Works, a scene. Based on his experience of how CBGBs spawned its now “legendary” scene (one should remember that, just up the block during in the late 70s, the far less fame endowed (and less “white”) Tin Palace hosted many early NYC performances by David Murray, Air, Black Arthur Blythe, Olu Dara, Julius Hemphill, Butch Morris and Oliver Lake), he advises that venues should not charge musicians to hear each other and there should be no backstage for performers to disappear to. Quinn’s delivers those parameters in a way now almost impossible to sustain in the rent-death, pay-to-play squeezathon of the big city downstream.

None of this would necessarily predict the existence of Quinn’s. The diversity of its patronage, including those convinced in 2016 of the most fanciful of HRC conspiracy theories (as reported in the book’s epilogue), reconfirms that this bar-restaurant rests in no bohemian enclave. Quinn’s happens because of the very personal motivations of its owners and committed proponents, arguably, in that regard, therefore, a social miracle of sorts, and one well suited to the equally personal probings of a Mike Faloon. Regulars, almost immediately, warmly greeted the new guy sitting at the counter with the open notebook, friendships developed, after-gig hangs peppered evenings with conversation, and a series of articles evolved finally into a remarkable book about situations usually only dimly remembered by those who just happened to have been there.

Faloon’s prose is economical, elegant and fluidly readable. Many of his chapters almost cinematically crosscut seemingly unrelated narratives that nevertheless evocatively call to each other across their differences to cohere in a way more rotating panavision than collage. There’s a loose limbed quality to all these components; the gaps among them feel like a wind that a reader might travel on, and in that less determinate ambience, actually absorb the lateral depth and blendings that situate these musical events at Quinn’s without one actually having been there. He achieves a multi-nuanced presence through deflection and indirectness, the way a sly curve ball might snag some periphery.

Yet, each specific moment is rendered with Hasselblad precision and attention to significant detail. Analogies with baseball discourse actually turn out to be pretty apropos. He’ll describe a musical episode like an old school radio announcer running down an intricate double play or a base stolen after the left fielder unexpectedly stumbles. The Other Night at Quinn’s really is about the music, even though it may travel hither and yon along the way, because the music’s about more than the sound, but also about its interaction within a total environment.

Bassist Ken Filiano has mentioned that the writing reminds him of the Beats, and its footloose breadth does favorably remind me a bit of LeRoi Jones’ notes to Trane’s Live at Birdland, that’s true. The textural intercutting strategy also recalls the painter-poet Basil King, and there are likely a good number of writers adopting this tack in various ways to good effect.

But, Faloon’s not emulating any derivative, well stylized rehashes. He’s got his own well grounded, well earned personal voice. And, rather than positioning that voice outside these events, he narrates as from the center of everything that’s going on around him, and, concurrently, we can listen along with him, from within that hurricane’s eye that can hear the music so up close.

Link to Mike Faloon’s The Other Night at Quinn’s on Razorcake

◊

patrick brennan coordinates ensembles, composes & plays the alto saxophone, pursuing a contrarian and independent musical path toward evolving a distinct musical language that explores multidirectional thinking, organization, time, sound, line & rhythm. Recordings include terraphonia (Creative Sources), muhheankuntuk (Clean Feed), .which way what, and Sudani (deep dish).