Migration of the Dot: Red

Randee Silv

February 2014

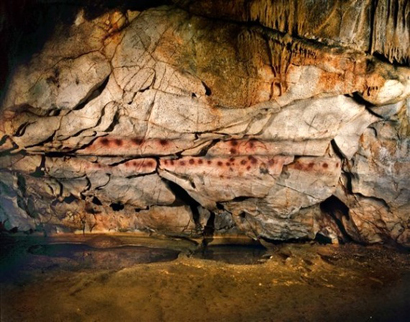

Round. Red. 40,800 years old. Fifty samples tested from eleven caves in Spain. One in the Panel of Hands in Cueva de El Castillo is now considered Europe’s oldest dated art, 4000 years before the black charcoal rhinoceros drawings in Chauvet, France. Dr. Alistair Pike from the University of Bristol used uranium-thorium dating in 2012 to analyze the calcite deposits that had accumulated from water seeping over the pigments on rock surfaces. Only tiny scrapings from top layers were needed. A sample beneath could date back even farther.

“Simply by comparing the dates of the earliest modern human remains currently known in Europe with the minimum age of El Castillo art, we can already say that the cave art predates modern humans to the extent of the currently available evidence.” Pike is testing other hand stencils, red symbols and disks. “You clearly see distinct styles arriving and leaving at different periods. I don’t think one can say these are multicoloured and these are monochrome to make judgements about the art or even the cognitive abilities of Neanderthals or humans.”

João Zilhão from the University of Barcelona, co-author of the research study, concluded that “It suggests that a lengthy period of geometric or abstract art … in both Africa and Europe, preceded the emergence of figurative representations. If anything, it argues for a middle Paleolithic revolution, not an upper Paleolithic revolution.”

The air slightly cool. Footsteps echoed. We walked in almost complete blackness. I was tempted to stray off the marked trail. I got as close as I could to absorb the red circular shapes in the Panel of Hands. You had to be fast visually as his flashlight quickly gave focus. He rushed us past the Corridor of Disks. I wasn’t able to convince him to stop long enough for me to count them. I lagged behind. He insisted that I hurry along. Time had to be restricted to limit the amount of body heat and moisture from our breath. Our group exited through the expanded entrance constructed for archeological excavations of what remained from human occupation 150,000 years back.

French specialists rejected Marcelino Sanz de Sautuola’s claim that he had found Ice Age paintings at Altamira in 1879. He was accused of forgery and suspected of having hired artists to do the work. Twenty three years later, his discovery was accepted.

Green mold found on the paintings in the main chamber forced Altamira to close in 1977; and with conservation efforts, limited access was permitted until 2002. Protected as a World Heritage Site, visitors could only view the polychrome mural in a newly built replica of the Great Hall. UNESCO has just announced plans for an experimental reopening. Five random visitors a week wearing “disposable overalls, caps, gloves, masks and special footwear” will now be allowed.

A holographic cave family sitting around a fire greeted us. The guide proudly repeated “After Altamira, all is decadence.” If I’d told her that Picasso had never said that nor been there, I don’t think she would’ve believed me. According to Paul Bahn, a leading archeologist on cave art, it was just an overused promotional line. Maybe they were confusing it with Joan Miró’s comment that, since cave dwellers, “Art has done nothing but degenerate.” I was disappointed that the meandering macaronis traced in clay were nowhere to be seen.

“Urged on by my eagerness to see the many varied and strange forms shaped by artful nature, I wandered for some time among the shady rocks and finally came to the entrance of a great cavern. At first I stood before it dumbfounded, knowing nothing of such a thing; then I bent over with my left hand braced against my knee and my thigh shading my squinting, deep-searching eyes; again and again I bent over, peering here and there to discern something inside; but the all-embracing darkness revealed nothing. Standing there, I was suddenly struck by two things, fear and longing: fear of the dark, ominous cavern; longing to see if inside there was something wonderful.”

This personal anecdote, found among Leonardo da Vinci’s papers, affected the Chilean painter Roberto Matta, who pointed out that da Vinci had also said “that it was very boring to start with a white piece of paper and put a line on it, because all you are doing is putting what you know in the paper. He said you should start from a spot on the wall, humidity. If you look at a spot for awhile, he said, something will start appearing by a funny process called hallucination. He would see whatever came in the hallucination. He said to follow that image. …If I see in the spot on the wall something I know, I erase it and wait until something else comes along. And then I see something which to me is fascinating because I don’t know what it is. …That’s what I told the School of New York…”

The guide opened the locked gate. He talked about findings from the settlement at the mouth of the cave. You could feel a sense of presence. He only turned on the dimmed lights when necessary. We continued down a long winding path towards the main frieze below. You could clearly see the outlines of hinds, of a goat and a horse that had been painted using tiny red dots, some still clear, some worn. He handed me a gift of a small engraving burin that he had picked up. This one would go unnoticed by the researchers who cataloged every object unearthed.

Groupings of dots might have signaled “acoustical zones,” according to ethnomusicologist Iégor Reznikoff, who studied the resonant quality of sound, its intensity and duration, in relationship to the placement of images. Natural echoes acted like landmarks or gave directions into miles of cave passages. “Resonance is the only way to know how long or deep the space ahead is.”

We arrived early morning to Pech Merle only to find that the first tour was already full. They crowded us in and all you could hear was chatter. I was hoping that maybe clusters of dots would guide us instead of his laser pointer. I knew he’d been told to complete the outlines of every leg, neck, back, tail, horn and mouth of each animal painted on the protruding rocks. I preferred focusing on their unrecognizable strokes. He suggested that we stare at them and imagine a shimmering yellow-orange glow from torchlight. I did squint my eyes to watch how they flickered and moved. I asked about the abstract marks, there were so many; but I seemed to be the only one interested. I peered into the alcove that he said had probably been a gathering space for women. He mentioned that a high percentage of stenciled hand prints were female and that DNA evidence had confirmed that the spotted horses depicted in one panel actually did exist 50,000 years ago.

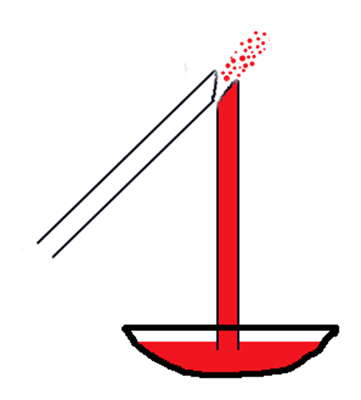

Iron oxide deposits were plentiful, ground into powder, then mixed with binders of animal fat, blood, vegetable juice, and urine to help it adhere. Women and men painted by lamps made from moss burned with a lump of animal fat. Researcher Don Hitchcock describes a possible airbrushing technique: “Two hollow bones are used, one set perpendicularly in a container of water and ochre, the other is held in the mouth. When the artist blows across the open hollow bone, the reduction in air pressure forces the ochre up the vertical hollow bone, at which point it is blown onto the rock surface by the jet of air from the bone held in the mouth of the artist.”

We rode through Grotte de Rouffignac on an electric train, making stops to look up at embedded finger flutings. Some of these undulating marks left on the walls could be confused with those from bear claws. Researchers had recorded the widths of these single, double, triple swirling lines and concluded that many of them had been made by children between two and seven years old. Archeologist Jessica Cooney noted that “Many theories about cave art point to shamanism or ritual use. While I don’t rule that out, I don’t think that that’s necessarily the case for all caves. With children involved, it could have been one of those reasons but also very likely could have been play or a time for practicing art, or simply an exploration of the landscape.” We departed through a catherdralesque space with heights we hadn’t seen elsewhere.

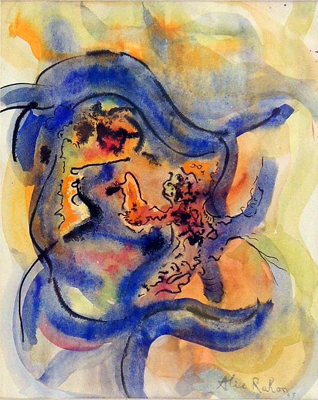

Austrian painter Wolfgang Paalen and French poet/painter Alice Rahon visited Altamira in 1933 and later settled in Mexico on the invitation of Frida Kahlo. His fumage paintings, using smoke and soot from burning candles on wet paint, were seen in a 1940 solo NYC exhibition at the Julien Levy Gallery.

Introduced to Paalen through Matta while in Mexico, Robert Motherwell received what he referred to as a “post-graduate education in surrealism, so to speak.” Motherwell’s illustrations appeared in Dyn, the international art journal edited and published by Paalen. Contributors addressed new possibilities in art & thought with writings on abstract surrealism, totemism, First Nation and pre-Columbian cultures, wave mechanics, quantum theory, all mixed in with poetry, photography and images from painters and sculptors.

Motherwell included Paalen’s book of collected essays, Form & Sense in his series, Problems of Contemporary Art. The influential ideas of Paalen, who was seen as an “intellectual secret agent,” circulated among the emerging New York School.

A 50s Ad Reinhardt cartoon on abstract art quoted from a phrase in Form and Sense: “Paintings no longer represent; it is no longer the task of art to answer naive questions. Today it has become the role of the painting to look at the spectator and ask him: what do you represent?”

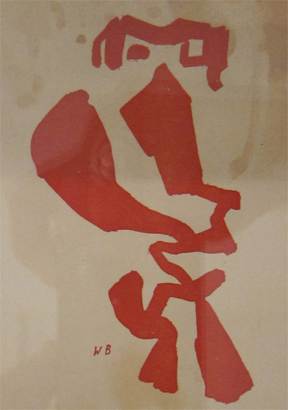

German born sculptor and architect Mathias Goeritz worked in “pure abstraction” and, along with Paalen, was part of Mexico’s Generación de la Ruptura. His manifestos addressed modern thinking while criticizing the frivolousness of the art world, advocating a return to “abstract simplicity” and “collective authorship.” He moved to Santillana del Mar in Spain and founded the School of Altamira in 1949 where he was joined by Willi Baumeister, Angel Ferrant, N.H. Stubbing, Eduardo Westerdahl, José Artigas, Eduardo Saura, Joan Miró and others. Meetings were often held in the cave.

Two conferences of the School of Altamira met in Santillana. They published a journal, Bisonte and, according to Robert Hobbs, advocated that “Cro-Magnon art of the Magdalenian period represented a touchstone for all of humankind. Convinced that art had not developed since then—it had only changed and succumbed to fashion—they wanted to return to what they believed were the very beginnings of art and humanity.” The group disbanded after rumors circulated about “communistic connections.”

“My favorite schools of painting are as far back as possible: the cave painters—the primitives. To me the Renaissance does not have the same interest.” – Joan Miró

In the Art in the Age of Altamira exhibition catalog, Jill Cook wrote that, after his cave visits, “Miró’s preference for working off the easel on larger format works painted against a wall or on the ground, as well as his use of ochre pigments and earth tones developed. ”

While living near Altamira, N.H. Stubbing came to know its “vocabulary of shapes.” His wife, Yvonne Hagen, wrote about his transition from portraiture and landscape painting to abstraction. “Transfixed by the paintings at Altamira, Stubbing asked himself what did the works on the wall mean? Were the bison paintings at the entrance of the cave — colored with blacks and ochres — executed to cast magic spells? He began to enter the world depicted around him, letting it inspire new concepts in his paintings. He was struck by the thought that the best of modern art was somehow close to early man.” Stubbing went on to paint with only his bare hands for the next twenty years “in an ultimate gesture of commitment to the first artists in the caves.”

As the elevator door opened, I immediately felt a visual trance. Circling between the recent exhibition of Indian Space Painters to my left and paintings by John Ferren, Herman Cherry and Kyle Morris to my right, I soon found myself staring into the dense darkness of Cave of Black (Black Painting #6) 1954. The adjacent information at the David Findlay Gallery read that Cherry’s visit to Lascaux “would prove a profound one on his work.”

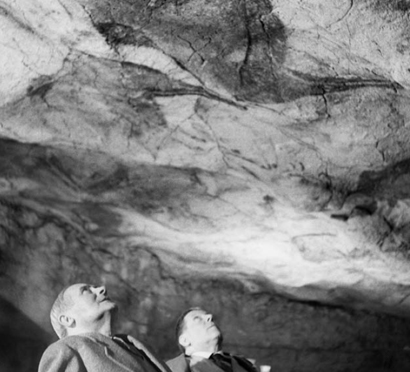

I learned afterwards that he and painter Denny Winters had traveled extensively abroad on a 1948 Guggenheim Fellowship Grant. Some American artists may have seen MoMA’s 1937 exhibition, Prehistoric Rock Pictures in Europe and Africa, or come across images in books, but few had actually ventured into the caves. Chicago’s Field Museum had organized their visit to Lascaux. There they met Abbé Breuil, a paleolithic archeologist who devoted his life to drawing detailed studies of imagery found inside almost 100 caves. Cherry had a copy of the ground breaking comprehensive survey, The Lascaux Cave Paintings, which included Fernand Windel’s photographs along with text and illustrations by Breuil. Both autographed it for him.

“It all looks like one huge painting on unsized canvas. …The rough texture of the ceiling’s surface and those beautiful earth and blood colors,” wrote Helen Frankenthaler in postcards to friends during her first visit to Altamira.

Painted from these memories, Before the Caves “exhibits the earthy colors Frankenthaler had written of in 1953 and the mix of calligraphic drawing and flat areas of pigment seen in the cave paintings. Just as the surface of the rock is integrated with the primitive artists’ material, the fibers of Frankenthaler’s canvas are one with her paint,” Susan Cross wrote.

Frankenthaler returned with Robert Motherwell in 1958 to visit Altamira and Lascaux. He spoke about his moving experience of seeing Altamira by candlelight and his “affinity with cave paintings.” Robert Hobbs points out that The Homely Protestant, “with its dark ochre color and figure defined with sgraffito markings, alludes to dimly-lit walls of caves. The diapered pattern in the background resembles ancient petroglyphs; the figure seems to be formed from undulations on a cave ‘s wall, while red skeletal parts appear to have been rubbed on with a stick. The shapes that look as if they are part of the geological conformation of the cave’s wall collaborate with drawn forms to suggest that what is presented in the painting is analogous to what one finds in the far recesses of the mind.”

“In a way cave art is closer to what’s happening today, in the immediacy of the application that, let’s say Renaissance art where you feel, ‘Well, that was then’, You don’t say, ‘That was then’ with the caves. You say, ‘That’s now.’ I felt a tremendous identification with those Paleolithic artists.”

Elaine de Kooning visited the French caves as well in 1983 and those in Spain the following year with friends, Rose Slivka, Rosalyn and Sherman Drexler.

“I found myself deep in the caves imagining that I was one of them, looking for surfaces smooth enough to paint on, noticing chunks of yellow clay on the ground that would be perfect to draw with.”

“Prehistoric art was secret—hidden away deep as though they didn’t want you to find it. The first two caves we visited—Niaux and Bedheilac—were vast cathedral spaces and we had to walk, it seemed for miles, before we arrived at the first images. …splotches of red and ochre or gleaming white calcium deposits, their rolling turbulent forms and intricate cracks and crevices. …before I saw my first actual prehistoric drawing. I was overwhelmed by its unexpected immediacy.”

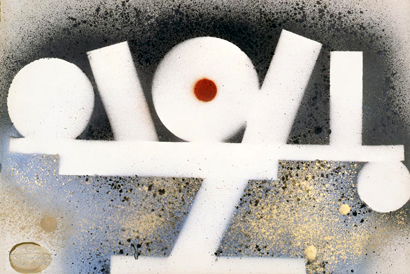

“Fifty years ago David Smith made his first spray work with the recently invented aerosol can. He was aware of the prehistoric cave paintings of Altamira. Smith and the cave artist created images by blowing or spraying paint while shielding the ground surface-rock or paper-with a hand or with a piece of metal.” Erik Saxon wrote in a review.

David Smith emphasized that cave painters “from Altamira to Rhodesia (Zimbabwe) had reproduced true reality by the eidetic image. This image even today defies word explanation as does any art.”

Lascaux was discovered after a dog chased a hare down a hole in 1940. It was closed in 1963 for restoration due to contamination from artificial lighting and 100,000 yearly visitors. Paint faded. Algae and bacteria were forming. Lascaux II opened in 1983. Surrounded by images, we lit matches to witness the shifting perspectives in the low ceilinged tunnel of the Hall of Bulls. There were plenty of rectangles, lines of dots and jagged lines to be seen, but I was disappointed that The Shaft of the Wounded Man hadn’t been re-created.

“…But these prehistoric paintings bear witness to what art was when art began. They reflect something strangely akin to our modern sensibility and, bridging the distance between then and now, leave us with the feeling that, in its ordinary sense, time does not exist.”Georges Bataille made nightly visits after the tourist crowds left.

Sculptor Bruce Beasley was invited to investigate a newly discovered cave, Chauvet, in 2000. “Preparation and smoothing of the surface prior to drawing allows for a finer and more subtle quality of line and shading than is possible on a rougher surface. This finely prepared surface also allowed the artist to scrape back and rework parts of the drawing. One can easily see where the artists used their fingers to blend and shade the charcoal…. The compositional complexity can be seen through intentionally complex overlapping and interspersing of animals, as well as groups of animals represented as receding in space…. The discovery of Chauvet has certainly dispelled any lingering idea that visual sophistication in art is progressive through time.” The cave has never been open to the public.

Miquel Barceló is part of the scientific research team for Chauvet and will oversee the reproductions of the paintings for the facsimile opening in 2014. The Spanish artist’s 26-foot tall bronze elephant standing on its nose was on view in Union Square for over a year. “I always say it’s a self portrait, because it’s like an artist in difficult times – we’re always balancing on our trunks.”

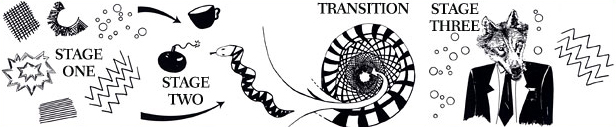

Zig-zags. Grids. Nested curves. Clouds of dots. The edges of vision. “Neurological bridge.” Neural artifacts.” The human nervous system hasn’t changed. Whether provoked through repetitive music, dancing, hallucinogenic plants, lack of food, chanting, sensory deprivation or a cave’s carbon dioxide, these visual percepts are wired into us. Oscillating. Expanding. Compressing. They mix and swirl with cultural expectations before congealing into recognizable forms. David Lewis-Williams wrote about this entoptic phenomena. Abstract marks before iconic imagery.

Interpretations. Theories. Rituals. Aura. All of this was racing through my head. We went spelunking in a local cave, Conellante. I walked through the river and crawled through the deepness of small openings. I felt my way through as my own sounds answered back. I listened to the trickling water and slight wind. We stopped in an open space at the end of the passageway. I saw her immediately nestled on the surface of the limestone wall. It was if she had been waiting there for me. I heard her thoughts. I knew she heard mine. I spoke out loud. I waited for her to fade, but she never did.

.

“Silence. I turn off the helmet lamp. A darkness. In the darkness the silence becomes encyclopedic, condensing everything that has occurred in the interval between then and now. …These rock paintings were made where they were, so that they might exist in the dark. They were for the dark. They were hidden in the dark so that what they embodied would outlast everything visible, and promise, perhaps, survival.” – John Berger

Cueva de El Castillo, Puente Viesgo, Spain Panel of Hands, photo: Pedro Saura

Cueva de El Castillo, Panel of Hands, photo: Pedro Saura

Cueva de El Castillo, Corridor of Disks, photo: Pedro Saura

Hologram, Museo Nacional de Altamira, Santillana del Mar, Spain, photo: Estudio Nómada

Inside Conellante, Matienzo, Spain, 2010, photo: Randee Silv

El Pendo, entrance, 2010, photo: Randee Silv

Pech Merle, Cabrerets, France, photo: Steve Errede, Dept. of Physics, University of Illinois

Airbrushing, photo: Don Hitchcock, Don’s Maps

Finger Flutings, Grotte de Rouffignac, France, photo: Kevin Sharpe & Leslie Van Gelder

Untitled, Alice Rahon, 1945, watercolor, 10 x 8”, photo: Creighton-Davis GallerY

L’Enclume, Wolfgang Paalen, 1952, oil & fumage, 53 x 74”, photo: Artsy.net

Message, No. 8, Mathias Goeritz, 1959, gold paint, perforated steel, pushpins on board, photo: Arevalo Gallery

Conference Poster 1950, Willi Baumeister, Centro de Arte Riena Sofia, Madrid, photo: Randee Silv

Altamira, Joan Miró, 1958, lithograph, photo: Quittenbaum Auction House, Munich

Joan Miró & Josep Llorens Artigas, Altamira, 1957, photo: Fundación Botín, Santander, Spain

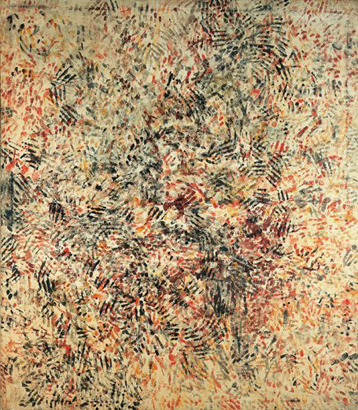

Patterns of Aranjuez, 1955, N. H. Stubbing, oil on canvas, 78 x 69″, photo: England &Co, London

Cave of Black , Herman Cherry, 1954, enamel/coffee grinds on canvas, 61 x49″, David Findlay Gallery, photo: Randee Silv

Untitled, Denny Winters, 1982, photo: Gamage Auction House, Rockland, Maine

Before the Caves, Helen Frankenthaler, 1958, oil on unprimed canvas, 102 x 104″, photo: Berkeley Art Museum

The Homely Protestant, Robert Motherwell, 1946, oil on masonite, 98 X 48″, photo: Metropolitian Museum

Cave Study (Perigord Region), Elaine de Kooning 1983, segment, photo: Artvalue.com

Lascaux Cave, France, closeup of Megalaceros section, photo: Wikimedia commons

Untitled 1963, David Smith, spray enamel on paper, 14 x 19″, photo: David Smith Estate

Chauvet Cave, Vallon-Pont-d’Arc, France, photo: Dr. Jean Clottes

Exhibition poster, Miguel Barceló, Institut Valencià d’Art Modern, 1995 photo: Michel Fillon Gallery, Paris

Stages of Trance, photo: David Lewis-Williams, Inside the Neolithic Mind

Pareidolia, Conellante Cave, 2010, Matienzo, Spain, photo: Randee Silv

Blackness, Conellante Cave, 2010, Matienzo, Spain, photo: Randee Silv

long fascinated by the origin of the red disk [dot] and include it along with the mystery in my paintings. Obviously, I am not alone under the spell.