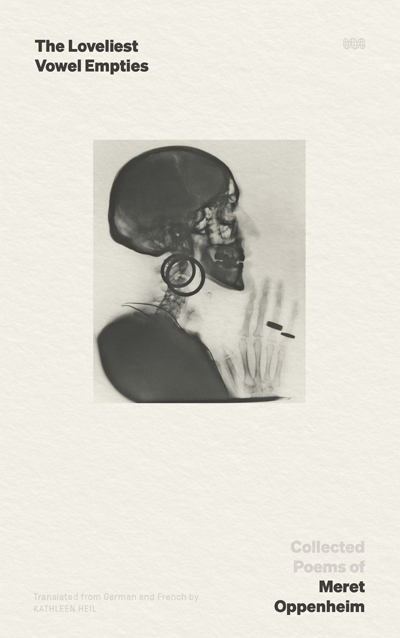

The Loveliest Vowel Empties: Collected Poems

Daniel Barbiero

March 2023

Meret Oppenheim

The Loveliest Vowel Empties: Collected Poems

tr. Kathleen Heil

World Poetry Books

At the International Surrealist Exhibition in London, held in 1936, T. S. Eliot was seen to linger over one of the more curious objects on display: a fur-covered teacup, saucer and spoon. The object, titled Objet: Le déjeuner en fourrure, was the creation of twenty-two year-old Meret Oppenheim, an artist of Swiss background then living in Paris. Although the fur-covered tea set would become of the most famous artworks not only of Surrealism, but of the twentieth century as well, Oppenheim herself would remain considerably less well-known. Now, with The Loveliest Vowel Empties, a volume collecting all of her poetry, we have access to another side of the artist behind the provocative object. It is a side that bears the marks of some of Oppenheim’s creative and other preoccupations.

Oppenheim was born in Germany in 1913 to a German-Jewish doctor father and a Swiss mother. When her father was called up into the army after war was declared in 1914, Oppenheim and her mother moved to Switzerland to live with with the mother’s parents. By the time she was in her late teens Oppenheim had gotten involved in some of Basel’s artistic circles, and decided that she wanted to be an artist. This alarmed her parents, who sent her to Jung, whom her father knew; they were reassured when the psychoanalyst told them that it would be alright. Her father suggested she go to Munich or Paris to study art; consequently, she moved to Paris in May, 1932 at age 18 with her friend Irène Zurkinden. There, she took some courses in painting at the Acadèmie de la Grande Chaumière in Montparnasse, a low-cost art school that eschewed the rigid formalism of the École des Beaux-Arts. In 1933 she met Alberto Giacometti, who visited her studio and with Hans Arp invited her to show with the Surrealists at the Salon des Surindépendants in autumn 1933. She began to associate with the Surrealists who, as she recalled it, “accepted women as artists without prejudice,” and her social group notably included not only Giacometti, Arp, and Man Ray, who photographed her, but the Surrealist or Surrealist-friendly artists Leonora Fini, Leonora Carrington, and Dora Maar. She created the famous teacup in 1936 after a playful conversation with Picasso and Maar at the Café de Flore and shortly thereafter met André Breton, who suggested the title Le déjeuner en fourrure for the piece. She stayed in Paris until 1937 when, with her father no longer in a position to support her, financial difficulty and a severe episode of depression impelled her to move back to Switzerland, where she lived until her death in 1985.

Oppenheim’s Paris years, though brief, were important to her development as an artist. It was in Paris that she began to write the poems collected in The Loveliest Vowel Empties. As she remembered it, her first poem was written while sitting in the Café du Dôme shortly after she arrived in the city. Translator Kathleen Heil notes in her introduction that most of the forty-nine poems collected here were written in 1933-1944, and with the exception of a handful of poems that originally were written in French which Oppenheim then translated into German, all were composed in German.

Given Oppenheim’s association with the Surrealists, an association that was not without ambivalence on her part and that continued intermittently after 1937, it isn’t surprising that her poems, which frequently contain startling or extravagant images, inevitably recall Surrealism. But this resemblance to Surrealism may not always be the result of direct influence for, as Heil points out, both Oppenheim’s poetry and Surrealist poetry drew from a common source in the hermetic verse of Symbolism. For instance, the brief poem “Noah’s Ark” hints at a set of private meanings attaching to its central figures of the beautiful woman in the water and the black algae that either surrounds her or attaches to her:

Fetch the beauty from the water

Dry her wet hand and

Cast the black algae

Into an iron existence

Similarly, the repetitive reference to the mother-of-pearl statue in the poem beginning “Hot hand on the cast iron fence” carries an apparently forceful significance, albeit one that’s difficult to decipher. But it appears to be allied to the kind of obsessively recurring object one might encounter in a dream.

And in fact many of Oppenheim’s poems do have an overtly dreamlike quality. The poem beginning “The forests and fields are no longer visible,” for example, originally written in French, describes a bucolic scene at sunset in increasingly hallucinatory metaphors, while the poem beginning “Where is the carriage heading?” traces a series of abrupt metamorphoses of events and actions similar to those likely to take place in dreams:

Living or dead, you pay your respects.

Age creeps up. But it cannot

tell you apart.

You hide behind a moth

making its finest mimicry,

sacrificing sleep for you.

That Oppenheim’s poems should have a strong oneiric flavor isn’t surprising when we consider that she was in the habit of transcribing and analyzing her dreams in detail. It’s possible that some of her poems were based on her dream journal and might reflect the images she set down there or the interpretations she worked out for them. Here she wasn’t influenced by the Surrealists’ unorthodox Freudianism but instead by Jung. Her works of visual art often drew on Jungian archetypes, and some of the images in her poems have an archetypal or mythical feeling as well. The beauty in the water, for example, recalls the enchantress figure in the lady-in-the-lake legend; the mysterious personage obliquely alluded to in “Of Blood and Blooms”–itself a title that seems to have surfaced from the unconscious’ hypothetical thesaurus of symbols—resembles the trickster who lures us into whatever scheme he’s perpetrating but can never be caught. Jung’s animus-anima theory also was important to Oppenheim’s thinking as an artist as well as to her self-conception; she is known to have rejected the description “feminine art” to represent what she did, and preferred instead to conceive of her art in terms of an androgynous creativity. Androgyny in fact shows up overtly as a theme in the long prose poem “As though awake while asleep seeing hearing,” which reads like a dream transcription. The protagonist, a male character named Astor, undergoes a series of strange adventures, falls asleep, and upon awakening finds in his pocket a “calling card, printed with his new name: Caroline.” It’s tempting to read the poem as describing a journey into the male unconscious and the discovery there of the anima.

Heil translates from Oppenheim’s German into English with a sensitivity to the differences between the way the two languages convey distinctions of meaning, and to the particular way that Oppenheim played with invented words—easier to do in German, where new coinages of compound nouns are more readily admitted than in English—, homonyms, and words linked by the likenesses of their sounds. As she acknowledges, her translations involve “transformations” that seek to create a similarity of effect rather than a literal equivalence of meaning. Sometimes this shows itself as a conservation of the rhythm of a line, or in choosing words that offer near-rhymes of the original or approximate Oppenheim’s own rhyme scheme, or in the creation of neologisms in the spirit of German’s run-on nouns. The results read well. Happily, this edition is bilingual—trilingual in the case of the French poems—and so the reader can have the added pleasure of seeing the original alongside the translation.

The final poem in the collection, “Self-Portrait from 50,000 BC to X,” written in 1980 and the last poem Oppenheim is known to have composed, provides a fitting image for the rediscovery of Oppenheim’s poetry that this collection represents. It concludes:

…thoughts disperse in the

universe, where they on other stars

live on.

With The Loveliest Vowel Empties, Heil ensures that Oppenheim’s thoughts, as dispersed in her poetry, live on.

The Loveliest Vowel Empties: Collected Poems on World Poetry Books →

◊

Daniel Barbiero is a double bassist, composer and writer in the Washington DC area. He writes on the art, music and literature of the classic avant-gardes of the 20th century and on contemporary work, and is the author of the essay collection As Within, So Without (Arteidolia Press, 2021).