Magnifying Fakes

Randee Silv

December 2013

Situation #1: Kligman’s Red, Black & Silver

Situation #2: 123 Frida Kahlo Replicas

Situation #3: Qian/Diaz/Rosales/Knoedler

A woman next to me did portraits of owners’ dogs while they waited on the West Broadway block where I was selling with a few other off the grid painters in what we called “The Invisible Room Gallery.” Dealers and collectors who weren’t uncomfortable with serious artists showing on the street did stop and talk.

It wasn’t until 2001, after the group Artists’ Response to Illegal State Tactics had filed five years of First Amendment lawsuits, that visual artists no longer needed a vending permit and were allotted 8 feet of sidewalk space. Neighborhood retail stores’ reactions varied. Some even installed enormous planters out in front. I knew envious jewelry vendors who had to hire disabled veterans exempt from the city regulations.

To avoid fighting over a particular spot, you had to be out before dawn. Some slept in their cars and others would post threatening signs. By mid morning, weekend bargain hunters could leaf through bins of NYC tourist photos, cute animal and flower watercolors, xeroxed prints from art books, paintings of typical city scenes, uneventful landscapes and abstractions, oversized cartoon characters or dazzling ladies. The ones that could be easily rolled up were perfect for travelers. Everybody had a different approach to landing a sale. Your take by nightfall was always very secretive. No one wanted to admit if they’d had a zero day.

The Rosales/Knoedler forgery scandal, where an Asian immigrant street artist was cleverly maneuvered into an $80 million art scam, continues to make headlines. This lasted for 15 years until lawsuits were filed for reimbursements and damages.

“It’s like a joke on the world of art. Here I am dealing with the Knoedler gallery, one of the most prestigious galleries in the U.S., founded before the Metropolitan Museum of Art. If this person was selling these things on the street, we wouldn’t buy it. But this is the Knoedler gallery.” John Howard, Irving Place Capital CEO and former senior managing director of Bear Stearns, was fooled by a 1950s Willem de Kooning and is counting on a $3.5 million refund. Rosales had sold it to the gallery for $750,000.

Studying at the Art Students League in the early 90s, while working as a janitor and feeling discouraged about his career, Pei-Shen Qian set up a spot near West Fourth Street, where easels lined up with pretty impressive examples. Portraits of passerbyers were drawn late into the night. There were police sweeps and the money was sparse.

It looked like Qian’s luck was changing when he was offered $200 from a passing admirer to paint an imitation Ab-Ex painting. His patron was the art dealer José Carlos Bergantiños-Diaz, Glafira Rosales’ partner. Qian’s wife and child had arrived in the States. He’d been granted US citizenship and had bought a house. Diaz offered to represent Qian, who wanted to succeed through his own art.

Qian’s work was shown in Syracuse’s 1987 Community Folk Art Gallery exhibition, The Asian Dimension: Six Asian-American Artists. Lorraine Huang, guest curator, wrote in the catalog, “This art reflects none of the despair, anger and alienation found in much of contemporary Western painting. Could it be that the Asian cultures, having survived for so long, have bestowed a sense of balance and self-control that will help shape the future of the art world?” Qian also showed in Chinatown with Ai WeiWei in the 90s, in the 2008 Shanghai Zendai Museum of Modern Art exhibition, Turn to Abstract: Retrospective of Shanghai Experimental Art from 1976-1985 and last May in an exhibition at The Xiang Jiang Gallery in Shanghai. He is presently represented by the BB Gallery in Beijing.

He knew that he could never capture the “aura” of the Abstract Expressionist painters, that fire in layers of stroke rhythms, silences, lived moments. “It’s impossible to imitate them—from the papers to the paint to the composition. It’s impossible to do it exactly.” He could only paint “in the style of” Jackson Pollock, Willem de Kooning, Robert Motherwell, Clyfford Still, Barnett Newman, Sam Francis, Lee Krasner, Franz Kline or Mark Rothko.

It was these artists on the edge, the “American painters,” not the “gild-edged” or “blue chip,” that Fortune Magazine had already tipped off its readers about in December 1955. A “tryo collector,” wanting to buy in on the future boom of contemporary art investments, could have a de Kooning, Rothko or Pollock for only $500-$3,500. According to Qian, Diaz and Rosales never paid him more than $3000 for each counterfeit he supplied and told him that he was helping out buyers who couldn’t afford current market prices.

Neighbors reported that they would see a man picking up paintings from Qian’s garage. The court papers specified that Diaz aged these paintings by “heating them, cooling them, and exposing them to the elements outdoors, in an attempt to make the fake works seem older than, in fact, they were.” He might also have been the one who added signatures to over 60 fabrications.

Of course, I’m curious if Rosales and Diaz happened to know Ely Sakhai, the New York art dealer and gallerist who lived in a nearby Long Island town. Sakhai built up his capital dealing antiques and figured out how to sell fake Tiffany lamps. At the auction houses, he initially appeared in a purple suit and cowboy hat. He began purchasing lesser known Impressionist & Post Impressionist paintings that he would cleverly use as models for his copies instead of photographs. During the 90s, he recruited Chinese immigrants who had been professionally trained in copying masters and willing to keep quiet as they went along with his art forgery scheme.

Sakhai prepared the tea stained canvases with antique nails on stretchers from old, insignificant paintings. Then he would stand over his artists to make sure that they captured the exact brushstrokes and tiniest details. By 2000, ten or more artists were producing multiple copies of each painting in his gallery’s upstairs studio near Union Square. To secure the sale, the real certificate of authenticity was affixed to the fake. He knew he could easily apply for new ones.

Staying clear of the local authorities, he targeted the hungry and naive Tokyo art market, aware that a buyer’s embarrassment could work as protection. 200 flooded the market. One collector bought 17 worthless forgeries. Sakhai was making a fortune. The fakes went to Asia and the originals sold in New York. That was until Gauguin’s Vase de Fleurs was listed in both Christie’s and Sotheby’s catalogues. Christie’s had the fake.

For a forger to pull off a similar scheme today, he’d have to avoid the auction houses altogether, and do everything extremely quietly, through private dealers. Or, like a few great forgers of the past, he’d need to invent “lost” works from scratch, in the style of great artists, with no originals to trip things up—requiring the rare, talented painter who can pull it off wrote Clive Thompson in How to Make a Fake for New York Magazine after Sakhai was arrested in 2004.

Rosales’ strategy was to target someone with art world stature. At a cocktail party, she was introduced to the director of Knoedler Gallery, Ann Freedman. Knowing she had no convincing proofs of authenticity, Rosales gave a cover story about a Mexican art collector, whose name she couldn’t reveal, who’d bought these works in the 50s and hid the collection away in a container. After his death, the son, who was a personal friend of hers and uninterested in art, contacted Rosales. Rumored stories around their identities circulated. “Don’t kill the goose that’s laying the golden egg.” was Rosales’ response when pushed to name him, according to Freedman’s lawyer. Though, Rosales did reassure Freedman that “Mr. X Jr.” was happy with what she was doing.

The gallery had been advised by the Diebenkorn Foundation in 1993 that the drawings they’d been shown from the Ocean Park series were questionable and without records. One is in the Kemper Museum of Contemporary Art in Kansas City. Another was purchased by Freedman’s physician, who resold it.

In 2002, the International Foundation for Art Research could not verify the Pollock 1949 Untitled after Jack Levy of Goldman Sachs had requested confirmation of its authenticity. After his $2 million was refunded, Freedman bought it herself in partnership with art dealer, David Mirvish. He invited Frank Stella for his opinion on the Rosales collection. Freedman testified in 2006 that Stella had commented, “Each one is too good to be true, but seeing them in context, as a group, makes one realize they are true.”

Freedman went ahead and contacted the Dedalus Foundation, founded in 1981 by Robert Motherwell, to view a painting to be considered for the catalogue raisonné. Rosales had sold seven unknowns from the series Elegy to the Spanish Republic to Freedman and gallerist Julian Weissman. Jack Flam, the foundation’s president, was suspicious. Motherwell’s personal assistant was not. Flam hired a private detective to investigate Rosales and Diaz. Forensic results indicated that the pigments used had not yet been developed by the 50s. The FBI began an investigation.

I’ve read that John Howard had asked Freedman to keep her eyes open for a small rare Motherwell in 2007. She doubted she’d ever see one, but six months later, she did. Paintings seemed to pop up like this. Howard decided not to buy. A Kuwaiti collector sued Weissman over a $3 million Motherwell she’d bought. An art dealer from Ireland demanded a $650,000 refund for his. That painting was afterwards officially stamped with “Forgery” on the back. Freedman left Knoedler to open her own Upper East Side gallery.

Pierre Lagrange, a hedge fund manager from London learned in 2011 that he needed proof of authenticity to sell his 1950 Pollock Untitled through Sotheby’s. All he had was Freedman’s word that this was a lost work that had since re-emerged and her reassurance that it would soon appear in the catalogue raisonné supplement. Through forensic testing, Lagrange found out that the yellow pigments used had not become available until after Pollock’s death. He threatened legal action if his $15.3 million was not returned. Rosales had sold it to the gallery for $950,000. Freedman thought he should just find a new buyer. “You can’t sell it pretending there’s no problem. Even if I get my money back, it’s completely unfair to the other collector. And in the end I’m going to get sued.” was his response.

Knoedler was closing its doors. Domenico De Sole, a former Gucci executive, sued for an $8.3 million Rothko that Knoedler had marked up by 773% in 2004. The “sales pitch” he was given was that the painting had been purchased directly from Rothko by the painter’s personal friend, the art dealer David Herbert. Martin Cohen is also suing them for a Rothko along with a de Kooning painted by yet another forger, Tony Masaccio. The Manny Silverman Gallery is suing over a Clyfford Still. Cases keep surfacing.

Peter Schjeldahl offers a definition of fake in his November 2013 New Yorker Magazine article:

Fakes are contemporary portraits of past styles. No great talent is required, just a modicum of handiness and some art-critical acuity. A forger needn’t master the original artist’s skill, only the look of it. Indeed, especially in a freewheeling mode like Abstract Expressionism, a bit of awkwardness, incidental to the branded appearance, may impress a smitten chump as a marker of sincerity—even as something new and endearing about a beloved master.

Rosales pleaded guilty in September and has been charged with fraud, tax evasion and money laundering. Diaz has left the country with a tainted reputation following him. An ‘82 Basquiat that he’d left on consignment at Christie’s was bought by art dealer Tony Sharfazi in 1990 and sold to a collector, who, eventually learning it wasn’t authentic, sued Christie’s in 2011. Ann Freedman, Julian Weissman and Knoedler’s owner Michael Hammer claim to be victims.The Queens painter, now 73, has not been charged. He told the press in a recent interview, “I made a knife to cut fruit. But if others use it to kill, blaming me is unfair.” He doesn’t see himself as a crook. He wasn’t the one passing them off without provenance as recently discovered masterpieces. Qian was convinced that “Nobody would take them seriously.” But they did.

Knoedler Gallery, circa 1890, 170 Fifth Ave. NYC, photo: Getty Research Institute

Pei-Shen Qian in studio, photo: The Art Newspaper

Jackson Pollock: FAKE, photo: Art Market Monitor

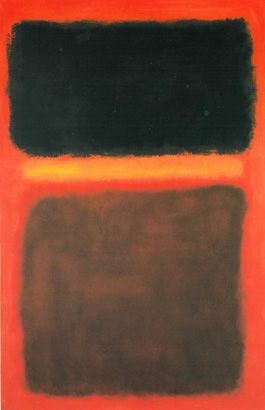

Mark Rothko: FAKE, photo: New York Daily News

Pei-Shen Qian, Night, 2011, photo: The Art Newspaper

Situation #1: Kligman’s Red, Black & Silver

Situation #2: 123 Frida Kahlo Replicas

Situation #3: Qian/Diaz/Rosales/Knoedler