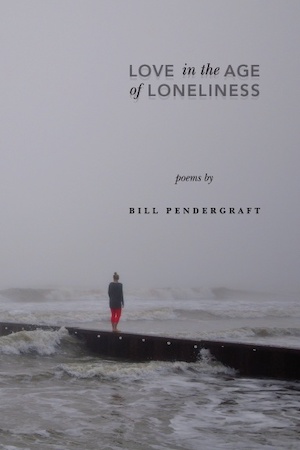

Love in the Age of Loneliness

January 2025

Daniel Barbiero

In the Preface to Love in the Age of Loneliness, his new collection of poetry, Bill Pendergraft quotes evolutionary biologist E. O. Wilson to the effect that the human predicament peculiar to the present age is the product of our having “Paleolithic emotions, medieval institutions, and god-like technology.” There is a misfit between our evolutionary inheritance and the artificial environments we’ve created for ourselves, and the threat of a profound isolation is the result. Pendergraft’s poetry addresses this predicament and suggests that by reestablishing a link with the natural forms of life around us – including our own — we can find a way out.

The “Age of Loneliness” of the collection’s title is a translation of what Wilson called the epoch of the Eremocene. “Eremocene” derives from the Greek “eremos,” meaning loneliness, or desolation. For Wilson, the loss of ecosystem diversity, the rise of mass extinctions, and the consequent shrinking of the biosphere – all of these from the pressure of human activity – create not only environmental desolation, but condemn humans to a state of existential solipsism in which other forms of life have disappeared.

The poem “Eremocene” takes Wilson’s idea and brings it to life through the witness of a single person:

as a child

grandfather paddled the salt marshes

called the marsh sparrows and wrens

who climbed the spartina to seewhen he retired from machines

he flew home

marshes mitigated by interstates

spartina smothered in spoils

children following the money

Pendergraft takes the macrocosmic trend of human encroachment on the natural world and reduces it to the microcosmic particulars of change observed over a single lifetime. The birds and marsh grass of the grandfather’s childhood are “smothered” under the artifacts of industrial development to which he, as a worker with machines has, wittingly or not, contributed; a younger generation chooses to chase the fruits of economic growth, thus contributing to a further expansion of the human footprint and shrinking of the biome. Hence the spiral of activity through which the conditions making an Eremocene epoch possible are perpetuated and deepened.

The antidote to the solipsism of the Eremocene is a reengagement with nature. For Pendergraft, this entails the close observation of the biota wherever he happens to find himself. A haibun titled “The Preacher” tells of his experience living alone in the forest in the northeastern corner of Vermont; the call of a red-eyed vireo, the bird of the poem’s title, reminds him “to pay attention.” The brief poem at the close of the haibun, a haiku in perfect 5-7-5 syllable form, records the circumstance that makes such attention necessary:

summers in the beech

our natural companions

fewer voices heard

Pendergraft’s attentiveness is embodied in “May in Vermont,” a poem full of the precise details of spring in a New England deciduous forest. The vividness of the scene is enhanced by Pendergraft’s exclusive use of the present tense (“scattered” reads as an adjective) and telegraphic syntax; even the allusion to Whitman doesn’t take away from the immediacy of what appears:

peonies poke red heads through the clay

lilacs last in the dooryard bloomrhododendron leaves curl under in a late freeze

red oak’s hard cautious buds

confident apples fully leaf out

red trillium scattered by the vernal pool

With the exception of the psychologizing “confident” to describe the apple trees’ coming into leaf, the scene is presented objectively and seemingly without comment or judgment. Nothing of the speaker’s personality is brought explicitly into it, but this reticence seems to be the product of a modest respect rather than an emotional detachment. Given Love in the Age of Loneliness’ overall theme of the eclipse of the natural world by human activity, a note of irony does emerge at the end, as the poem records the reencroachment of nature on the human world:

the vireo’s constant song

the ladybugs in the windows

ants in the honey bowl

mice in the cellar hole

“May in Vermont” is a reminder that even for those of us in First World, post-industrial societies, for whom much of our daily experience is mediated through digital texts and images, nature retains its power to compel our attention. What Pendergraft seems to imply is that, with the kind of observation recorded in this poem – observation as a form of being-with, I’d like to say, a way of letting beings be by recognizing their right to be — we can reestablish a connection with nature as an event in which we are always already involved as interested participants. If we allow it to, it can tell us not only where we are but what we are and what concerns – our should concern – us. It’s the antithesis of the solipsism of the Eremocene.

“May in Vermont” was written from Pendergraft’s home region. Other poems in the collection were drawn from diaries he kept while traveling throughout the world as a producer of educational materials on the environment for a variety of institutions and outlets. There are poems not only from the natural environment, but from cities as well: New York, Chicago, Washington. There is a harrowing poem on a fire in Marfa, Texas, and the awful fate it brings to animals as the local news media look on:

cattle horses antelope pigs

ran before it

their eyes wide and wheeling

tongues bleat and slobber

blackening among the dry beds

smelling for water gone

escaping toward the highway

tangled in barbed wire

writhing and boiling in the flame

cooking on the stone and bramble

among news trucks from Austin

Throughout the book we meet a number of different people whom Pendergraft presents in sympathetic vignettes. Most poignant are the old men marked by the effects of time and work, remembering and forgetting. There is “Robert who runs a little/ crab boat out of Lucy creek/ across St. Helena Sound” and whom the sea has “worn” and made “storm tossed, shot, spent”; there is “The Old Man on the Beach,” “waves of recollection/ rolling up to his toes/ as he stands in the wrack/ expecting sunrise”, and whose recollection of the touch of another lets him “for a moment” be “a believer/ in just one more day”; there is the man who collected marbles for eighty years and is now “wondering where they all were/ like his penciled notes piled around the cottage/ grocery lists—names of doctors/ phone numbers of his children gone-forgotten.” The ambiguity of this last line makes us wonder what is gone and forgotten – is it the children? Or only their phone numbers? Contrasting with these weathered men is “The Young Immigrant Sanding Sheetrock” who pointedly asks:

do you think because you noticed

and wrote a poem

that anything is better

The speaker’s reproach is left hanging at the end of the poem, and I can’t help but wonder if this is an indirect expression of self-doubt on the part of the poet, a suspicion that poetry just isn’t enough. But poetry is a form of memory, and if one believes that the world or parts of it are about to disappear, then wouldn’t noticing them and preserving them in words be something better – better than forgetting, better than nothing?

What poetry can remember is the multimodal, sensual pleasure of being in a complex world. It’s a pleasure Pendergraft captures throughout the book. To that point, “Each Day Yawns Open” is as good a way as any to let him have the last word:

all day I fill the basket

a ripe tomato in my hand

warm green peppers in late sun

leeks pulled from black earth

the song of warblers home

children along the porch

careless-forgiven-almost forgotten

the wind licks up salt with sunfall

we taste it on our lips

sleep in fecund joy

Bill Pendergraft: Love in the Age of Loneliness

Environmental Media, 2024

For more information on Love in the Age of Loneliness →

Daniel Barbiero is a double bassist, composer and writer in the Washington DC area. He writes on the art, music and literature of the classic avant-gardes of the 20th century and on contemporary work, and is the author of the essay collection As Within, So Without (Arteidolia Press, 2021).

Link to Daniel Barbiero’s, As Within, so Without →