Lost & Found: The Missing Pieces

Daniel Barbiero

February 2025

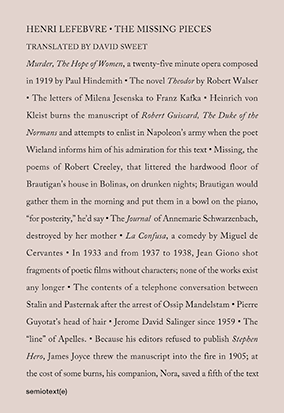

The Missing Pieces

by Henri Lefebvre

translated by David Sweet

SEMIOTEXT(E)

There’s a scene in Dubravka Ugrešić’s comic novel Fording the Stream of Consciousness where Jean-Paul Flagus, a French writer, entertains a group of his fellow writers at an international conference by recounting incidents of literary works being lost or destroyed due to domestic disasters: John Warburton’s cook burning or lining cake tins with Warburton’s collection of Elizabethan and Jacobean drama manuscripts; Sir Richard Burton’s wife Isabel burning Burton’s translation of the Kama Sutra; William Ainsworth’s enraged wife throwing Ainsworth’s Latin dictionary into the fire; Isaac Newton’s dog overturning a candle and burning a number of Newton’s papers; John Steinbeck’s dog tearing up an early version of Of Mice and Men. The lost work is an artist’s nightmare, to be sure, but it’s a phenomenon that recurs throughout cultural history, which it leaves full of holes.

Consider these:

Murder, the Hope of Women, a twenty-five minute opera composed in 1919 by Paul Hindemith • The contents of a telephone conversation between Stalin and Pasternak after the arrest of Osip Mandelstam • Pierre Guyotat’s head of hair • In 1917, Leos Janácek decided to write The Diary of One Who Disappeared based on an anonymous text • On the Road: the final seven meters of Jack Kerouac’s original typescript were eaten by a dog • Influential surrealist “poet” Jacques Vaché never wrote a thing • In Vladivostok, the city where Osip Mandelstam is said to have died (no one is sure of this), a cast-iron statue representing the poet was lost, a victim of metal looters • There are only three words remaining of the Cumbrian language, which was related to Gaelic and disappeared around the seventh century CE (Jacques Robaud will compose some poems using the last three remaining words • We no longer know why Henri Lefebvre fell out with Guy Debord • The library at Alexandria in 47 BCE • Net Art: any work of virtual art is hereby condemned to disappear • In 1970, Robert Filliou offers Bengt Adlers the drawing Meditation Bound, representing three men with closed eyes; after Filliou’s death, the central figure mysteriously disappears from the drawing • In the eighties, sculptor Jacques Lélut was commissioned by the French National Agency for the Recovery and Disposal of Waste to create four statues representing Earth, Air, Water and Fire; Earth and Air ended up in a dump, Fire was stolen, while Water, placed near the elevators on the third floor of the Ministry of Ecology and Sustainable Development, had its tuba stolen • Hans Christian Andersen, who worked as a singer, loses his voice; he starts writing • Goethe, lost orthographic ability; Dostoyevsky, lost syntactic ability • The indigenous art of all epochs destroyed by missionaries •

Cultural history—Western cultural history, for the most part—as a lacuna-filled story of absences due to loss, is the theme of Henri Lefebvre’s The Missing Pieces, from which the above excerpt was taken. Lefebvre, a contemporary French poet not to be confused with the twentieth century Marxist sociologist of the same name, has constructed a sui generis text made up of a deadpan inventory of several hundred items — works that were destroyed, lost, suppressed, or never made; of ideas that went unrealized; of people and information gone missing: of empty spaces where something was, or should have or would have been. It is a catalogue that memorializes what has, for whatever reason, disappeared.

And there are many reasons. In The Missing Pieces what’s missing is missing from a variety of causes natural and artificial, public and private: war (“The great university library at Louvain, destroyed in a fire in 1914, and the library of Sarajevo, bombarded in the winter of 1992-1993”); revolution (“The library of the Louvre, burned in 1871”); government repression (“In April 1936, the manuscripts of Victor Serge are confiscated on the orders of Stalin”); religious zealotry (“The great Buddhas of Bamiyan”); natural disaster (“The Acanthus Column, at Delphi, which supported the Omphalos (the navel of the world), is destroyed in 373 BCE during an earthquake”); ignorance or misunderstanding (“The drawings on burnt paper by Patrick Neu were ‘vacuumed’ by the cleaning staff during the 2003 FIAC”); frustration (Meret Oppenheim, annoyed by the success of her Object, or Breakfast in Fur (1936), destroys all her works after the war”); forgetfulness (“Guillaume Apollinaire claims to have lost, on a train, the manuscript to his first novel, The Glory of the Olive”); destruction of the historical record in the service of self-mythologization (At twenty-nine, Sigmund Freud burns all of his manuscripts); heartbreak (In Madrid in 1927, Nancy Cunard breaks up with Louis Aragon; Aragon burned In Defense of the Infinite and attempted suicide”). Some of the losses are tragic, some are trivial, some were willed and others inadvertent, but all represent gaps in the collective memory that is a culture.

* * *

In giving us a counter-history of culture as analogous to a tissue left threadbare in many places, Lefebvre points up the peculiar role absence plays in how we remember ourselves. Memory, whether personal or collective, is notoriously unreliable and its unreliability isn’t helped by the disappearance of the evidence that could corroborate or correct it. What Lefebvre’s catalogue suggests is that we can think of collective memory as a grand Encyclopedia, and the missing pieces as its empty or incomplete entries and blank pages.

The metaphor of the Encyclopedia, which I borrow and adapt from Umberto Eco, lets us imagine the cultural record as a publicly registered, comprehensive reference work whose contents are exemplary of how a human group recognizes itself in the cultural products, projects, and ideas of its collective life. The Encyclopedia encompasses past history, present effort, and future possibility in both their positive and negative manifestations; it implies a claim to being comprehensive. But as Lefebvre’s The Missing Pieces shows, the Encyclopedia inevitably contains lacunae and a consequent instability. The past we think we know isn’t necessarily the past that was – gaps in the record make sure of that – while that same past is liable to change its meaning as previously lost or unknown pieces of it come to light. The past, like the future, is in its own way a field of possibility. The Encyclopedia is always subject to revision.

What Lefebvre’s catalogue dramatizes is that what makes it into the Encyclopedia – the supporting evidence as well as the content of its entries – is contingent on the whims of circumstance. This is easiest to see when objects actually are lost or destroyed and information is missing. Paradoxically, though, some of Lefebvre’s items demonstrate that an empty or incomplete entry in the Encyclopedia isn’t an effect of a lack of evidence, but on the contrary, of a surfeit. We often find multiple and contradictory versions of what pieces are missing, or why.

For example, Lefebvre cites the “fact” that the final bit of the typescript scroll of On the Road was eaten by a dog. (According to Kerouac’s note on the scroll, the culprit was Lucian Carr’s dog, Potchky). That’s one story, but there were others – that Kerouac didn’t like the original ending and tore it off; that Kerouac never really had an ending to begin with. The eaten-by-a-dog story recalls the stereotypical excuse used by a child to explain missing homework – “the dog ate it!” Was Kerouac’s note a joking play on that excuse? The faithful report of a fact? In the end, we really don’t know what happened or why, although we do know that the typescript is missing a conclusion.

On a far less amusing note, there’s Stalin’s June 1934 phone call to Boris Pasternak regarding the recently arrested poet Osip Mandelshtam. As the Albanian writer Ismail Kadare has shown, there are at least twelve accounts of what was said, recorded not only in the KGB archives, but in memoirs, diaries, and oral recollections. We have some idea of what was said – Stalin seems to have wanted to get Pasternak to defend Mandelshtam as a master poet, and Pasternak equivocated – but the details vary, sometimes substantially. Disentangling what really was said during that two- or three-minute call at this point is impossible. We can imagine that in the Encyclopedia, the entry on Stalin’s phone call to Pasternak would consist of the printed equivalent of garbled crosstalk: an illegible block of superimposed words. (As for Mandelshtam himself, he endured a triple disappearance: into the Gulag system and from life, and then from material memory with the destruction of his statue, its perpetrators unknown. But at least we seem to know when, how, and where he died. His death certificate, dated 27 Dec 1938, gives the cause of death as heart failure and the location as Vladivostok Transit Point – a secret camp near Vtoraya Rechka railroad station.)

In some cases, the empty or incomplete entry in the Encyclopedia is the result of the complexity and opacity of human motivation. Take, for example, Lefebvre’s witty reference to the other Henri Lefebvre: “We no longer know why Henri Lefebvre fell out with Guy Debord.” To be sure, we do have an idea, at least from Lefebvre’s side of the break, as he recalled it to Kristin Ross in a 1983 interview. The circumstances were complicated and seem to have involved a dispute over the authorship of a text on the Paris Commune as well as Debord’s purported interference in one of Lefebvre’s personal relationships. There doesn’t seem to have been a single cause, and to the extent that the falling-out consequently was overdetermined it’s possible to say that we don’t know what “really” was at issue. Lefebvre himself said that he didn’t understand it too well himself, and it’s possible that that may reflect something of the ambiguity of memory in which affect interferes with, and potentially distorts, the recollection of fact. As with the case of Stalin’s phone call, Lefebvre’s uncertainty recalls Nietzsche’s dictum that there are no facts, only interpretations – and sometimes wobbly ones at that.

* * *

The Missing Pieces has been described as a prose poem. Given its unorthodox form, we might well wonder where the poetry is. I would suggest that it doesn’t consist in any formal features, but rather in the cumulative force of its content. In short, the poetry of The Missing Pieces is the poetry of what isn’t – of absence.

Absence is fascinating for what it seems to withhold from us. It teases us with the possibility that what it withholds is the lost key, the missing clue or vital piece of information needed to make sense of whatever it is that lacks it. Without it, the record is compromised and unreadable, and its not being there throws a shadow over what is and puts its value and veracity into question. It’s a nothing that nevertheless manages to be the center of attention precisely by virtue of being a nothing. I’m reminded of the set-piece in Being and Nothingness in which Sartre describes the non-appearance of someone he expects to see at a café at a certain time: that person’s absence is the defining fact through which the café is experienced — as a field haunted by the absent figure that should be at its center, but isn’t. In manifesting itself as a negated expectation, absence ironically makes itself present, seemingly to the exclusion of all else.

In a larger sense, absence as such is an inevitable factor in our encounter with the world. It’s a reminder that our knowledge is always provisional, partial – in both senses of being incomplete and colored by our concerns or interested precommitments – and the product of, as well as given to, a point of view reflecting the finite nature of our own situation. Absence reveals the limitations of what we can know by revealing to us our own limitations, in other words. Our way of being in the world guarantees that there always will be missing pieces. It’s a poetic truth that The Missing Pieces recalls with each of its anecdotes.

* * *

The central paradox of absence is that what’s missing often implies what could have been there. This is just another way that absence shows itself as a negated expectation. The missing thing carries an intimation of a counterfactual world, a world that would have existed had it been completed by the existence of these non-existent things. That these things (ideas, bits of information, people) aren’t here is an indication that they should be here. Their nonexistence is a tacit acknowledgment of the possibility of their existence: if not for the latter we wouldn’t think of them in terms of an absence but rather as simple non-existence. Absence implies that there was something there, or that there should’ve been something there, but that there isn’t. Our expectation is negated, but in being negated it pushes us to attempt to articulate what had been there, or to hypothesize what should have been there; in the attempt, we manifest a natural urge to negate that negation. It’s as if the lacuna opened up by the missing piece is a white screen waiting to have something projected onto it. At times this projection goes beyond a simple “what-if” thought experiment. For example, two of the unfinished works Lefebvre includes in his catalogue – Mahler’s Tenth Symphony and Modest Mussorgsky’s opera Khovanshchina – subsequently were completed in different versions by different composers. Both have even been performed and recorded.

* * *

To be sure, Lefebvre’s catalogue of the lost is a reminder that the content and comprehensiveness of the cultural record – the Encyclopedia – is subject to the whims of accident. But accident works both ways, and “missing” doesn’t necessarily mean non-existent. There are cases in which the counterfactual history suggested by the missing pieces becomes factual history as some of those pieces fall into place, and empty entries in the Encyclopedia are filled in. This is true of some of the missing pieces in Lefebvre’s catalogue, as he notes in a brief remark after the main text. Unfortunately, he doesn’t say which. But we can imagine what the reverse side of the coin of which Missing Pieces is the obverse, would look like:

The phonetic values of Egyptian hieroglyphs, partly discovered by Thomas Young around 1814 and more fully worked out and tabulated by Jean-François Champollion in 1822 • The 1950 “Joan Anderson Letter” from Neal Cassady to Jack Kerouac is loaned out to Allen Ginsburg in the hope of finding a publisher for it and is presumed lost over the side of Gerd Stern’s houseboat shortly thereafter. The letter is found in an attic in a box of rejected material from the archive of a defunct publisher in May 2012 • Vincent van Gogh’s 1888 painting Sunset at Mount Majour, discovered in an attic in Norway in 2013 • A large fragment of Sophocles’ satyr play Ichneutae is retrieved from the site of an ancient trash dump in Oxyrhinchus in Egypt, circa 1896 • Jazz bassist Henry Grimes, disappeared from New York in the late 1960s and found in Los Angeles in 2002 • A trove of artworks by Jackson Pollock, Kenneth Noland, Jules Olitski, and Cora Kelley Ward is discovered during the clean-out of a garage in Sun City, Arizona, in December 2015 • In 1961, Belgian Egyptologist Herman De Meulenaere discovers that the Brooklyn Museum’s head from a 4th century BCE statue of Egyptian official Wesirwer belongs to a torso in the Egyptian Museum in Cairo; in 1962 the head and torso are reunited for a temporary exhibit in Brooklyn, making it the first time in over two thousand years that the statue has been seen in one piece • Percy Bysshe Shelley’s poem “Poetical Essay on the Existing State of Things” is written as an undergraduate at Oxford in 1810-1811 and published as a pamphlet, all copies of which were thought to be lost; one is discovered in 2006 • On the Shore of the Seine, a small landscape by Renoir apparently stolen from the Baltimore Museum of Art in November 1951, turns up at a flea market in West Virginia in 2012 where it is purchased for $7 • Antonín Dvořák’s Symphony No. 1 in C Minor, is composed in 1865 and claimed by Dvořák to have been destroyed. The manuscript is purchased by a Rudolf Dvořák (no relation to the composer) in the 1880s, its existence is announced in 1923, and the work is premiered in 1936 • North Carolina painter Beth Feeback purchases an abstract painting from a Goodwill store for $9.99 in order to reuse the canvas for a cat portrait she will paint over it; the painting is determined to be Russian-American abstractionist Ilya Bolotwsky’s Vertical Diamond, which subsequently sells for $27,000

What’s clear is that the circumstances under which lost works are found aren’t any less arbitrary and absurd than those under which they can be lost, and that the Encyclopedia, like many of the items in Lefebvre’s catalogue, must remain perpetually unfinished.

References:

Umberto Eco, Kant and the Platypus, tr. Alastair McEwen (San Diego: Harcourt, 1997).

Ismail Kadare, A Dictator Calls, tr. John Hodgson Harvill (Brooklyn, NY: Counterpoint Press, 2023).

Henri Lefebvre, The Missing Pieces, tr. David L. Sweet (South Pasadena, CA: Semiotext(e), 2014).

Kristin Ross, “Henri Lefebvre on the Situationist International” (an interview conducted and translated in 1983, originally appearing in October No. 79, Winter 1997). Accessed at https://www.notbored.org/lefebvre-interview.html

Jean-Paul Sartre, Being and Nothingness, tr. Sarah Richmond (New York: Washington Square/Atria, 2018).

Dubravka Ugrešić, Fording the Stream of Consciousness, tr. Michael Henry Heim (Evanston, IL: Northwestern U Press, 1993).

For more information on The Missing Pieces by Henri Lefebvre →

Daniel Barbiero is a double bassist, composer and writer in the Washington DC area. He writes on the art, music and literature of the classic avant-gardes of the 20th century and on contemporary work, and is the author of the essay collection As Within, So Without (Arteidolia Press, 2021).

Link to Daniel Barbiero’s, As Within, so Without →