Jeanne Liotta: The World is a Picture of the World

Franziska Lamprecht

October 2021

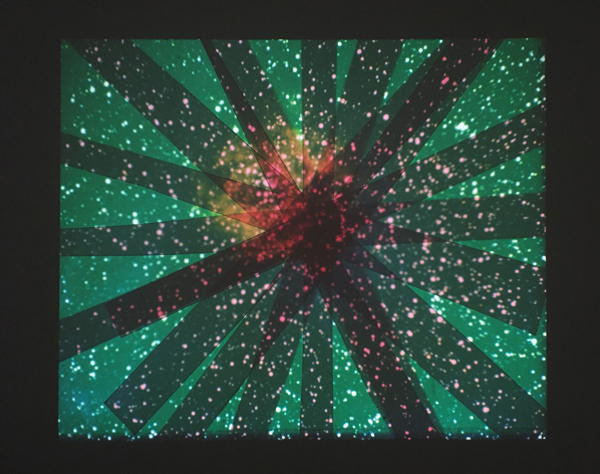

Jeanne Liotta, “My Mind of Universes Erupting Continuously,”

Jeanne Liotta, “My Mind of Universes Erupting Continuously,”

2021, 80 handmade 35mm slide projection, installation view

— Courtesy of the artist and the Microscope Gallery

Whoever climbs the narrow, grey stairs and enters the dim gallery space on the second floor on 29th street, will be met by the workings of four small compact machines that devoted most of their working life-time to the formal classroom education of humans who used them to learn about history, science and the universe. Standing on long thin metal legs, the bodies of these apparatuses embody the fact, that we always had a very specific viewing history, and that it has always been our assigned use of technology that shapes the way we perceive and imagine the universe.

“This then, I thought, as I looked round about me, is the representation of history. It requires a falsification of perspective. We, the survivors, see everything from above, see everything at once, and still we do not know how it was.”— W.G. Sebald, The Rings of Saturn

Parts of this history, which might have been very hot and agitated in the day when it was called present, are cooled in the gallery by an industrial humming sound; four built in fans are continuously blowing to prevent the melting of thin plastic or the start of a fire. Then there is the clicking of the carousel, a simple mechanism that stoically pushes a 35mm piece of exposed film in a cardboard frame in front of a light bulb. Like Phileas Fogg, who 150 years ago traveled “Around the World in Eighty Days,” eighty of those slides are continually moving forward in a rotating fashion, following mechanically set reoccurrences and therewith, their own path of decay through exposure to light.

I asked Jeanne Liotta, who titled her show: The World is a Picture of the World why lenses are round and not rectangular, like the images we see on the wall. Do lenses imitate our eyeballs? “No,” Jeanne said, “they more likely imitate the power of magnification that comes with every single drop of water that lives on the surface of a leaf or a windshield.”

I tell her about the big raindrop I once saw. It hung on a small branch on a rainy day, that spread nothing else but foggy grey and therefore challenged me, I guess, to find something that offered a hint of sparkle. I went on a walk, and there it was: the wonder of the shiny raindrop hanging on a random branch, which contained everything around me; the forest, the sky, the brown leaves on the ground, the very pale sun, it even included me. I was inside the raindrop, inside the forest. I waved and my miniature distorted self waved back. I was in awe. When I stepped back and suddenly realized, that there was not just one raindrop, but hundreds of them hanging on the branches of that bush, and that there was not just one bush, but hundreds of them in that forest I was in, I got a glimpse of what people who looked through powerful telescopes may call infinity. I tried to take a picture of the universe inside the raindrop with my phone. It came out very blurry. Was that real? I ask Jeanne.

— Courtesy of the artist and the Microscope Gallery

— Courtesy of the artist and the Microscope Gallery

“I am thinking about any persons’ desire to see the invisible, the marginal, the infinitesimal, and the distant, the dimensional field of all our lives. Where does the imagination meet the document, the photograph, the supposed real…” Jeanne said.

The wondrous joy of being able to become alive within the cosmos of a raindrop came back to me watching Jeanne’s slideshow. She had found a way to capture her version of that miracle in the never ending rotation of 80 green tinted slides, that when projected on the wall, showed overlapping circles and discs, some with clearly defined edges, and some with fuzzy outlines augmenting educational NASA photographs that depicted the surface of the moon or the fragile blue marble we call home as last seen by human eyes in 1971 from outer space. Jeanne had bought a set of these educational slides off ebay and one day she took one of them out of their little box and put it in her studio’s window in Colorado. She wanted to look through a slide of the universe out into the world, not considering that she would be exposing the slide to constant sunlight. After a few months of Southern exposure the slide had turned green, which let Jeanne start to ponder: “Shall I put it into a dark place and rescue it, or shall I keep exposing it and let it go?”

She took it off the window and using transparent office tape, glued a small asteroid directly onto the slide. Then she turned the slide upside down, flipped it horizontally, put it into a slide projector and looked at that image of the earth that once was considered to be officially und unquestionably real, because in the 1970’s NASA had used the most advanced and accurate technologies to capture that realness. With a few overlapping strips of transparent tape, Jeanne had introduced a speculative pattern, a different way to visualize light rays, celestial paths and the endless possibilities that emerge when one does not only connect the dots, but moves them into new positions. She had disrupted and questioned a once approved reality, like a joyful, low tech version of Elon Musk, she had inserted her private space travel itinerary into the American space program, that used to be publically funded, existed outside of copyright and kept collective wonder and awe well nourished.

After she realized the effects the sun had on her first window slide, Jeanne kept more consciously collaborating with the sun. She invested in solar power, she let about 120 educational NASA slides soak up the light that would turn them green like a deep pond that was on the verge of being suffocated from algae. She kept experimenting. Small transparent stickers became new planetary bodies, half ripped paper trials looked like the moon had cracked, dropped its better half on the earth and was now in the process of growing new moon tissue.

Once in a while there appeared a black star with five points, the kind of star you would glue into your notebook as reward for having clearly sketched out the mystery of the universe in a diagram with overlapping lines and mathematically accurate curves. There was also dirt in some slides, parts of hair or fiber, floating around like the 27.000 pieces of orbital debris that are currently being tracked by the Department of Defense’s global Space Surveillance Network sensors.

When I learned that Jeanne was using her originals slide collages in the slide projector, I almost felt guilty for watching and I asked myself, if they were slowly burning up for no other reason but for me to be there and see. They were not there for me, of course, but nevertheless, every time a slide was shining big and beautiful against the wall, it was already a round older, it already had decayed a little bit further.

When we left the show together I told Jeanne, that I had grabbed the branch of the bush and shook it, until all the raindrops were gone. She said: “Yes, that same thing happened with my last show, which consisted only of projections. On the very last day, when I turned off the power, the veil of illusion lifted. Everything was gone.”

There are 14 more days in the calendar before that happens. The show closes on October 16th.

Jeanne Liotta

The World is a Picture of the World

September 9 – October 16, 2021

525 West 29th Street, 2nd Floor

New York, NY 10001

Artist Talk: Jeanne Liotta in conversation with Ed Halter →

Franziska Lamprecht is a visual artist who started writing as an extension of the long-term process based works, she produces together with Hajoe Moderegger under the name eteam. For their work they have received support from Creative Capital and The John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation, Art in General, NYSCA, NYFA, Rhizome, CLUI, Taipei Artist Village, Eyebeam, Smack Mellon, Yaddo and the MacDowell Colony, the City College of New York, the Hong Kong Baptist University and the Fulbright Foundation among many others.

In 2020 eteam published their novel: Grabeland with Nightboat Books. Franziska has written reviews for Full-Stop magazine, Bomb magazine and Dovetail Magazine.