Is Silence Golden?

Daniel Barbiero

January 2021

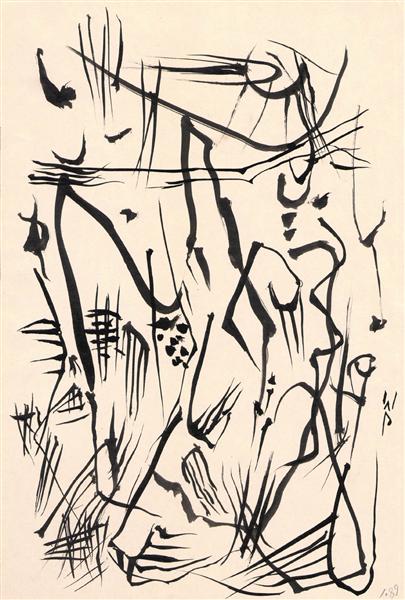

Untitled (Automatic Drawing), Wolfgang Paalen, 1950

Untitled (Automatic Drawing), Wolfgang Paalen, 1950

Either No Music, Or a “Return to Principles”

In 1944, “Silence Is Golden,” a somewhat curious article by André Breton, appeared in the March-April number of Modern Music. What was curious about it was just the fact that an article by Breton should appear in a music journal at all. Breton, the founder and longtime leader of the Surrealist movement who at that moment was enduring war-induced exile in New York, was notorious for his antipathy to music.

There was historical precedent for Breton’s attitude. Giorgio de Chirico’s 1913 statement “Point de musique” (“no music”), in which the painter declared that the visual imagery of painting was a kind of music of its own, may have set the pattern. Similarly Apollinaire, an early mentor of Breton’s, had a negative attitude toward music generally and contemporary music specifically, possibly having been influenced in that regard by Alberto Savinio—the musician/painter/writer brother of de Chirico. As for Breton himself, the rejection of music was at least partly explained by the fact that France’s emerging interwar avant-garde composers, Les Six, were part of the circle around Jean Cocteau, whom Breton detested: in “Silence Is Golden,” Breton quite candidly confesses that his dislike of music is related to his dislike of Cocteau. (This did not prevent one of the six, Georges Auric, from having been a friend of Breton’s and from having been briefly mentioned in the latter’s first Manifesto of Surrealism, although—eventually gravitating toward Cocteau–he never became a part of the Surrealist group.) Other personal reasons may have come into play as well. During the Dada period Breton had spoken well of composer Erik Satie, but the two fell out during the exchanges of vituperation surrounding the collapse of Breton’s plans for the Paris Congress of 1922.

Given this background, “Silence Is Golden” seems to represent an offer of détente rather than a continuation of hostilities on Breton’s part. It could be, as Breton lets on with elaborate politeness, that it would be bad form to disparage music in a journal dedicated to music—after all, one mustn’t insult one’s host, no matter what one really thinks of him or her. And the tone of the piece is shot through with ambivalence, which is only reinforced by the entanglements of Breton’s prose, the convoluted opacity of which seems to give evidence of an unwillingness to make a statement as explicit as the provocative title would seem to promise. (And the title itself must have struck the reader of Modern Music, as it just as easily can strike the reader today, as an arch commentary on Breton’s rejection of music—a homely cliché whose appearance in a music journal would unavoidably carry an ironic flourish which, in revealing Breton’s actual attitude toward music, rebounds back on itself in the double irony of stating the truth under ironic circumstances. Perhaps.)

Questions of tact having been raised and answered, Breton forthrightly acknowledges the “negative attitude aroused by instrumental music” among the Surrealists and more generally among artists whose medium is language. And he suggests that the musical properties of poetic language are a “compensation” for these artists’ rejection of music as such. Nevertheless, he holds out the possibility that the antinomy of poetry and music could be overcome through a “fusion” of verbal musicality and musical composition. Not to suggest how it could be overcome—Breton would give no specifics, modestly acknowledging his “complete ignorance” of compositional methods–but simply that it could be. Despite this diffidence, Breton offers a general program for composers—and it does seem clear that Breton is thinking of composers here and not performers—to pursue.

What Breton called for was a “return to principles” for music, through which hearing could be “reunified.” What he seems to have meant by this somewhat puzzling expression was that properly composed music could reconcile the contradiction he saw between perception and imagination: music returned to principles would resolve the opposition between the plain facts of sound picked up by the naked ear and the imaginative constructions through which those facts would be revealed to be the carriers of marvelous or portentous meaning. As with the Hegelian dialectic on which it was based, this reconciliation would take place on a higher plane—on the plane of an overarching super-reality or surreality, properly speaking. Breton’s advocacy regarding music is of a piece with the program he set himself from the inception of the Surrealist movement. The reunification of hearing that he called for was just one, medium-specific instance of the larger Surrealist project of reconciling the empirical reality of wakefulness and the imaginative reality of the dream in the higher synthesis of the surreal. And as with poetry and the other arts the Surrealists engaged in, music wouldn’t be an end in itself but rather a way of opening up a path to this higher reality—to what Breton in the Second Manifesto of Surrealism described as that “certain point of the mind at which life and death, the real and the imagined, past and future, the communicable and the incommunicable, high and low, cease to be perceived as contradictions.”

But Music Is Already Disruptive

Breton didn’t raise this possibility, specifics of musical composition being, as he admitted, beyond his understanding, but—reading between the lines, and knowing what we know about Surrealist method–could he be suggesting that composers engage in something analogous to the “pure psychic automatism” that, having been used to define Surrealism as early as in the first Manifesto, had always been the mainstay of Surrealist creative activity? He doesn’t say. But it nevertheless is worth asking: if music is to express an “inner music” comparable to that of poetry, how would it go about doing so? What, in other words, would be the compositional equivalent of automatism—or would there be? (And following Breton’s presumed focus on the work of composers, we will only consider composition here rather than performance. Thus the very interesting and valid question of improvised music and its possible relationship to Surrealism and Surrealist automatism must be left for another time.)

It’s difficult to see how composition could work on a model derived from automatic writing. As described in the first Manifesto, automatism, as the means through which one could record the “actual functioning of thought…in the absence of any control exercised by reason,” would require the composer to be reduced to something like the “modest recording instrument” Breton described the automatic writer as having become. Ideally on this model, he or she would be left to transcribe the uncanny associations and incongruous images inhabiting an otherwise submerged or unattended-to psychic reality (which we can think of as the unconscious as, under Freud’s influence Breton did, or simply as the unfettered play of the imagination). How to square the strictures of musical notation with the rapid, uncritical movement of the hand essential to automatic writing is by no means obvious.

(I leave out of consideration graphic scores, which could be created through means similar or identical to automatic drawing. But how much fidelity the performance of a graphic score would have to the psychic state that provoked its composition is an open question. It would seem that the degree of interpretation required of the performer would be sufficiently great as to dilute the capacity of the work as played to stand as the direct record of the composer’s unconscious impulses. On the other hand it may be that all that’s required of this type of compositional automatism is the production of the score, the performance representing an extension of the creative impulse automatism initiated at the moment of the score’s coming into being. The parallel here is to what Robert Motherwell termed “plastic automatism”—a method in which a painting or other work of visual art is begun with an automatic gesture which is then elaborated on and completed through the intervention of techniques and formal judgments more or less consciously applied.)

If a way of reconciling the constraints of musical notation with the uncontrolled hand of automatism isn’t obvious, then how the associations of the deep imagination could be mapped onto music’s peculiar vocabulary and syntax is even less obvious. And that leads to the point—the point of referentiality–where the analogy between poetry and music comes apart.

Beginning with early works like Les Champs magnétiques and Poisson soluble, Surrealist automatic writing created its effects by disrupting the referential function of language, a function it takes for granted even as it opposes it. Its marvelous images and incongruities are such largely to the extent that they represent a displacement or disorganization of this function. It is from this overturning of the narrative and logical relations ordinarily conveyed by language that automatic writing derives its force. Surrealist automatism steered language away from the conveyance of meaning bound by logic or common sense and pushed it instead toward associative meanings rooted deep in the writer’s imagination. Surrealist automatism erased the ordinary semantic content of language, leaving a residue which included the auditory properties of language, or what Breton called the “tonal value of words.” But music is already tonal, both literally and in Breton’s more figurative sense, and it has no real capacity to refer to phenomena outside of itself. Lacking this properly semantic or description function, music wouldn’t seem to need or to be liable to the kind of signifying rupture Surrealist automatism was meant to bring about. In effect, music is already ruptured. To the extent that it could be said to have extra-formal meaning at all, music already is imaginatively associative.

The Belgian Interlude

Interestingly enough, given Breton’s official hostility—or at best indifference—toward music, there was at least one attempt at an explicitly Surrealist type of composition undertaken by a composer associated with Surrealism. The composer, André Souris, was a member of the Belgian Surrealist group. Although the Belgian group was allied to Breton’s Paris group, it was independent of the Paris group and thus not subject to Breton’s dictates. Souris, who was trained in violin, composition and conducting at the Brussels conservatory and who had an interest in the contemporary music of Schoenberg and Stravinsky, joined the Belgian group in 1925 and contributed to a series of musical pamphlets in collaboration with Paul Hooreman, who also was affiliated with Belgian Surrealism. With Hooreman Souris composed Trois inventions pour orgue, a work for barrel organ, a mechanical instrument for street performers somewhat similar to a player piano. The Trois inventions was a pastiche of familiar airs taken from popular operettas whose melodies Hooreman and Souris inverted while leaving their rhythms intact. The effect was to scramble the relationships between the notes while maintaining the source material’s rhythmic profiles. The inverted melodies would disorient the listeners at the same time that the unmodified rhythms would tease them with hints of the recognizable; the resulting frustration was meant to produce a transformative shock. What made the Trois inventions a specifically Surrealist composition was the extent to which it sought to defamiliarize the familiar and make the banal disruptive—a strategy consistent with the Belgian group’s idea of surrealist method, which was to alienate the mundane from its ordinary context, thus turning it into something disconcerting and consequently capable of opening up a rift in experience that would reveal the surreality within the reality of the everyday, common world.

By One Measure the Most Surreal of Artforms

As Souris’ music might suggest, perhaps Breton’s hypothesizing of a fusion of poetry’s inner music and music itself wouldn’t necessarily have to be effected through the application of compositional methods analogous to verbal automatism—assuming that such could be devised. Instead, such compositional techniques as collage, disruptive juxtapositions of musical material, distortions of pre-existing or familiar musical sources, or writing focused on timbral or textural effects could offer ways for consciously-working composers to simulate the logic-defying play of the automatic unconscious. Music doesn’t have to be written with Surrealist-inspired techniques in order to produce the effects desired by Surrealism; music’s real route to the marvelous would seem to lie in its capacity to provoke associations no matter how it was written. Given its nature, the place to look for the inner poetry of music isn’t at the point of creation but rather at the point of reception. And here is an irony. In 1928’s Surrealism and Painting, Breton faulted musical expression—“the most profoundly confusing of all”–for its imprecision and lack of clarity, which he declared to be inferior to the expression afforded by the visual arts. He consequently dismissed music with a much-quoted malediction: “So may night continue to fall upon the orchestra, and may I, who am still seeking something from the world, be left to my silent contemplation, with eyes open or closed, in broad daylight.” But it would seem that this imprecision is exactly what makes music suited to the Surrealist project of the reconciliation of the empirical and the imaginative.

It is music’s inherent inability to refer with any degree of exactitude that makes it able to provoke associations in a way that more definitely indicative artforms cannot. It is in the nature of instrumental music to be allusive rather than indicative or descriptive—it can’t be used to express propositions or precisely describe things or concepts, for example, and this is its advantage. By lacking a specifically referential function, it doesn’t foreclose associative or interpretive possibilities but instead opens them up; it suggests in a way analogous to the way an abstract painting suggests. Critic Harold Rosenberg described abstract painting’s meaningfulness as inhering in the “emotional reference evoked by color, by shape, by movement;” a similar observation can be made about music, substituting terms like “timbre,” “pitch,” “phrasing,” and “harmony” for Rosenberg’s color, shape and movement. By its very nature, music can hint rather than assert, and Breton’s claim in “Silence Is Golden” that music is “independent of the social and moral obligations that limit spoken and written language” would seem to be a concession, if an oblique one, of the liberating effect of music’s imprecision of reference. (And it carries a provocative echo of his approving description, in the first Manifesto, of automatism as being “exempt from any aesthetic or moral concern.”) In its evocative, non-descriptive use of plastic relationships based on sound, music would work in much the same way as the abstract painting, itself influenced by Surrealism, which was beginning to take shape among American painters right around the time “Silence Is Golden” was written.

That Breton understood the ability of sound to unlock creative associations in the listener is clear from his remarks in his “The Automatic Message.” There, he declared that what he called “verbo-auditive automatism” could provoke “the most exalting visual images,” images he thought would surpass the images elicited by “verbo-visual” automatism. Clearly, Breton grasped that the sounds of poetry could stimulate an upwelling of images in the reader/listener. (As for the content of the associations precipitated from verbo-auditive automatism…Whether or not they reveal hidden drives and other buried psychological material, or something less dramatic—unreflected-on structures of meaning or elements of temperament, or unsuspected relationships between things half remembered or idly speculated on—is a question best left to others.) By extrapolation—and not one that has very far to go—it’s easy to see how music can do the same just as effectively. Music’s affinity for the associative imagination may even make it the most surreal of artforms. If one wants to think of it that way.

Surrealism’s Musical Afterlife

It isn’t surprising, then, that while Breton and other orthodox Surrealists may have rejected music, music did not reject Surrealism. Of composers roughly contemporaneous with Surrealism’s first flowering during the interwar period, Edgard Varèse wrote Arcana of 1925-1927 having been inspired by dream material, while George Antheil, an American avant-gardist associated with Dada, wrote La femme: 100 têtes, a set of piano preludes inspired by Max Ernst’s Surrealist collage of that name. Antheil claimed to have been the exception to the Surrealist rule of no music; perhaps for this reason the poet Louis Aragon in 1930 proposed a collaboration in which he and Breton would supply the libretto to an opera whose music was to be written by Antheil. Unsurprisingly, nothing came of it. But since that time, Surrealist poems have been set to music and Surrealist poetry, painting and ideas have inspired instrumental music. Souris continued to compose from a Surrealist aesthetic, even after having been excommunicated from the Belgian Surrealist group in 1936 for having participated in a professional concert in a Dominican church; he would go on to become an important early influence on Pierre Boulez, some of whose own work was inspired by Surrealist poetry. (One could trace a line of descent connecting Surrealism to serialism.) For Surrealism, silence turned out not to be golden but rather something more akin to pyrite; instead, the gold of time that Breton claimed to seek is as likely to be found through sound as through any other medium. In spite of itself, the movement he founded almost a century ago continues to inspire music even now.

Works Cited:

André Breton, “The Automatic Message,” in What Is Surrealism? Selected Writings, edited and introduced by Franklin Rosemont (NY: Pathfinder, 1978).

___, “Is Silence Golden?” in What Is Surrealism? Selected Writings, edited and introduced by Franklin Rosemont (NY: Pathfinder, 1978).

___, Manifestoes of Surrealism, tr. Richard Seaver and Helen R. Lane (Ann Arbor: U Michigan Press, 1972).

___, Surrealism and Painting, tr. Simon Watson Taylor (New York: Harper & Row/Icon, 1972).

De Chirico, Giorgio, “Point de musique,” in L’Art métaphysique, ed, Giovanni Lista (Paris: L’Echoppe, 1994).

◊

Daniel Barbiero is an improvising double bassist who composes graphic scores and writes on music, art and related subjects. He is a regular contributor to Avant Music News and Perfect Sound Forever. His latest releases include Fifteen Miniatures for Prepared Double Bass, Non-places & Wooden Mirrors with Cristiano Bocci and In/Completion a collection of verbal and graphic scores by composers from North America, Europe and Japan, realized for solo double bass and prepared double bass.

More by Daniel Barbiero on Arteidolia →