Interview with Vishnupriya Rajgarhia

Colette Copeland

June 2024

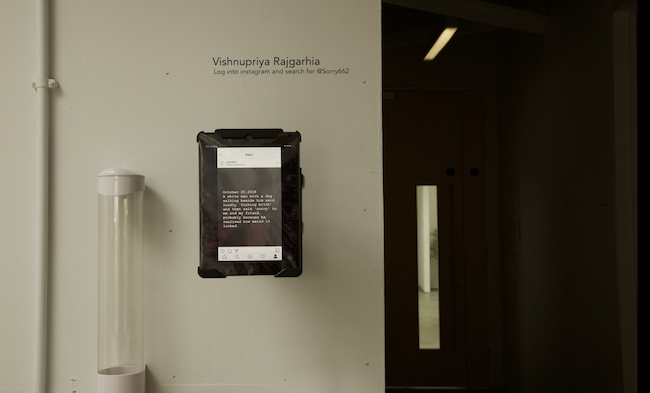

Sorry, installation view, photo courtesy of the artist

Sorry, installation view, photo courtesy of the artist

I met Vishnupriya in an online class through The Alternative Art School. Our workshop with esteemed artists of RAQS Media Collective focused on art and social practice—how as artists we might create “gatherings” outside of the traditional confines of the art world, as well as projects that challenge the boundaries between art, life and community. Vishnupriya shared some of her work with the class and I immediately connected with her subversive humor and focus on engagement with community.

Colette Copeland: In our RAQS Media Collective class discussions, you mentioned a few times your reluctance to call yourself an artist, citing it as a “heavy mantle” to bear. What do you mean by this? From my perspective, you have achieved a lot of acclaim as a young artist.

Vishnupriya Rajgarhia: Colette, I find this question very difficult to answer. When I started my rather unconventional journey into the arts, I wanted nothing more than to be an artist. I was always known for my creative streak, and to everyone around me it was the most natural progression–to pursue art professionally. Yet, when I started engaging with the thought of ‘impact’, and what art can and cannot do, I started leaning towards a post-studio practice without really knowing it. The idea of an ‘artist’ had changed in my mind, and I felt uncomfortable calling myself one, because I felt the way the world viewed an artist was very rigid. And yet, there were artists whom I deeply admired who had nurtured their commitment for decades and left a mark in society. Where did I fall in this spectrum? And so, I found it much easier to relate to the term ‘thinker’; it was an allied word, and it didn’t feel awkward when I pursued parallel interests like teaching at universities or consulting for international projects. The word thinker fit like an easy-going pair of pants that went with multiple occasions from morning to evening, and yet felt comfortable.

I am very grateful for the acclaim and recognition life has brought my way, and while I continue to make the work I do, I just do so without really announcing myself as a (conventional) artist, instead, I do it as a ‘thinker’.

CC: Thinker—reminds me of the wonderful Rodin sculpture and also the French flaneur—a person who sees the world through a kaleidoscope, whose role was to experience and “think” about life. Our current society does not have a place for flaneurs. I agree that the artist is seen as a rigid and marginalized profession.

While in graduate school in Oxford, U.K., you shared your experiences feeling like an outsider, even experiencing overt racism. Your online Instagram project responds to your experiences, addressing issues of racism and the language of “sorry” as a form of microaggression. Please discuss your decision to use the public space of Instagram, as well as the public’s response to the project.

VR: While at Oxford (an opportunity I remain grateful for) I was one of the many people who felt like an imposter. To see the density of brilliance one constantly surrounded by, was surreal. However, I did find it hard to find people who looked looked like me, and up until my arrival, I was never really aware of my brown skin. It’s only when I reached Oxford did realize, we were very different, and this realization deepened with callous remarks made by both students and faculty.

As an artist, I was early in my practice and career, and was determined that my work should engage with the public. I started questioning the idea of the public domain and wondered whether the internet, which we browse and consume so regularly could be considered a public space. This led to the decision to use Instagram as a tool for my project, Sorry.

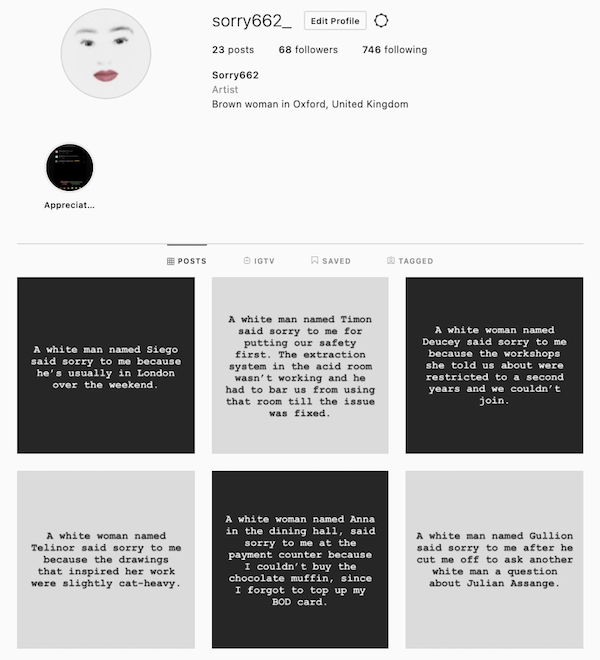

Sorry was not seen as a microagression by me, instead, I found it curious that I heard this word many times every day, followed by insensitive remarks. I decided to document and collect each ‘sorry’ I heard. As an Indian, we say this word very sparsely. It is only said when it is deeply felt–to apologize is to admit one’s error, which signals the ability to reflect on one’s actions. But I realized how banal the usage of sorry was in my environment, where people used it as a transition word. I simply wanted to share my observations with humor and see how the public responded. The response was thrilling to see; people appreciated the humor.

I started posting on Instagram under the handle Sorry662 and I realized that the goal I had in mind while treating both the internet as a public space and starting a conversation around a word that had lost meaning, and much needed to regain it, had resonated with people. It was a humorous way of engaging with a topic that required more conversation and awareness.

Sorry, detail view, photo courtesy of the artist

Sorry, detail view, photo courtesy of the artist

CC: Your use of humor proved to be an effective catalyst for engaging in dialogue.

The FreeTrade Museums installation is a very ambitious project, which spanned engagement with people from 5 countries. You sent instructions to communities to set up temporary structures as a place to gather and share experiences, then virtual conversations happening simultaneously around the world. I’m interested in this as an alternative model for institutions to reach new audiences and open up the idea of what constitutes community and social practice. Please share your insights on this project.

VR: FTM was a project born out of love. I firmly believe that love is the most powerful force in the world. In the backdrop of the 2018 surgical strikes between India and Pakistan, I wondered how one might tackle hate that was otherwise widespread. The decision to create a peripatetic museum, requesting participants to show us a part of their city or home that was important to them was a way for me to talk about culture within particular contexts.

I was thoroughly dissatisfied with conventional museum establishments and spent a considerable amount of time to devise an alternative space. (This occurred pre-covid, before digital spaces became mainstream). This element of institutional critique became very important to my practice over time. A digital museum that is virtual and connects people over intangible heritage was unheard of at the time and it was challenging to convince people of its viability.

In spite of the opposition to the project, including factors of impracticality and logistical concerns, I am glad I saw the project to completion. It was crucial to my research into interactive art, how institutions need to embrace innovation, and most importantly, how art can help build bridges of understanding between countries even when the world is hoping for war.

It was very interesting for me to explore materiality, as a necessity and a marker of an intervention. We used the inexpensive and disposable material cardboard and a digital device, to keep the museum as ‘object free’ as possible, almost antithetical to what one expects to see in a museum. We connected over 1500 citizens from 5 conflict states, and I’d like to believe this project helped us all understand the power of art, and the power of heart.

I was in a surreal state of shock when I heard that my research around this project had earned me a spot as a Research Fellow to represent the British council at the 58th Venice Biennale!

FreeTrade Museums, installation view, photo courtesy of the artist

FreeTrade Museums, installation view, photo courtesy of the artist

CC: Congratulations on your prestigious research fellowship at the biennale. What an incredible opportunity to continue and share your research and practice.

As you know, my Fulbright Research centers around themes of borders and boundaries. In the Sorry project, I see you pushing back against polite society, challenging the notion that an apology might excuse racism and hatred. In the FreeTrade Museums project, you expand the notion of what constitutes a museum experience, inviting people from other countries to participate in dialogues, as well as asserting that an art experience is not confined to four white walls. Please elaborate on how you explore these themes in your work.

VR: A professor once told me ‘one cannot go looking for a cause, it must find you.’ I never went searching for these themes or questions. These repeated experiences forced me to think about identity, institutions, borders, boundaries, race, belonging, context and culture very differently. Once I realized that I was thinking about these themes rather often, I found a way of articulating a response to them. It was a dialogue that developed over time, and that is how most of my projects have come about. Over the years I have surrendered to the fact that the ‘artistic process’, as scientific as it may be for me, is equally serendipitous.

My other projects, Body (is) an archive, Performance as Resistance, and explorations with text, also engage with these themes, but the prompt for each began with a different experience. This is perhaps one of the crucial reasons as to my I work outside a ‘studio’. Life happens outside and so my work must create a ripple where life blossoms.

Vishnupriya Rajgarhia’s website →

As part of her Fulbright Research Award in India, Colette Copeland has been doing a series of interviews with socially engaged artists whose work explores themes of borders and boundaries.

Interview with Hiten Noonwal →

Interview with Parvathi Nayar →

Interview with Manmeet Devgun →

Interview with Moutushi Chakraborty →

Interview with Riti Sengupta →

Interview with Jyotsna Siddharth →

Interview with Mallika Das Sutar →

Colette Copeland is an interdisciplinary visual artist, arts educator, social activist and cultural critic/writer whose work examines issues surrounding gender, death and contemporary culture. Sourcing personal narratives and popular media, she utilizes video, photography, performance and sculptural installation to question societal roles and the pervasive influence of media, and technology on our communal enculturation.