Interview with Shruti Ghosh

Colette Copeland

May 2024

from Droho/Drohita, a work in progress

from Droho/Drohita, a work in progress

I met Shruti while in Kolkata for my Fulbright Research when a mutual friend introduced us. She is a classically trained Kathak dancer, scholar and teacher. She participated in my India experimental soundings project, which focuses on amplifying voices that have historically been silenced, specifically female and queer voices. In her sounding rendition, she uses Kathak vocalizing to create rhythmic power and to voice out against oppression, which is a key theme in her artistic and research practice.

Colette Copeland: One aspect of Kathak dance that interests me is how the voice is used in combination with the body, as well as the ankle bells to create musical and rhythmic patterns as you move. Please share your background and training in Kathak dance and how you incorporate this and other movement forms in your practice.

Shruti Ghosh: I started training in Kathak dance when I was 5 years old. My father, Dr. Somen Ghosh is a tabla player and film critic/historian who introduced me to the world of music and cinema. I used to sit on his lap while he would be conducting tabla classes. So, I picked up some of the bols (mnemonic syllables) of Kathak dance, at a very early age, even before I could speak properly. When I started training under Guru Sumitra Mitra in Kolkata, I observed more closely, the importance of sound production in Kathak which mainly happens through tatkaar (footwork) and parant (recitation). Clapping is another aspect which is used during recitation of bols as the dancer demonstrates the rhythm and beat. The Qawwali and Sufi tradition of music which have lent a deep influence on Kathak also uses clapping as a movement during singing, as a sound and as a rhythm keeping tool. I have incorporated all these aspects in my work.

When I started developing short solo pieces at different points of time in my life, I used these bols as dialogues, as a means to express emotions or affects. In some cases, instead of using Bangla, English, Hindi, or any such ‘languages’ I used recitation of Kathak bols, to narrate a story, portray characters, create rhythm and to express emotions. This allowed for a re-contextualization of them into different socio-cultural contexts.

I have worked with dance practitioners and musicians (from different genres) as well as theatre artists both in India and abroad. Since I have keen interest in theatre and different movement practices, I try to apply what I have learnt from my experience of working with these artists coming from different socio-cultural backgrounds and practices. Kathak forms the basis of what I create but according to the particular theme/story/piece I am working on…I incorporate different kinds of movements which I think would help me most in expressing and communicating my story/message. Of course, I must mention film as well. As a student of Film Studies (masters), film has influenced the way I see, conceive and perform movement(s).

CC: Kathak dance has a rich Hindu and Persian history of storytelling. How have you adapted the tradition to tell contemporary stories about social injustice? I’m thinking specifically of your short film Droho that protests and memorializes the 1134 people who were killed in a garment factory in 2013 in Dhaka, Bangladesh.

SG: Thank you so much for this question. With the current socio-political climate where India is facing a right-wing fascist regime, it is of utmost importance to remember and constantly reflect upon the diversity and eclecticism that lie at the core of each and every aspect of Indian life. Kathak is a fruit of Indo-Islamic culture. I do perform dance on Urdu and Persian poems and songs as well as Bhakti poetry. These poems and songs speak of communal harmony, breaking caste barriers, fostering gender equality – the burning issues which continue to weaken the Indian society today. Both Urdu/Persian literature as well as Bhakti movement have contributed immensely to Kathak dance. I have done these short performances in different rallies, protest gatherings as well as cultural programs.

I have tried to recontextualize the story telling aspect of Kathak which defines the form – ‘jo katha kahe so kathak’ (One who tells a story is a kathak). In several Indian literatures, ‘Kathak’ refers to the narrator. I have moved away from the mythological stories which form the traditional repertoire to focus on issues and themes which help me narrate my contemporary times. While I do incorporate abhinaya (acting) and nritta (pure dance, i.e., footwork, hand gestures, pirouettes, of Kathak) in my pieces, I use them to tell stories of marginalized communities – their dreams, aspirations, struggles and resistances. It is my way of expressing my dissent about various issues and solidarity with these communities through my performance practice.

Droho/Drohita is a work in progress. দ্রোহ/Droho (meaning defiance/dissent) is a film created during the pandemic in mourning, in solidarity, in protest for the dismal working conditions of factory workers in Bangladesh and West Bengal, India. The Covid-19 pandemic made the situation worse with numerous factories closing down creating acute unemployment and workers facing daily lay-offs. The film acknowledges and commemorates the daily struggles and the sacrifices of the factory workers on both sides of Bengal. Building upon and extending the work of Droho, a live performance piece, দ্রোহিতা/Drohita was created and presented at Warwick University, UK (international conference on Locations of (Dis) Embodied Labour in Theatre and Performance) in November 2023 at Queen Mary University, London in March 2024 as part of a week-long workshop on Performance Labour and Automation.

In this piece, I use tatkaar (the footwork in Kathak) to show the feet movements of the women workers as they sit and work at the sewing machines for long hours. I use traditional Kathak hand movements and blend them with quotidian movements—ironing clothes, labelling apparels, washing clothes etc. to depict factory space and the worker’s routine.

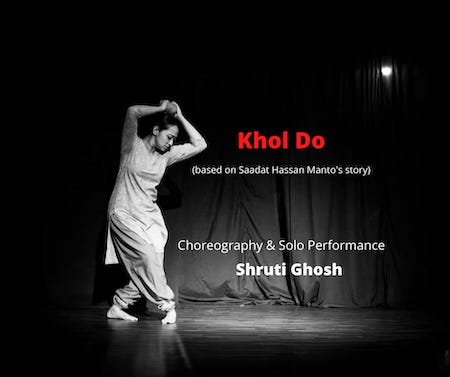

CC: In a recent article To Give Body To What Cannot Be Said by Chandrima S Bhattacharya published in The Telegraph, I read that you have written a one-woman performance inspired by author Saadat Hasan Manto’s short story Khol Do about a father and daughter attempting to cross the border during partition. The daughter goes missing and experiences unspeakable sexual trauma that is not overtly explained in the story. This work speaks to the prevalent sexual violence that so many women from various backgrounds experience in India. You have performed this work 28 times since 2022 in a variety of locations. How does this work incorporate art, activism and social practice? How did people respond to the work?

SG: 2022 was the 75th year of independence of India which meant that it was also the 75th year of partition of the subcontinent. The partition was a horrific event which engendered unspeakable violence and trauma. I felt the need to commemorate partition and actively remember it amidst the jubilant celebration of independence. This work was also inspired by the unabashed display of misogyny, patriarchy and violence perpetrated on women in different parts of India. How could I overlook those ‘disturbing’ news which fill my social media feed every day?

Khol do’s central plot as you mention is rape/sexual violence. As I performed it in different parts of India, both in the cities and villages, I found people not only related with it, but some women in the audience commented at the end of the performance – This is our story! The power of Manto’s writing is such that a story written 77 years ago still finds its relevance. As a performer, it is definitely heart-warming to find people relate with your work and respond to it but as an individual it breaks my heart that such stories are still relevant in the ‘digital’ India! It is shameful and scary.

As a Kathak practitioner, it was a challenging experience to translate Manto’s dark humor and theme of sexual violence through my movements. How can I do justice to his brilliant writing? How I can speak of something unspeakable…i.e., the trauma? These were the questions I was asking while choreographing it. Also, when I was choreographing the piece, it was very clear to me that I wanted to perform it in different kinds of spaces and for different communities/demographics. Once I decided not to remain confined within art practice spaces/places, it gave me more clarity about the choreography. I use very minimal (Hindi) dialogues taken from the story so that the basic story line can be conveyed. I use Kathak elements like footwork, pirouettes and counting of beats in a manner that these elements help convey the story and do not overpower the main theme. I am not here to attract/please the audience with complex movements/rhythm structures of Kathak. I don’t want it to be a display of skills. I want to engage the audience so that we can break the silence and begin a conversation. I will mention here a couple of responses which hopefully will give you an idea of the reception of the work.

A student from Ashoka University, NCR, Sonipat, said she found it very powerful and then as she spoke her eyes got teary. She added with much effort that she had seen/heard her grandmother waking up in the middle of the night and crying. As a child she did not understand much but as she grew up, she got to know that her grandmother had witnessed the partition – probably she herself faced multiple rapes or had known someone else closely who was raped. Her grandmother spoke of her childhood and life after her marriage and kids were born…the period in between remained absent…she never spoke about it.

In a rural area in Baidyabati in Bengal, I performed it on the street for a program in remembrance of the destruction of Babri Masjid and the aftermath that followed. The women in the neighborhood hardly spoke to me. They did not even sit on the mat which was laid for the audience. But they watched it from their windows or sitting away in their corridors, or standing at the gates of their houses. After the show, they gave 10/20 rupee note to their children asking them to contribute it as I was doing hat collection. They expressed solidarity through their silent gestures.

CC: Congratulations on your India Foundation for the Arts project. Please explain your research project and how this relates to the other areas of your practice.

SG: I am extremely thankful to India Foundation for the Arts, Bangalore (IFA) for choosing my project for Arts Research Program. This is short-term research (18 months) which I began last year in March.

This research investigates the cultural memory of exile and identity in a space called Chhota Lucknow situated in Metiaburuz, Garden Reach area of Kolkata. Nawab Wajid Ali Shah was exiled in Metiaburuz from 1856 till his death in 1887. His Kingdom of Oudh was annexed by the British. This is a crucial juncture in the colonial history of India as the following year witnessed the Sepoy Mutiny (1857) and then happened the transfer of power from the English East India Company to the British Crown.

A community of artisans, musicians, dancers and chefs migrated with the nawab to Kolkata. They recreated their lost home in Metiaburuz through architectures built by the nawab, tailoring shops specializing in Chikankari (embroidery) work and Lucknow style attires, specific rendition of thumri and ghazal along with amelioration of Kathak in Calcutta, and a cuisine which gave Calcutta its unique Biriyani. I consider Chhota Lucknow as a physical and symbolic space that embodies the narratives of displacement and exile. It was relegated into an unknown corner of the criminal underbelly of the Calcutta docks in post-colonial times, and in the present age of neoliberal capital it has been reduced to a ‘Muslim ghetto’ which in popular consensus is notorious for crimes.

This research addresses the narratives of displacement and identity formations of a demography undergoing systematic marginalization over several decades, from a community originating as descendants and custodians of Nawabi culture in Calcutta to a Muslim ghetto on the fringes of Kolkata waterfront at present, grasping onto a cultural memory of Lucknow and Wajid Ali Shah that is fast fading into oblivion. I undertake this research as a Kathak practitioner, teacher and an independent researcher who has written extensively on dance and its relationship with cinema and other creative arts. Therefore, I have identified the innovations in Kathak and associated vibrant culture facilitated through the settlement of this migrant community as a point of departure to start this research.

My first visit to Metiaburuz happened only a few years ago. I heard the name only in passing reference and had no idea about the place and people even though I was born and brought up in Kolkata and my entire Kathak training took place in this city! As a Kathak practitioner based in Kolkata, if I have to understand contemporary history of Kathak, how can I not know about Metiaburuz? How do I define and address Nawabi legacy? How do I understand the present day Kathak in Kolkata without knowing it’s complex trajectories across the city over the decades? This particular knowing would only come through a deep engagement with the place/space and the people who reside there. I am glad that this research has facilitated that ‘intervention’.

Also, in the face of continuous distortion of historical facts, destruction of historical sites and documents and erasure of history, I hope to weave through my research a ‘story’ that comes from the common (marginalized) people of my city and from the forgotten lanes of neglected areas which would hopefully address the ‘absences’, ‘lapses’ and ‘forgotten memories’ and thereby contribute in redefining and rewriting Kathak history in Kolkata.

As part of her Fulbright Research Award in India, Colette Copeland has been doing a series of interviews with socially engaged artists whose work explores themes of borders and boundaries.

Interview with Hiten Noonwal →

Interview with Parvathi Nayar →

Interview with Manmeet Devgun →

Interview with Moutushi Chakraborty →

Interview with Riti Sengupta →

Interview with Jyotsna Siddharth →

Interview with Mallika Das Sutar →

Colette Copeland is an interdisciplinary visual artist, arts educator, social activist and cultural critic/writer whose work examines issues surrounding gender, death and contemporary culture. Sourcing personal narratives and popular media, she utilizes video, photography, performance and sculptural installation to question societal roles and the pervasive influence of media, and technology on our communal enculturation.