Interview with Riti Sengupta

Colette Copeland

November 2023

Photograph from Riti Sengupta’s series things I can’t say out loud

Photograph from Riti Sengupta’s series things I can’t say out loud

I recently met photographer and artist Riti Sengupta while in Kolkata. She is a graduate of the Masters of Design in Photography program at National Institute of Design where I was recently in residence as a guest faculty member. Her work explores issues of gender, domesticity, identity, and memory. Feeling isolated during the pandemic, Sengupta founded the photo collective Eight Thirty, comprising nine female photographers from across India.

Colette Copeland: We spoke about the origins of your project Things I Can’t Say Out Loud, that began during the pandemic when you returned home, living with your parents after eight-years apart. Confronted with dominant patriarchal structures within the family and the unfair pressures placed upon your mother, as well as her complicity, the work first began as a series of “kitchen conversations.” These conversations then led to a series of photographs. Tanvi Mishra insightfully described the work as “an intergenerational dialogue between the artist and her mother, through which they excavate their identities as women within the family home.” In thinking about the term excavate as it relates to relationships and memories, I imagine there were many difficult conversations. Once you decided to use photography as a tool to explore these exchanges, how did you determine how to distill an entire conversation into a single photograph?

Riti Sengupta: There were several difficult conversations for sure! I don’t think I would be able to sum up all these conversations and experiences in a single photograph, which is why I decided to work with a series of images. Domesticity and womanhood are multi-faceted and complex, so I thought a single photograph may not be able to do justice to all of it. I made audio recordings and written notes of the conversations with my mother. When I listened to the recordings or referred to my notes, parts of the conversation resonated with me. I found certain aspects which I wanted to share with others. These moments inspired the photographs.

CC: This series represents a departure from your previous documentary work. The staged photographs are performative, with your family members enacting metaphoric and symbolic gestures for the camera. The stark photographs speak to the invisibility of labor and constraining domestic roles, but also hint at absurdity, which emphasizes the unrealistic expectations set upon women. It’s difficult for me to narrow down my favorite images, but I keep coming back to the red tape over the eye, the stacked pillows on your mother’s lap, and the two images of your brother—one with red yarn on his face and the other with your mother and the cotton cloud. Please expand on the symbolism and performative gestures in these powerful works.

RS: Many of the objects used in these photographs are common everyday things which we see in most households. The idea behind using these objects of domesticity came from associations that we make with them conventionally, culturally and at times colloquially. For me, the challenge was also to elevate them, to somehow charge them with meaning. The repeated use of red suggests its association with femininity and marriage, but also with violence. The tape implies the act of shutting down, and sealing, and hence censorship. The red yarn hints at blood ties and the complexity of them. With the photograph of the pillows on her lap, which of course signifies the burden of domestic life and the repetitive monotony of it, there is also an element of irony in it because usually one would imagine a pillow as something light and comforting. I have consciously tried to use certain metaphors and symbols in these photographs, yes, but I also think many of them are ambiguous, which allows them to be read in different ways. What is interesting to me is how others perceive these photographs and what meaning the symbols or performances hold for them.

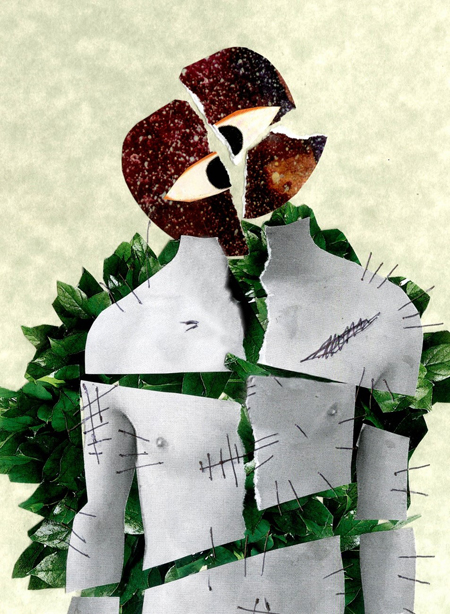

Photograph from Riti Sengupta’s project AIN

Photograph from Riti Sengupta’s project AIN

CC: Let’s discuss one of your earlier projects, AIN from 2016. Inspired by the short story Bolai written by Rabindranath Tagore in 1928, the collaged works explore themes of the desire to belong, and the inability to expressed one’s own identity freely. This imaginary character AIN lives in a parallel dream world. The collaged text, illustration, and imagery, as well as exploring one’s dreams is rooted in surrealism. How has surrealism influenced your work?

RS: I think I’ve always been fascinated by children’s novels and the illustrations you come across in them because they offer another world where you can lose yourself. My interest in surrealism perhaps also comes from my curiosity about alternate realities. Looking back, the visual language in AIN reflects the fact that Bolai was a childhood story that I grew up with.

CC: Responding to the storyline, does AIN ever find the secrets to the universe? The ending was quite sad. It speaks to longing and the erasing of oneself. The last line — “With every tear drop, a little bit of her faded away.” Have you envisioned another narrative series with AIN and/or using collage as a tool for storytelling?

RS: I don’t know if AIN ever finds the secrets to the universe. In the end, he escapes to the vast unknown. This escape to me signifies freedom. Yes, the ending is quite sad but, in a way, I feel relieved because he is freed from an identity that is imposed on him. I haven’t really thought about another narrative series with AIN, but it’s interesting how this idea makes me ask myself what happens to AIN next.

CC: My research focuses on the themes of borders and boundaries–physical, emotional, real, imagined, geographic, convergent, and divergent. How does your work fit within these themes?

RS: The idea of boundaries is not something that I’ve consciously thought of as a thematic representation in my work. In reflecting upon that further, I wonder at the complex interplay between boundaries and identities, and how boundaries play a role in shaping our sense of self. Gender has traditionally been used to establish boundaries that dictate roles, expectations, and privileges within society. I’m also beginning to think about how boundaries can become more fluid or be redefined to go beyond these gender constructs.

CC: The idea that boundaries can be challenged and redefined is present in many of your photographs. You create visual boundaries that obscure the identities of your characters, thus challenging gender roles and constructs. Things I Can’t Say Out Loud is an ongoing project. How do you envision its evolution from here, especially given that your family is tired of performing for your camera?

RS: I think I’ve been quite demanding of my family these past couple of years and my mother especially has always been generous in her participation in this project. My family looked at this like a play or a game, but over time, it is something that they have become bored with. So, I’ve been thinking of ways to reinvent the process. I have started turning the camera more towards myself, alongside documenting spaces and still life. I’m also considering adding new characters in the story, but I am not fully resolved about how to weave them into the narrative yet.

Photograph from Riti Sengupta’s project AIN

Photograph from Riti Sengupta’s project AIN

Riti Sengupta website →

Follow Riti on Instagram →

This is the fifth in a series of interviews Colette Copeland will be doing as part of her Fulbright Research Award to India. Her research focuses on socially engaged artists whose work explores themes of borders and boundaries

Interview with Jyotsna Siddharth →

Interview with Mallika Das Sutar →

◊

Colette Copeland is an interdisciplinary visual artist, arts educator, social activist and cultural critic/writer whose work examines issues surrounding gender, death and contemporary culture. Sourcing personal narratives and popular media, she utilizes video, photography, performance and sculptural installation to question societal roles and the pervasive influence of media, and technology on our communal enculturation.