Interview with Avnit Singh

Colette Copeland

April 2024

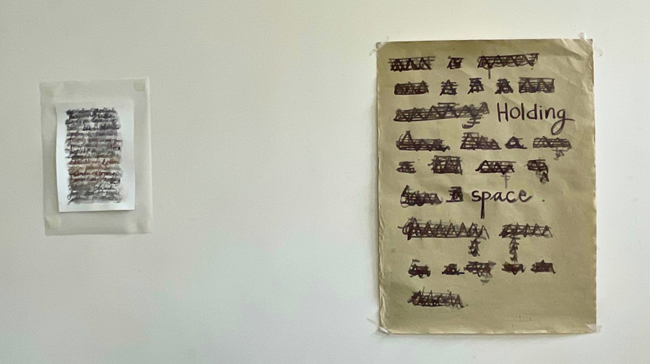

from Holding Space, asemic and redacted text, SSVAD residency, 2024

from Holding Space, asemic and redacted text, SSVAD residency, 2024

I met Avnit in Shantiniketan, a wonderful artist enclave in West Bengal. The town’s name which means the “abode of peace” was founded in 1863 by Debendranath Tagore. His son, esteemed poet, philosopher and philanthropist Rabindranath Tagore who won the Nobel Peace Prize in Literature in 1913, founded the university Visva Bharati, which is well known for its arts and other programs. It is now recognized as a World Unesco Heritage Site. I was invited to speak at the university to the printmaking students, as well as give a lecture at the arts and culture institution Arthshila on my experimental sound project—amplifying female and queer voices in India. Avnit attended my talk and we had a breakfast discussion the next day about her work. She is based in Bangalore and just completed a residency at SSVAD in Shantiniketan.

Colette Copeland: When we were discussing your two projects—The Museum of Absence and 101 Ways To Be A Forest, I couldn’t help but think about the Fluxus art movement and how the artists reimagined possibilities in art, asking questions such as what constitutes art, challenging the idea of art as commodity, celebrating the dissolvement between art and life and art happening in collaboration with others. How have the Fluxus methodologies inspired these works and your practice in general?

Avnit Singh: Fluxus has definitely been an influence on my work, especially in terms of challenging traditional notions of art and embracing experimentation and collaboration. I attribute this interest to my mentor Leslie Johnson whose presence and guidance have influenced how I work. She was my professor at Srishti School of Art, Design and Technology in Bangalore. When she introduced us to Fluxus, it felt very close to my thoughts about art, resonating with me on a deep level.

For example, The Museum of Absence explores the idea of absence and memory through the absence of physical artifacts, questioning what constitutes a museum and what is worthy of preservation. This concept aligns with rejection of art as a commodity and its emphasis on art as a process rather than an object. Similarly, 101 Ways To Be A Forest incorporates elements of Fluxus’s happenings and scores, using absurdity and humor to address serious issues like environmental degradation. While I wouldn’t say my work is directly inspired by Fluxus, there are certainly parallels in my approach to artmaking and conceptualization. It fascinates me how art making is not separate from living. Art is constantly happening in the mind and the body.

CC: Community engagement and social practice are integral to the two projects we discussed. Please speak about your process and practice when collaborating with communities and how that shapes the outcome of your project. What opportunities arise for dialogue, not only with the participants, but also with viewers?

AS: I believe in human interactions and the power of relationships. I believe that my process of artmaking involves dialogues. The conversations and individual experiences come together to the realization of connectedness.

When I was young, I had a weekly ritual with my Chachu (paternal uncle). On Mondays, we would eat something sweet, usually a pineapple pastry. As I grew up, the ritual slowly disappeared. One day, I ate a pineapple sweet which reminded me of those memories. The places where we went were no longer there and only the memory remained.

In an effort to retain those fleeting memories, I asked all my family members to bring pineapple pastries to our gatherings. These gatherings resulted in storytelling. I asked my family to share their memories of what they hold close. These experiences influenced my research and community engagement process.

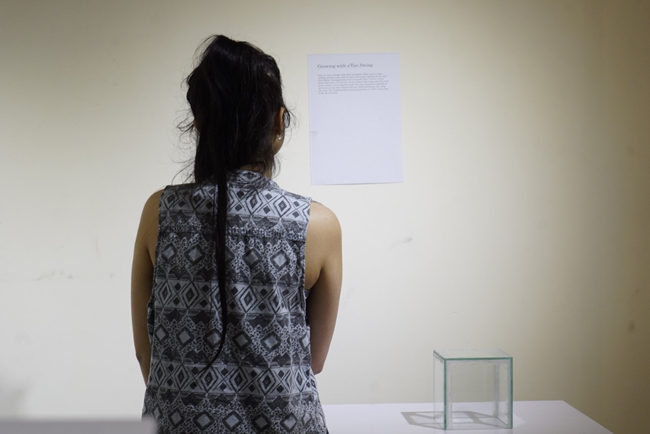

The idea of The Museum of Absence began when I lost my grandmother in 2014. A few days later on the way to work, my laptop, hard drive, camera and wallet were stolen from my bag. During the bus ride, I was thinking about loss, but taking comfort in the videos and photographs that keep loved ones’ memories alive. The perpetrators must have removed everything from the cloud as well since I couldn’t retrieve anything. The empty void inside me led to the idea of The Museum of Absence because I had nothing to show in terms of physical objects, but I had important, deep memories in my mind.

For the project, I asked people to share stories of loss and memories with me. The texts I received from people were displayed in the exhibition on the wall behind empty vitrines placed on pedestals. When viewers came to see the exhibition, they also shared their memories with me. In the installation, there was another room that was empty, but had audio playing people’s stories. The prevailing idea is that we are all museums or repositories of memories.

Another part of the installation held a room full of boxes and drawings. Inspired by the stories I received from people, I made drawings visualizing their memories. The room became a physical manifestation of the compartments of memories in our mind. The temperature in this room was cold and due to the precarious arrangement of the boxes, people could not enter to engage with the materials. This represents the loss of memory that occurs as time progresses.

The last room contained a small kitchen, where I sat and served tea. Many people came and sat with me. Some cried and told me that it was a cathartic experience for them. The collaborative components of the project are integral to my practice.

from The Museum of Absence, collaborative performance, 2018 – ongoing

from The Museum of Absence, collaborative performance, 2018 – ongoing

CC: As you know, my Fulbright research centers around themes of borders and boundaries—physical, emotional, real, imagined, geographic, convergent and divergent. I see your work pushing boundaries in terms of your process and ideas. How do you see your work through the lens of these themes?

AS: This reminds me of a funny story from a classroom project. Two classes were allotted one room, and we were supposed to share space. The other class wasn’t respectful of the idea of sharing and respecting boundaries. It was a course on installation as art, so we made a very chic entryway with velvet for our side of the room. We also created demarcations of boundaries with display boards and frames made from velvet and barbed wire. The velvet denoted a VIP border while the barbed wire references LoC (line of control—the acronym refers to a military control line that is not a recognized international boundary, but de facto boundary). It was quite a playful instal which came out of frustration.

In 101 Ways To Be A Forest, I examine the boundary between humanity and the natural world, highlighting our interconnectedness with the environment and the consequences of disregarding these boundaries. Through my art, I aim to stimulate reflection on the fluidity and permeability of borders, prompting viewers to reconsider their perceptions and assumptions.

It’s such an animal instinct to mark territories, as my cats remind me daily. I was denied a visa recently, and I think work will come out of this experience. I planned to visit my mentor in Sweden and the Swedish government denied my visa application because they made assumptions and accusations that I pose a threat for illegal immigration. The rejection letter was very detailed and derogatory. I feel frustrated and triggered. I just wanted to fly and visit someone that I really appreciate. We were supposed to collaborate together, and nothing could happen because of a bureaucrat’s misconceptions.

CC: You recently completed a residency at the Shantiniketan Society of Visual Art & Design (SSVD). How did this experience impact your work?

AS: During my SSVAD residency, I embarked on a journey to find my personal space, encompassing physical, emotional, and mental dimensions. Sharing a room with two other artists highlighted the constant performance demanded by communal living. Amidst this, I grappled with the recent loss of my uncle, a close confidant, rendering me hesitant to share my grief with others.

Struggling to reconcile the absence of solitude, I sought solace in small comforts, like a cup of tea, and the relationships I formed with fellow residents, particularly the women whose contributions often went unnoticed. To shed light on their overlooked roles, I created drawings using nearly invisible ink, symbolizing their silent presence.

My quest for personal space was further challenged by unexpected intrusions, such as discovering a CCTV camera outside our room. Despite these disruptions, I endeavored to carve out a space for collective mourning, hosting conversations that delved into our shared experiences of loss and grief.

Reflecting on this experience, I realized the importance of asserting oneself in communal settings while also respecting the boundaries of others. Although I initially hesitated to share these thoughts, fearing confrontation, I recognized the value of open dialogue in fostering understanding and empathy.

In the end, my time in Santiniketan became a journey of self-discovery, navigating the complexities of personal and communal space, and finding solace in shared experiences and meaningful connections.

During this time, I found solace in writing. It became my sanctuary, offering me the space I yearned for. Now, I’m eager to delve into text-based works, utilizing the power of words to express myself. Additionally, I’m seeking a suitable studio space. I long for a dedicated studio where I can immerse myself fully in my creative process. I trust you can understand and perhaps relate to this desire for a space of one’s own.

As part of her Fulbright Research Award in India, Colette Copeland has been doing a series of interviews with socially engaged artists whose work explores themes of borders and boundaries.

Interview with Hiten Noonwal →

Interview with Parvathi Nayar →

Interview with Manmeet Devgun →

Interview with Moutushi Chakraborty →

Interview with Riti Sengupta →

Interview with Jyotsna Siddharth →

Interview with Mallika Das Sutar →

Colette Copeland is an interdisciplinary visual artist, arts educator, social activist and cultural critic/writer whose work examines issues surrounding gender, death and contemporary culture. Sourcing personal narratives and popular media, she utilizes video, photography, performance and sculptural installation to question societal roles and the pervasive influence of media, and technology on our communal enculturation.