Interview

Joseph Thompson (MASS MoCA)

Christine Hughes

November 2014

CH MASS MoCA has been open for 15 years now?

JT This is year 15, but for me personally 13 was more significant because we had then been open longer that it took to get open to begin with.

CH Can you give those of us who have never been to MASS MoCA some background of the museum and how it got started?

JT “MASS MoCA One” exists, the idea of it, and it’s called DIA Beacon. DIA Beacon is a beautiful monument to mainly large scale, mainly minimal art of the 70s and 80s.

The original idea for MASS MoCA was that we were going to borrow works from Ileana Sonnabend and Charles Saatchi and Giuseppe Panza, works by Judd and Flavin and Morris and Serra, large works that required ample time and space, install them and leave them up for a very long time.

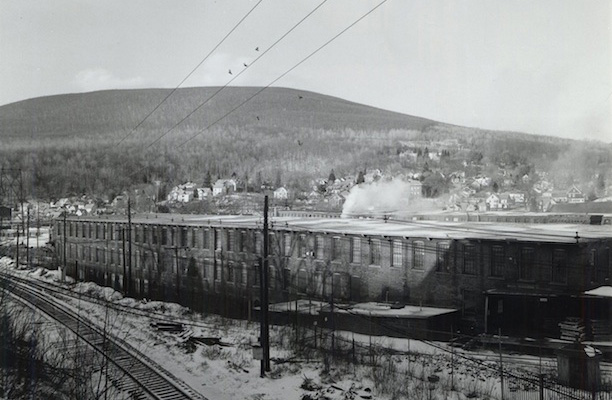

These buildings are gorgeous, a factory campus 26 buildings 600,000 sq. ft of floorspace, 16 acres, roughly a third of the downtown business district of North Adams. The former occupant, Sprague Electric, had closed in the mid 1980s when we first proposed this idea. It was simple: clean the buildings up and install these large bodies of work which were as much environmental as landscape in orientation.

CH So you were setting out to start a museum?

JT Absolutely. More of a fixed depot, a place where large monumental works came and were sighted for a very long length of time. It has relativity little to do with what MASS MoCA is today.

CH Kind of the opposite, isn’t it?

JT In fact it is.

In the early 90s, as we were trying to bring money, buildings, art, political support, philanthropic support all together at the same time we introduced several really important changes.

One is the idea of doing changing exhibitions. Secondly, we really turned ourselves with great enthusiasm to the performing arts. I have a friend Sam Miller who is running Jacob’s Pillow, a fabulous dance festival in Becket. He used to chide me saying “Joe, if you are serious about being a platform for all contemporary art you need to speak of the performing arts in the same breath as you speak of the visual arts.”

People from afar think of us as a place for visual art, but as you get closer and closer to us here regionally, people think just as quickly of MASS MoCA as a performing arts venue. We produce some 80 performing arts events every year. Some of them are quite elaborate, mainly music festivals that go on for 3 or 4 days. Some are elegant quick events; poetry readings and films. Performing arts is a big part of our financial, emotional and intellectual bandwidth.

It’s an interesting institution in that way.

CH Now, when you say “we” is that the Royal “We” or is that you and someone else?

JT Absolutely not. Projects like this don’t get launched by oneself, that’s for sure. The specific history was in the mid 80s. Sprague Electric Company was leaving camp. Over the 10 years leading up to that, 4,000 jobs had disappeared in a town of then 16,000. North Adams was facing a huge socio-economic crisis. It was as though a neutron bomb had gone off.

CH Are you from North Adams?

JT I’m from Williamstown, just down the road. Williams College. Tom Krens, then the Director of Williams College Museum of Art, (who went on to the Guggenheim), Michael Govan was there, (Michael went on to DIA then to Los Angles to LACMA) and I was there. Five of us came to North Adams because Tom had an idea. The idea was to take advantage of this surfeit of space. North Adams sits cheek by jowl with Williamstown, The Williamstown Theater Festival, The Clark Art Institute, The Williams College Museum of Art, Jacob’s Pillow and The Norman Rockwell Museum. Tanglewood is just down the road and attracts 400,000 people a year. If you add up the group of really fine cultural institutions within 30 miles of North Adams it’s an amazing constellation. Two and a half million people a year come to the Berkshires to enjoy the arts, take hikes and go skiing. It’s cultural tourism. None of them were going to North Adams. So the idea was, let’s take advantage of these buildings and go out and find art that would fit, that didn’t need fancy buildings, climate control or elaborate architectural detailing. Art that could live well in these raw, rough hewn, industrial buildings. In the hopes that people would add a trip to MASS MoCA on their Berkshire itinerary.

We pitched this idea to the state, who was looking for a ways to reconfigure North Adams. There were big problems here. Twenty-eight percent unemployment. North Adams was number one on every list you don’t want to be number one on: unemployment, teenage pregnancy, domestic violence, illiteracy. So it was a town in desperate need of a fundamental makeover and our pitch was a lot of things work well in Berkshire County and, at the heart of them, are creative industries, education, cultural institutions. If you could attach North Adams to that segment of the economy, life would probably be better. That was an argument that we began in 1986.

CH So, do you have government funding? I could never really understand how to tease that out?

JT Yes, we sought and ultimately won a 35 million dollar grant from the Commonwealth of Massachusetts for the initial makeover of the buildings. It was a long time coming. We thought we had the money in 1987. Governor Dukakis was our Archangel. He went off and ran for president, lost that bid and came back to a crumbling economy in the late 80s early 90s. It was rough sailing. The money never came. Tom and Michael went off to New York. I stayed here to become the first director of the institution.

I essentially spent 12 years trying to put Humpty Dumpty back together again in the aftermath of the collapse of the economy of Massachusetts. We had a change of governors. A Republican, Bill Weld, took office. At first he didn’t think so highly of the project. He was quite skeptical.

CH So you weren’t open at that point?

JT No, the buildings were abandoned, pigeon infested, water was coming in the roof, beginning slowly to fall apart from 1986 until the year we finally started construction in 1997. So, it took 10 full years raising money, working with artists and collectors, working with governors as they would come and go, trying to convince them that this project had logic and was not a crazy thing. The idea of putting a very large museum of contemporary art in North Adams is not the first thing that comes to mind when you’re thinking of economic redevelopment. We had a lot of explaining to do.

CH When you set out, did you decide that you were not going to have a permanent collection of any sort? You were just going to have revolving exhibitions?

JT Originally, it was going to be very long term loans. Very long term loans to a 26 year old, which is what I was back then — meant 7, 8, or 9 years. During that period when we were struggling with the particular burdens of this institution, I spent a lot of time on the road talking to people who love art from Chicago and Los Angles, Boston and New York. I was out rattling my tin cup looking for private support. One of the things Governor Weld wanted to see was whether this project could attract private philanthropic support because there was going to be no operating money coming from this. The state grant was strictly to build this project. As part of that effort I would go out and talk to hundreds of people and I heard this question over and over again “Are you sure people are going to come twice? Even if you install it perfectly and it is the best installation of American and European Minimal art of all time, are you sure people will come a second visit?”

That question began to haunt me.

CH Why a second visit? What would be the difference? Were you afraid after one visit they would check it off their list?

JT What was concerning to me were the people who were asking the question. These were people who loved contemporary art, the deepest most ardent supporters. It occurred to me if these great collectors and people who really care about this art are asking what’s going to motivate me to come back, we could have a problem on our hands because this was never going to be a well endowed operation. We needed members who supported it and activity to engage our community. So that question troubled me and I began thinking about the relationship between permanent installations and changing installations and between the performing arts and the visual arts.

The other thing I began to hear a lot and think at the time was that Beacon is an hour out of New York, you can take a train from Grand Central to DIA’s front door, it’s a beautiful institution that has an endowment perfectly able to function with however many visitors they get a year.

CH With or without visitors.

JT Yes, exactly that’s the point. Well put. I think that had we built “MASS MoCA One,” we probably would have gone out of business in the first 2 or 3 years.

CH So maybe it’s good that it took a while to get this project off the ground?

JT Not just maybe. I think in some ways that long gestation period and the chance to think deeply and retool the program and think about these issues were pivotal in the fact that we are still here. And our visitation has grown nicely. In the first year we opened we had 45,000, then 80,000 and for a long time we were at 100,00, and last year we topped 165,000 visitors.

CH Now you have more visitors than you have square feet.

JT Finally. That’s a good mark.

CH And you are going to start phase 3, which is going to give you another 130,000 more square feet?

JT Well, so, that brings us back full circle in a way. We developed a program of changing exhibitions of art and ran this 2 or 3 ring circus. We were always as good as the last show we did. We had done some really wonderful exhibitions.

In 2003 I was approached by Jacques Reynolds and Sol Lewitt. One afternoon they came for lunch with an idea, it turned out to be a big idea. Sol spent the day looking around buildings and over lunch he said, “If you give me building seven, I’ll give you a very beautiful exhibition.” I asked him which part of building seven? It’s a very big building. It’s 30,000 square feet. That is as large as the whole Whitney on Madison Avenue.

Sol just looked at me and said, “The building in it’s entirety.” Six months later he delivered a beautifully handmade model, a maquette, which contained the exhibition just as you see it today, or nearly so.

In a way that was a return to the original idea because this is a 25 year changing exhibition. It’s a very long term temporary show. That in turn lead to the second iteration of this idea, the collaboration with the Hall Art Foundation, who owned a great Anslem Kiefer collection. We now have 2 very long term quasi-permanent core collections. They are not our works, they belong to the lenders.

CH They are taking up your floor space.

JT They bring all the attributes of a permanent collection with none of the liabilities. Once you decide to collect as an institution, it leads you to a different way of thinking. You need registrars and conservators and you begin to think of your mission as conserving and protecting and presenting works. That’s not the mindset of MASS MoCA, we spend our time thinking about what’s coming. How we can work with artists who are living now to make work.

Most museums understand themselves as a box, we really like to think of ourselves as an open platform.

CH Who chooses the work? How many curators are there?

JT We have 2 curators who organize the changing exhibitions on the visual art side and 1 curator who does our preforming arts program.

CH And are you involved in curating? You seem very interested in art.

JT From time to time they let me stick my nose into it with absolute horror. I do an exhibition usually every year or two. I was deeply involved with Jacques and Sol and the Lewitt installation and recently did an interesting exhibition with Xu Bing, the Chinese artist. That piece is now in a temporary installation in St. John the Divine in NY. From time to time they will let me do exhibitions.

CH I was asking about the additional space. Is that a correct number 130,000 square feet? New buildings?

JT It is an existing building. All of MASS MoCA is in existing buildings. The Kiefer installation we did a little bit of fussing with. It’s one of the beautiful things about this factory campus. The buildings are rough, raw, vernacular architecture. One of the secrets of MASS MoCA is you can feel the presence of human labor in these buildings in large part because we haven’t hidden it. For 120 years, thousands of people worked here every single day, first making printed cotton, then making electronics.

That in itself is interesting, the metaphoric arc in these buildings. We’ve gone from literally material cloth which people wore on their backs and covered their furniture with, to electronic components, if you will, capacitors, produced here in the great age of radio and TV, which you could hold in your hand, but the value in them is really in the intellectual property, the research and development that gave rise to the electronics within them, to what we do now, which is pure art. People leave here with thoughts in their heads, smiles on their faces, emotional attachment.

You’ve traced the arc from industrialization to post industrialization from hardware to software from material to immateriality, which describes the arc of our society as a whole, of these buildings. I love the aspect of this factory campus.

CH I love the visceralness of the buildings.

JT They’re beautiful.

CH Yes they really are. They are all very different.

JT They’re human too. The panes of glass are as big as your head, the bricks are made to hold in your hand one by one.

CH The scale of the building is a lot different than the scale of the art in the buildings.

JT That’s very interesting. There’s also something that happens from inside to outside. You look at them from the outside and they seem like big red, hulking, dark mill buildings, Dickensian. Once you come inside they’re actually full of windows. MASS MoCA has more side light than any museum I know. There are windows everywhere. So it’s an incredible light filled experience as you walk through these buildings which from the outside look dark and foreboding.

CH That’s very true. How much does the size of the space of the galleries play into what you choose to show?

JT It’s key. I think the best works that we show are by artists who enjoy working in a new scale, almost a theatrical scale, often quite spectacular in scale. We enjoy working with artists whom we feel are ready to take their work in a new direction or are interested in crossing over from one field to the other.

CH Because a lot of work is site specific, right?

JT Much of the work is made here. It’s one of the things we are proudest of as an institution are our workshops. We have great art fabricators, Richard Criddle and Dante Birch. These guys can literally make anything from welding metal to complicated cabinet work to complex audio visuals.

CH Are they making the art for the artists?

JT Absolutely.

CH That’s a change that’s happening these days.

JT We do a ton of fabrication work. I think there are 100’s of major works of art that are out in the world now that have been born in our workshops or have been born on our stages through technical residencies. We do a whole series of residencies. David Neumann is here right now making a new work. Teresita Fernandez has been here for a couple of weeks making a whole new body of works that are especially sized and scaled for these particular spaces we are showing them in, and because our buildings are big, they tend to be large works.

CH So what happens? Do you ever place a work for an artist?

JT From time to time. It’s rare because they are demanding works, not works you typically hang on your wall or put on a pedestal. It does happen.

Cai Guo Qiang’s series, with fireworks coming out of them, are now installed permanently in the Seattle Art Museum. Those were made here and went on to have another life. There are dozens of works that collectors with silk scarves and goggles come along and snap up and find ways to show. It always astounds me that this work, which is clearly institutional in scale, can somehow find its way into private hands.

More often than not we make a work here and show it for a year and take it apart. We try to salvage and recycle the material. Sometimes we work with the artist to find second and third places for it to show. Tim Hawkinson’s really marvelous Uber Organ was made here in 2000, one of the first works made here. He did the whole thing with his own hands, and it went on to have a really lively life. It traveled to Mexico, Texas, New York City and found its way to multiple venues. We love it when works get made here. We recently teamed up with the Public Theater in NY and the Theater Festival. David Byrne and Alex Timbers made a really marvelous new work called Here Lies Love, which was made here over a 6 week residency and went to the Public and will probably end up traveling around the world. We like nothing better than having artists come, be here, live and work among our friends in North Adams and make work that goes out into the world.

CH Is this the only museum in the country that does something like this?

JT No, other museums do it from time to time, but it’s part of our DNA. We have a few things that make that easier. We are in the country. Things are more economical here than in New York or Boston. We have housing so artists can come and stay. Their technical assistants can come and stay. If we need engineers and specialists to come and stay, it doesn’t break a bank. We have this great tool set, which is the result of our crossing over between the performing and visual arts.

A lighting designer who works in theater knows in their pinky what a lighting designer who works in a museum knows in their whole body. It’s just a completely different level of sophistication. That applies for all kinds of staging. We’ve got this secret weapon, which is our performing arts production staff, who now how to do theater on a large scale. That’s very valuable for artists who are making works this scale and vice versa. When dance choreographers are here and looking for help on stage doing lighting or back lighting or creating video backdrops for their work, having our art fab crew do that for a living, you get all kind of multiplying factors which happen by not just having the spaces, which are important, but also the people who know how to make things.

CH Do your curators travel around the country looking for artists, or do artists come to you with proposals? How do you find what you will show?

JT Most of the time our artists are doing their own research, following their own noses, often after having conversations with artists who were here the previous year. The best question to ask an artist is what work they have seen recently that interests them. That often leads you to some really good new work. Darren Waterston had this marvelous piece, a kind of psychedelic riff on James McNeill Whistler’s Peacock Room, which he built using a one to one scale model of Whistler’s Peacock Room and then modified it rather dramatically.

CH That’s up right now?

JT Yes. Go see it, it’s a fantastic show. He is a super painter who had this fantasy of doing this work which we helped him realize. That was a cold call in a way. He proposed this work which went from a wall mural, to a painting exhibition to this very elaborate 3D installation.

CH Who is your audience typically? The last time we were here we saw a lot of parents with children.

JT It’s hugely diverse. This time of year we are really a local regional museum and most of the people you see this week are parents bringing their kids.

We shift dramatically in the summertime to a heavily New York metropolitan audience. Over the course of the year almost 40% of our visitors are from the NY metro area 30% from Boston, 20% from around here and the others come from all over the place. I really enjoy our audience. It’s one of the best in the world. Interesting things happen this time of year when we are doing residencies. We are showing mostly to people who live here, who by the way, are the most sophisticated audience in the world for the work of Laurie Anderson because she has made 3 or 4 of her major works of art here. It is surprising after a performance the questions that an artist like Laurie will get from our local audience. I’d put them up against questions from any audience in the world. They are experts because they come over and over again.

Natalie Jeremijenko, who made that wonderful piece out front called Tree Logic with the 6 trees hanging upside down had something really interesting to say about that. She said she imagined MASS MoCA correctly, as a place where lots of NYers, Bostonians and people from Paris come to spend time. She wanted to make a work that would privilege our local audience. She noted that over time our neighbors would become experts on these trees because they would get to watch them slowly react. The phototropic effect winning out over the gravitropic effect, leaves heading skyward and they would become acutely aware of the kind of wildlife that would build their nest in them. The piece has got privileges for people who live here and get to see these trees growing year after year. She said she thought that was a fundamental point in that work, to make a work that locals would understand better than our guests.

CH Everything I hear you saying seems to be about interaction, either with the artists, or with the people visiting, with the space.

JT You hope so. You want people to take part.

CH It seems less stagnant than most museums.

JT Our floors are not straight, they roll a little bit. We don’t have a big budget for a security force. We don’t have a bunch of people in blue blazers saying “stay off.” Our box office is friendly. There’s a kind of warmth to these buildings, the honey colored floor and the red brick, the fact that the mullions are all a little different from one and other. You don’t get the feeling that there’s one shade of gray here that’s been picked by a designer whose job is to pick the perfect shade of gray which often signals to people that this place is not for me. I hope we don’t have that.

CH I don’t think you do. Two more questions. You have been at the helm here for 15 years plus, I’m really curious, because it seems you have a bird’s eye view, of what is changing in contemporary art. What’s your take on that?

JT A lot has changed. When we were first proposing MASS MoCA in the late 80s we did a survey, we were trying to prove to the government which was going to be providing funds, that people would come. It wasn’t encouraging. When we asked people why they came to the Berkshires, art was well down the list below golf and birdwatching. And if you tuned in on art and asked people what kinds of art they were interested in, French Impressionism was of course at the top, and somewhere below suits of armor came contemporary art. We were way down on a list that was already way down. That’s changed over the last 25 years.

CH Why?

JT I think institutions have gotten a lot better about presenting art so it doesn’t seem like it’s a secret, coded club.

CH You think it is from clearer liner notes on the walls next to the art?

JT Those can still be pretty bad, but we are getting better at inviting people in and convincing people this is art just about the times we live in and it should be more interesting in a way. This is art that is about things that are of our lives. Even though the forms might at first seem remote, the topics are acutely interesting to us. More and more artists are using video obviously, and younger generations are deeply interested in it. If you go through MASS MoCA right now, fully a third of our museum is given over to works that have film or video as their base. This is particularly attractive to younger audiences who are very tuned in to this. Maybe the world has become more fluid, art changes quicker. I don’t know. I don’t have a really good answer to it.

CH So, the annihilation of the boundary between one form and another?

JT I think people are much quicker to move between fashion and theater to art and when you just flip through magazines today or go on line and look at sites like yours. What are you writing about? What are you talking about? It’s a very fluid world we’re in now. I think that’s one thing. Clearly there’s tons of money chasing contemporary art in a way that it didn’t used to. The index that the New York Times uses now to gauge whether auctions are successful — they tend to look to modern and contemporary work. Twenty-five years ago they would have looked at the Impressionists’ market as the main indicator.

CH My other question is, I’ve read about phase 3 and the additional space, but lets instead ask about what you see happening in the next 5 or 10 years?

JT My idea of Nirvana, Museum Nirvana, would be a place you could come, see a 130,000 square feet of changing exhibitions every year, the kind of programming people think of when they think of MASS MoCA, side by side with our performing arts program ranging from indie rock concerts to avant garde music and jazz, but also a series of milestone collections. These core moments like the Sol Lewitt and Anslem Kiefer installations. If there were 3 or 4 or 5 projects like that.

CH Semi-permanent?

JT Semi-permanent, long term projects that we do with other institutions, other museums, other collectors that are not MASS MoCA’s voice, that are really the voice of the artists that make them or the collectors who assemble them or the educational institutions that can catenate a program.

I love the idea of a visitor who comes to see what’s MASS MoCA’s idea of interesting art from a curatorial point of view, side by side, cheek by jowl with 6 or 7 other points of view that are represented by longer term installations that stay put and allow people to come back over and over again.

To me, when I go to the Philadelphia Museum of Art, I usually go there to see the new show, but I always go back to see the Duchamp installation, and I always go back to look at Brancusi. Those have become touchstones.

I think that really beautiful museum experiences have this kind of double edged sword where you’re seeing something new, a temporary manifestation of an idea, side by side with a milestone of important moment in art history that you can come back to over and over again as you change through life. This to me is a beautiful idea, and you layer that along with preforming arts, and that would be great museum.

CH Do you think that contemporary art, some of the installations, are only interesting once?

JT Look, every time we do a new show I think that we are about to do the most important thing we’ve ever done (laughing)!

CH Of course!

JT I’m so optimistic. I’m fit to be tied about this Teresita Fernandez exhibition that’s going on right now. I think it’s going to be exquisite, and I always think that. In retrospect you look back and some really stick in your mind as important exhibitions that I’ll remember and I know that the people that come here will remember their entire lives. Some probably won’t because the work doesn’t hold up in some fundamental way or it just was not as compelling. You never know which it’s going to be in advance. We’d be geniuses if we did. We go out and try to do really good new work every year, and I think we have a good track record.

There are brilliant experiments which fail grandly.

CH Which is a beautiful thing. You talked about building a door and bringing an airplane in, and the guy backed out of the show. I fell in love with you when I heard you dismiss that as an experiment that didn’t quite work out, but no love lost. I was really impressed with that.

JT That was obviously a difficult moment.

CH I think you got a lot of grief for that, didn’t you?

JT If you call 2 front page stories in the NY Times a lot of grief, yes. It’s almost a cliche to say to experiment truly, you have to fail, to allow yourself to fail. One thing you have to feel is as though there is a net below you because you don’t want to die. That kind of net, a safety net is in a great institution like this first and foremost a great staff around you, secondly a great board of trustees that are going to be with you so it’s your friends, the institutional family that allow the curators and the artists who go out and try big work knowing that if it all goes to hell in a handbasket, which it can do, that the world’s not going to end. Life will go on.

CH It’s a very experimental attitude. I mean even if an artist proposes something it’s not necessarily going to work out the way they thought it would. They might have to alter it as they are working in the space.

JT That’s very interesting. Because our exhibitions are up, artists will come back and change them. Izhar Patkin was just here this weekend and he did 2 new gestures on his work which had already been up for 3 or 4 months. We’ve seen it over and over again. Artists come in from all around the world making these big installations and come back and visit a time or two, and they’ll often make changes; and that’s something they don’t get to do very frequently in their most of their other creative lives, once the work exits the studio. The Museum of Modern Art, once you have a show up, they are probably not going to allow a whole lot of changes once it’s done. They’ve got a tight schedule, a rigorous production schedule. Here we’re graced with space and time.

– Taken from video interview with MASS MoCA’s founding director Joseph Thompson

North Adams, Mass., April 25, 2014