Imaginary Numbers

Daniel Barbiero

May 2021

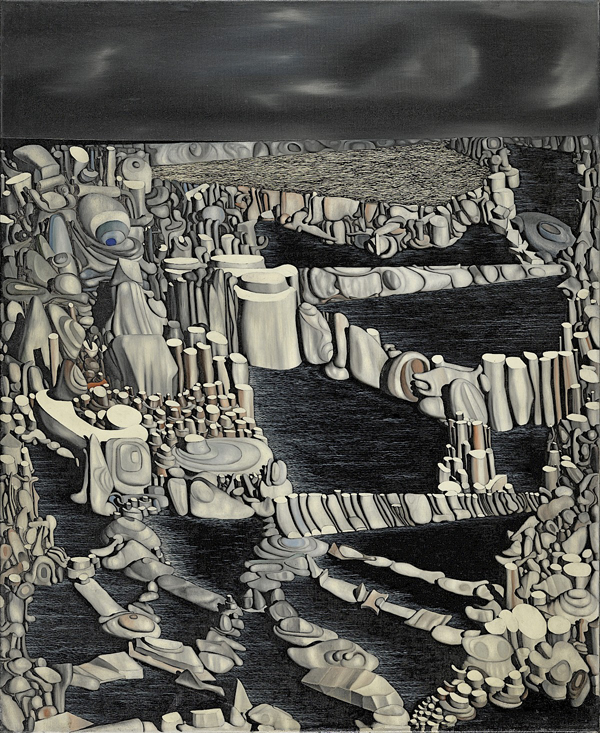

Imaginary Numbers, Yves Tanguy, 1954

Imaginary Numbers, Yves Tanguy, 1954

Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum Spain, © Estate of Yves Tanguy / ARS

New York, courtesy of Obelisk Art History.

A Quasi-Landscape of the Uncanny

A compass would be of no use here; there’s no question of getting oriented. Vanishing points seem to proliferate, cross and diverge; lines of sight lose themselves in this strange landscape of cluttered rock. We seem to have been dropped onto an uncomfortable ground of opaque bodies and hard surfaces—a labyrinth that gives us nothing to go on, or a parodic desert of broken buttes and mesas? These forms could be monumental, or they could be minuscule; partly because it is so crowded, the scale of this place is impossible to gauge. As is its origin. Are these naturally occurring piles of rock—glacial deposits, for example–or are they structures artificially, if somewhat sloppily, arranged into heaps? Here as with his other strange paintings of hallucinatory landscapes, Yves Tanguy’s Imaginary Numbers gives no answers. All we know is that we’re here, whatever “here” turns out to be.

Imaginary Numbers was painted in 1954 and may be Tanguy’s last work. Like the artist’s best-known paintings of dreamlike, ambiguous forms on what appear to be coastal plains or shallow seabeds, Imaginary Numbers is a landscape, or quasi-landscape, of the uncanny. Consistent with Tanguy’s earlier paintings, Imaginary Numbers seems to depict a strange and estranging place best described as atopos—alienating and undecidable, a place perpetually out of place with itself. It hints of a nowhere that, although vaguely suggestive of a landscape of rough geology, doesn’t seem capable of supporting real existence. To the extent that the world it depicts can only exist in the imagination, it is in line with Tanguy’s earlier scenes of biomorphic forms suspended in wide-horizoned spaces. But at this point Imaginary Numbers diverges.

What we’ve come to think of as the typical Tanguy imaginary landscape is a sparsely populated plain—a shoreline or floor under water’s edge containing living forms of some sort—perhaps some as yet undiscovered invertebrates or ocean flora. Imaginary Numbers’ atopic landscape is different. The supple, curvilinear biomorphs of the earlier paintings have been replaced by rigid, hard-edged shapes of geological or quasi-geological origin. If the forms in Tanguy’s earlier paintings seem almost weightless, if solid, the forms here are heavy and ground-bound—rounded and cylindrical, suddenly broken off at the top, they resemble petrified stumps or barren rock formations. By the same token, the relatively open spaces of the seabeds and coastal plains of the older paintings have given way to a space stifled with a suffocating density of matter. No bare ground shows through. What isn’t covered by rock is apparently surfaced by water; the scene can be read as a network of lakes or canals enclosed by stone walls. Even the color palette has changed. Imaginary Numbers is done in an oppressive range of greys, blacks and silver-blues with scattered brown highlights. “Oppressive” in fact is the best way to describe the atmosphere of the atopia the painting depicts, in dramatic contrast to the almost whimsical scenarios of Tanguy’s earlier paintings.

Metaphysical Geologies

Like Tanguy’s other enigmatic landscapes, Imaginary Numbers shows a geography situated as much in the internal world as in its external counterpart. With it, Tanguy charges the visual traces of the physical with the affective valences of his personal metaphysic, a metaphysic fundamentally rooted in dream and recollection. As with so many of those other paintings, Imaginary Numbers seems to have emerged from Tanguy’s memories of the landscape of coastal Brittany, where he spent summers at the family house in Finistère, the westernmost part of France that juts out into the Atlantic. The marine ambience of the coast permeates Tanguy’s paintings of the 1920s and 1930s. That evocation of the open vistas of the shoreline is less true of Imaginary Numbers as well as some of the other later paintings Tanguy executed, such as Multiplication of the Arcs. But Brittany still seems to be present in these pictures, if through a different complex of allusions. If they no longer contain figures suggestive of marine flora and fauna, the hard-edged, mineral-like images that populate the paintings of the 1940s and 1950s seem to allude to another peculiar feature of Brittany’s landscape–the dolmens and menhirs that, dating back to a megalithic culture 6500 years old, are found there. These standing stones would seem to find an echo in the quasi-geological piles of Tanguy’s late paintings.

But I want to suggest another possible source for the quasi-geological iconography in Tanguy’s later paintings. Some of it, to be sure, may have come from the landscape of the American southwest, which Tanguy saw when visiting his friend Max Ernst in Arizona. But another source may have been the landscape of Tanguy’s adopted home. After his move to America in 1939, Tanguy married the American painter Kay Sage and settled in Woodbury, a small town in western Connecticut. Connecticut is full of woods and fields containing old stone walls—more or less loose piles of rocks pulled from ground being plowed for farms, many of which were subsequently abandoned and allowed to revert to forest, leaving the walls behind. These stone walls are frequently encountered throughout the state and are a characteristic part of the background texture of the physical environment. It’s possible that these local standing stones, which might strike a Breton as miniature parodies of menhirs, came to Tanguy’s conscious or unconscious notice and from there made their way into paintings executed in America.

Perhaps coincidentally, Imaginary Numbers contains another suggestive allusion to the landscape of Tanguy’s adopted state. The upthrusting, abruptly truncated formations in the painting recall the bare, columnar faces of the basalt traprock ridges that run on a north-south axis through central Connecticut from Long Island Sound and reach all the way up to Vermont. In addition, the heaps of broken rock on the ridges’ talus slopes resemble the clutter of figures in Tanguy’s canvas. But although the Connecticut traprock ridges and the figures in Imaginary Numbers show a striking similarity of shape and disposition, they do have one significant difference: color. Because of their high iron content the traprock ridges feature the distinctive, reddish tinge of oxidation. Tanguy’s painting, as already noted, is composed of greys, blacks, and silver-blues—colors drawn from the opposite end of the scale.

We don’t know if Tanguy was familiar with Connecticut’s concatenation of traprock ridges. Still, it’s an intriguing possibility that Imaginary Numbers represents an oneiric hybrid of the geologies of the Old and New Worlds—of Tanguy’s childhood and adult environments—fused from that Surrealist vantage point where contradictions and incongruities dissolve. By extension, we might want to see the painting’s coincidence of forms as an example of what the Surrealists characterized as objective chance—a convergence of unlikely events or objects that carries a profound, if not immediately apparent, significance for the person touched by it. A metaphysical significance, in the sense that what is revealed is some occult truth about the reality beneath the appearance, a reality animated by affective need and expectation, and perhaps a variety of self-knowledge ordinarily unnoticed or ignored.

If what we’re seeing in Imaginary Numbers is a representation of a landscape or landscapes Tanguy knew, it isn’t a literal representation of the physical places’ features so much as a metaphysical image, one screened through the distorting lenses of dream, affect, and the variably reliable faculty of memory. Through this process of transformation perception passes from the purely empirical to the affectively meaningful and the imaginatively resonant; committed to canvas it discloses a set of complex and contraposed affective meanings entangling the recollection of roots with the atopia of uprootedness. It is in the context of these contradictory moods that the disorientation and out-of-placeness—the sense of being atopos–that Tanguy’s claustrophobic, estranging landscape hints at truly come into their own. Tanguy’s painting doesn’t give direct, unambiguous evidence of the visible places provoking this meaning but rather is rooted in a lived situation whose landmarks are the products of emotional attraction and repulsion, of need and desire, rather than of geology and erosion.

Imaginary Numbers as Poetic Analogy

Like Tanguy’s imaginary landscape, the mathematical objects known as imaginary numbers are atopos—strange and apparently not to be encountered in any actually existing world. Their strangeness consists in their seemingly self-contradictory nature: they involve the square root of a negative number, contradicting the mathematical truth that any number times itself produces a positive number, even if the multiplied number is negative. Given this contradiction, square roots of negative numbers shouldn’t exist—they should be purely imaginary, as Descartes, who gave them that name, thought–but they do in fact exist and are used for electrical engineering, probability calculations and communications applications.

In giving their name to Tanguy’s painting, imaginary numbers serve as a metaphor for the reality of what otherwise would be dismissed as “merely” imaginary. In an odd way they symbolize the ultimate point Surrealism aimed at: the point at which the contradictions between dream and waking reality, consciousness and unconsciousness, and perception and imagination, would dissolve. It is a point Tanguy’s imaginary landscapes, with their metaphysical overtones, approach. To the extent that Imaginary Numbers depicts a geology with metaphysical overtones, it stands as the image of a reality transposed to and revealed by the affective realms of dream and memory—an image that, in the best traditions of Surrealism, appears to refuse the constraints of the real, but only for as long as the latter is understood to be coterminous with the plain, unmetaphysical world of mute things and meaningless events. But like imaginary numbers, whose reason for being initially seemed to consist in their impossibility of being, Tanguy’s imaginary geology doesn’t refuse reality—or better, is not refused by reality—so much as it represents a reality permeated by the super reality of human purpose as manifested through the filter of affective meaning. Like imaginary numbers, Tanguy’s imaginary rockscape turns out to have a real existence and to that degree, its title serves as what André Breton, in his essay “Ascendant Sign,” defined as a poetic analogy: a means of comprehending one thing through another by virtue of a relationship between two objects of thought from different planes that, through a kind of non-logical apprehension, reveal themselves to be somehow interdependent. Taken as a poetic analogy, imaginary numbers demonstrate the interdependence of the imagination and reality—or put in other terms, of the physical and metaphysical—an interdependence the recognition of which allows the portending coincidences of objective chance to be recognized and deciphered.

Anxiety & Anticipation

As Michel Carrouges points out in his study of the basic concepts of Surrealism, objective chance has a “dark zone” disclosed as a presentiment that may make itself known through feelings of panic, anxiety and estrangement. This dark zone derives from the way objective chance appears to upset the uniquely human mode of temporality—the projection forward into a future that may or may not be. Rather than presenting a future of possibility (and the possibility of failure), objective chance as the occasion of presentiment appears instead to be revelatory of destiny; read that way, the coincidences it consists in seem to point uncannily toward an already accomplished future, which it hints at through its disquieting intimations of what (apparently) necessarily must be. Such a reading would be too superficial, however, and deeply misleading. The destiny objective chance reveals isn’t something preordained and always already accomplished but instead is a conditional destiny, one contingent on the person to whom it attaches. To a reasonable approximation it is the kind of destiny that Heraclitus, as he’s often been translated as saying, framed in terms of one’s fate (daimon) consisting in one’s character (ethos)—a destiny in the form of a likelihood dependent on one’s own pattern of actions, desires, limitations and self-knowledge (or ignorance) that requires the right convergence of events for its realization.

If objective chance is a function of the existential structures unique to a given person, then, as Surrealism would seem to have had it, it could be expected to disclose itself through that person’s unconscious (however defined) by way of automatic writing or visual imagery. These latter media would provide what Ferdinand Alquié, in The Philosophy of Surrealism, described as “poetic flashes [that] come to enrich human experience in the manner of premonitions” (p. 97). Just such premonitory flashes would appear to be embodied in Imaginary Numbers, whose atopic atmosphere may derive from something over and above its apparent allusions to dream and memory. It may derive instead from the anxiety that often accompanies anticipation.

Anticipation, in the form of a sign of a coming event, can be read in the sky above Imaginary Numbers’ rockscape. It is thick with bilious black clouds gathered in rolls, the kind of sky that precedes a storm or tornado. In light of the fact that the painting, completed shortly before Tanguy died suddenly of a cerebral hemorrhage in January, 1955, was probably his last, the sky reads less like the neutral depiction of certain meteorological conditions than as an omen. Not only does the sky seem a sign of impending death, but the truncated cylindrical shapes of the rock formations bear an uncanny resemblance to broken columns–a form of funeral architecture used to memorialize someone dying suddenly or in the prime of life. (Interestingly enough, in his 1927 painting Death Watching His Family, Tanguy included as a central image a short, stout, apparently stone cylindrical form that appears to be a broken column.) When read this way, Imaginary Numbers begins to resemble the cloud-overshadowed landscape of a cluttered urban cemetery.

If dream and memory present the empirical facts of experience through the filters of affect and need (or desire), anticipation projects affect and desire forward onto facts of experience that have yet to be, if they are to be at all. It is through such anticipation, Surrealism held, that objective chance would allow itself to be perceived. But in the end, what anticipation opens up to, and what objective chance can be said to reveal, beyond the specific events that may appear destined for any given individual, is the ultimate nothingness of fate–the abyss over which human existence is constructed. There is thus an irreducibly tragic dimension to objective chance, no matter how marvelous its outward manifestation. With its claustrophobia-inducing labyrinths dead-ending, metaphysically speaking, at this zero point of nothingness—a point where dream, memory and premonition converge–Imaginary Numbers follows objective chance to its ultimate conclusion.

Works referenced:

André Breton, Ascendant Sign, in Free Rein, tr. Michel Parmentier and Jacqueline D’Amboise (Lincoln, NE: U Nebraska Press, 1995).

Michel Carrouges, André Breton and the Basic Concepts of Surrealism, tr. Maura Prendergast (University, AL: U of Alabama Press, 1974)

Ferdinand Alquié, The Philosophy of Surrealism, tr. Bernard Waldrop (Ann Arbor, MI: U of Michigan Press, 1965)

◊

Daniel Barbiero is an improvising double bassist who composes graphic scores and writes on music, art and related subjects. He is a regular contributor to Avant Music News and Perfect Sound Forever. His latest releases include Fifteen Miniatures for Prepared Double Bass, Non-places & Wooden Mirrors with Cristiano Bocci and In/Completion a collection of verbal and graphic scores by composers from North America, Europe and Japan, realized for solo double bass and prepared double bass.