Heat into Light

Amy Pratt

February 2017

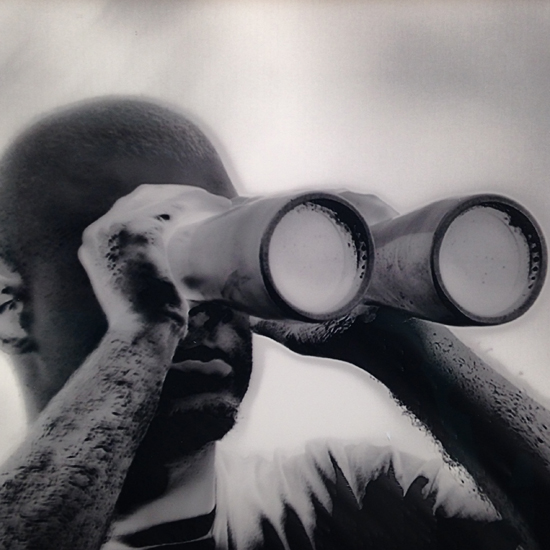

Still from Incoming #85, image courtesy of Arteidolia

Still from Incoming #85, image courtesy of Arteidolia

First, I thought, Caravaggio. Chiaroscuro. The mystery of a universe of light and dark forces had been made alive again. As if I was looking at a spectral expression of the state of the soul in the twenty-first century. What was I seeing? From afar, only a huge black and white photo, aglow with eerie white lines dwarfed by boxy, abstract shapes of gray and black, set against desolate mountains and sky. It had the texture and look of images on a negative. Yet different. So different. For, the quality of light, almost florescent, seemed to vibrate, like cilia on the walls of a hundred thousand cells. A radiation of life. Present, yet invisible, to the naked eye. Which was, in a way, just what it was.

It was heat photography. I realized that soon enough. I had seen it done before. But what Richard Mosse is doing with his show, Heat Maps, is new. And significant. For this work draws together form and content, revealing both the technology’s military roots, and the culture it both reflects and projects.

I stepped closer and slowly began to make out the depicted human scene. It was some kind of encampment: there were structures, streets, trucks; a makeshift village foregrounded on a treeless plain. Then, another visual paradox struck me. The photographic textures were incredibly rich, yet this was clearly an impoverished world, a place stripped to the bare essentials. A mining camp? A military encampment? Any place that was no place. I let myself be mystified for a little bit longer, to take in the beguiling clarity of the bright darkness.

closeup from Moria in Snow, 2017, image courtesy of Arteidolia

closeup from Moria in Snow, 2017, image courtesy of Arteidolia

The photos reminded me of the pictorialists’ use of light in the early twentieth century. And especially of László Moholy-Nagy’s famous self-portrait. (I would go home and look him up, and think a long time about how the dots connected: Caravaggio, Moholy-Nagy, and now, Richard Mosse).

The informational sheet that accompanies the show confirmed my final guess about the places in the photographs. They were refugee camps which, among other related images, are all part of a series Mosse has made to document the journey of migrants and its many meanings. Here he has focused on the two busiest refugee routes. One leads from regions around Syria, through Turkey to Greece. The other is a trail through Africa, north to Calais (the camp that was closed in October, 2016.)

The visualizing techniques of the heat-sensing camera have been developed by the military for surveillance purposes. It is a tool, but it is also a kind of announcement about the arrival of a new world order, symbolized by, and embodied in, the migrant. Mosse explains the project, and the story of how it came about, in an essay (available at the gallery) from his book Incoming, published by MACK, with an accompanying text by philosopher Giorgio Agamben.

We were trying to work the technology against itself, to brush it against the grain. But we weren’t attempting to rescue this apparatus from its sinister purpose. Rather, were trying to enter into its logic – the logic of proprietary government authorities – to foreground this technology of discipline and regulation, and to create a work of art that reveals it.

Two things will keep you up at night. First: this camera can record events miles away. Mosse describes standing on a hill and watching, though the screen, a battle taking place 10 km away.

We were able to see entire buildings on fire beneath glimmering minarets, the slow arc of mortars launched, rockets tracing the sky. By following the missile’s path, we could detect hidden artillery positions, and watch columns of fighters spreading out across fields, utility pickups with armored turrets and the twin black flags of IS.

But Mosse also discovered that, although the camera unquestionably exploits a technique of “dehumanization” it also has an ironic, humanizing side.

The extraordinary long range nature of the lens allowed the image to telescope far beyond what is normally possible. This invasive gaze, capable of zooming in on people unawares, enabled an unusually candid kind of portrait, free from embarrassment, posturing, or self-consciousness. A kind of tenderness resulted. A tenderness without privacy, made anonymous.

Underscoring this, he ends the essay with a story which culminates in an unforgettable image. A migrant who clambers out of a truck to pee. He then carries out an ablution ritual before beginning to pray.

His index finger swayed from side to side, almost from muscle memory, as he recited a prayer to himself. A remarkable sense of rapture emerged on his tired face. It was completely untainted by self-consciousness, or seemingly even self-awareness. It was like he was drifting away before our eyes – like all his worldly struggle, the fear and pain he endured on this terrible journey, began to demateralize, leaving him standing there exalted, staring blankly at us in total darkness, with an emotion written on his face that I had never expected to see, and will never see again.

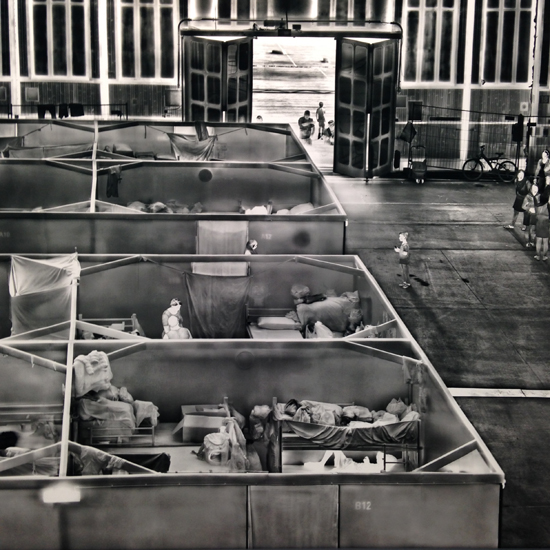

closeup from Tempelhof Interior, 2016, image courtesy of Arteidolia

closeup from Tempelhof Interior, 2016, image courtesy of Arteidolia

Mosse’s essay is entitled, Transmigration of the Souls, pointing somewhere in the direction of this moment, as if following that inward gaze—perhaps, a gesture of hope. Yet, what is underlined in this show is the way this new bio-technology, perhaps like no other before it, represents a paradigm change in how we understand our place in the world. And it’s impossible not to feel that we will need all the hope we can muster to see our way through.

Caravaggio’s paintings also emerged at the beginning of a new way of understanding life and death. The reformation had just let loose its radical new ideas about what individual men (it was only men) could and couldn’t know about themselves, their world, and their role in the universe. Its new faith in reason enabled the world to become a tool, and with it, a chance to give life an edge over death. It was perhaps against this optimism, and the style of mannerism that was so intellectually sophisticated and unnaturally elegant, that chiaroscuro emerged, introducing a naturalism that wants to keep hold of the body and its dark, mysterious, emotional depths.

And it’s not a little heartbreaking to ponder Moholy-Nagy, at yet another turning point, a moment somewhere between the Renaissance and the twentieth-first century, when the machine age reached a new maturity and it seemed like it just might be possible to parse infinity into a chronology of forward moving steps, led by the light of reason.

The twentieth century cast much doubt on that idea. And now this. The new perspective that Mosse shows us is a double-vision; it reveals both the material body in a particular time and space–an identity now easily blasted to bits–and an infinity of other energies in a cosmos that defies our comprehension.

That, more than anything, is what we are given to see: a field pulsing with heat and light into which all individuality explodes into nothing but the dark force of power, with only traces of life. But the technology can also make visible the great multitude of living things, and that, and the beauty of these photographs, left me with some space to wonder whether we might just yet keep the scales tipping away from death and back towards that life.

closeup from Idomeni Camp, Greece, 2016, image courtesy of Arteidolia

closeup from Idomeni Camp, Greece, 2016, image courtesy of Arteidolia

Richard Mosse

Heat Maps

Jack Shainman Gallery

513 West 20th Street, NYC

February 2 – March 11, 2017