Exchanging Field Notes

Catherine Henke

Randee Silv

February 2018

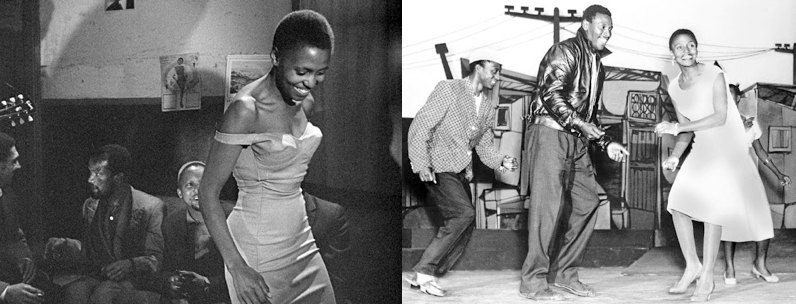

scenes from Come Back Africa and King Kong

scenes from Come Back Africa and King Kong

“I do not sing politics. I merely sing the truth.” I recently saw Mika Kaurismäki’s documentary on the life & music of Miriam Makeba, Mama Africa. Getting black artists out of the country was almost impossible, so New York filmmaker Lionel Rogosin had to bribe officials so that Makeba could attend the premiere of his 1959 anti-apartheid film Come Back Africa at the Venice Film Festival. In order to accurately portray the lives of black South Africans, it was made in secret with non-professional actors and had to be smuggled out without official consent. In Makeba’s cameo, she sang two songs in a shebeen, an illegal bar. Under the 1927 Liquor Act, non-white South Africans were prohibited from selling alcohol or entering licensed establishments. When Miriam was 18 months old, her mother was arrested for illegally selling the traditional homemade beer brewed from malt & cornmeal, umqombothi. Unable to pay the fine, she & Miriam spent six months in jail.

In the first all-black musical, King Kong, which was about the rise & fall of heavyweight boxing champion Ezekiel Dlamini (set in Johannesburg’s Sophiatown, a thriving, culturally rich black community that was forced to relocate to government run townships), Makeba played his girlfriend, a shebeen queen. The 1959 play was a huge hit with record breaking multi-racial audiences. The South African government saw Makeba’s international success as a threat. Her passport was stamped “invalid” by the consulate in NY when she requested to return home for her mother’s funeral. She lived in exile for three decades until Mandela became President. After Makeba married Stokely Carmichael in ’68, she found herself being boycotted by the American music industry. Carmichael had asked questions in his 1966 “Black Power” speech like “can white people move inside their own community and start tearing down racism where in fact it does exist?” and, “how can white people who are the majority–and who are responsible for making democracy work–make it work? They have miserably failed to this point.” Makeba was hounded by the FBI, her concerts cancelled and records pulled from the shelves.

Dear Unsuspecting Public, Jimmie Durham is a Trickster, an editorial on Indian Country Today in response to his traveling retrospective, At the Center of the World, has been stirring debate. Points addressed are that Durham’s “indigenous identity has always been a fabrication,” that he is “not a Cherokee in any legal or cultural sense.” and that “these false claims are harmful as they misrepresent Native people, undermine tribal sovereignty, and trivialize the important work by legitimate Native artists and cultural leaders.”

Under mounting scrutiny, The Walker Art Center, The Hammer and The Whitney museums have since added disclaimers to the exhibition’s web pages, though it will probably not be seen by most of the visiting public. Durham has gone back & forth over the years alternately stating that he is and isn’t from the Wolf Clan. The art world has been accused of enabling this position. The Whitney Museum sees it as a “platform for discussion and dialogue,” but I didn’t get that feeling when I was there. I didn’t notice anything posted anywhere.

“I do not sing politics. I merely sing the truth.”

The truth is a big word, the kind of word you don’t know where it starts and where it ends. I prefer when she says the songs that I sing are just about my everyday life, it’s my way to express that we have to fight and liberate ourselves. Makeba also said something beautiful about her community, her people, that they are happy, they smile, they play music, they dance… she said: “sometimes it’s better to love to keep from crying.”

Come you masters of war

You that never done nothing

but build to destroy

you play with my world

like it’s your little toySo let’s discuss about life

“Life is like stepping in a boat that is about to sail out to sea and sink.” – Shunryu Suzuki

As long the journey lasts… enjoy it, it means that you are alive.

Now let’s discuss about what’s real and what is not.

There were Czechoslovakian students in Geneva at that time who were running away from the invasion of Czechoslovakia (1968). Jimmie Durham pretends that he had studied at the École des Beaux Arts in Geneva in 1969. I was studying there at that time. The school was small and everybody knew each other. I never heard of any Jimmie Durham. And why would a Cherokee Indian go to study art in Geneva? Right, he isn’t a Cherokee Indian.

They are many here among us

who feel that life is but a joke

but you and I have been through that

and is not our fate

so let us not talk falsely now

the hour is getting late.how many roads must a man walk down

before you call him a manthe answer my friend is blowing in the wind

the answer is blowing in the wind.from Bob Dylan’s Masters of War, Gates of Eden,

All along the Watchtower & Blowing in the Wind

I double checked some art sites, and they all repeated the same information about Durham. He went to École des Beaux Arts in ’69, graduated in ‘73 and, with 3 other sculptors, formed the group Draga. (Catherine: Yes, very strange about JD. I was at the school from 1968 till 1972. I never met him. Never heard about this group Draga.) I have a friend that said he was Cherokee, but he and we knew he wasn’t. Have you ever thought about being someone you weren’t?

I’m not sure it’s the same thing as when Vosdanig Adoian decided to reinvent himself as Ashille Gorky, a Georgian Prince and student of Vasily Kandinsky. Or, when he was referred to, in a 1926 New York Evening Post article about his appointment to the Grand Central School of Art faculty, as “a member of Russia’s greatest artist families, for he was a cousin of the famous writer, Maxim Gorky.” Or, being identified as “American, born Tiflis, Russia, 1904” in a 1944 MoMA catalogue.

His wife Mougouch had no idea he was Armenian until after his death. Gorky remembers his village as a “magical place,” where all his “vital memories” came from, where he “smelled the bread” and saw his “first red poppy, the moon, the innocent seeing” and not the genocidal slaughter and forced exile during the 1915 Siege of Van by the Turkish government who saw Armenians as a treat to their empire.

An undated fragment written by Gorky:

Welcome O talent! Our ancients accepted only the best.

Our precious lives are consummated.

O talent! Our present culture is frustrated.

I think our lives flow like a molten lava.Mougouch noted at her parents’ Virginia farm, summer of ’44:

Today he is heart broken because the farmer has cut the weeds to let the grass grow for the cows & all looks too park-like for Gorky who loved the purple thistles & great milkweeds & ragweeds – Poor dear he always gets slugged – He stood on the hill watching the tractor down in the bottom land moaning `They are cutting down the Raphaels…`

Arshile Gorky, The Plough and the Song, 1947 & Water of the Flowery Mill, 1944

It’s a fairly common practice in the history of art to adopt an artist’s name (pseudonym). Artists often change their name to express a modification in their life. The artist’s name or brush’s name is a pseudonym used by the artists of Far East. The Japanese painter Hokusai, for example, used more than 55 different names in his whole life, changing his name for each new important work of art.

The whole creation of a new biography is not so frequent, but necessary to some artists to cover up a difficult phase of their past, to create new relations, to create more impact, more attraction. It’s a piece of art in itself.

I read recently the novel of Vladimir Nabokov called: The Real Life of Sebastian Knight in which the narrator strives to write a biography of his brother, Sebastian Knight, a brilliant novelist, who had just died. His writing, like a reinvented biography, is based on some memories, on the work of his brother and on testimonies of people who have been close to him. In this book, Nabokov mixed details of his own life with others that he completely remade. The real life reveals the real problem of the ambiguity of human identity. “Remember that what you are told is really threefold: shaped by the teller, reshaped by the listener, concealed from both by the dead man of the tale.”

The book offers an interesting reflection about the impossibility of knowing another being, even if very close. The book ends with these words: “I am Sebastian or Sebastian is I, or perhaps we both are someone whom neither or us knows.”

Click for Field Notes: Sea Voyages Within A Precious Stone

Field Notes: On Raku & Cork

________________________________________________________________________________________________

Visual artist Catherine Henke, originally from Geneva (Switzerland), chose to live and work in Montemor-o-Novo (Portugal).This radical change in her living conditions encouraged her to learn about rural life and the practice of organic agriculture. She has developed knowledge related to the rhythms of nature and to an ecological consciousness. Her art practice comprises varying uses of numerous techniques, such as painting, sculpture, ceramic and mixed media installation.

To read more by Catherine Henke, click here

Abstract painter Randee Silv is the editor of Arteidolia and swifts & slows: a quarterly of crisscrossings. Silv also constructs wordslabs that emerge as gestures reshaped, juxtaposed, tilting fragments that alter between what is and isn’t. They have appeared in Posit, Urban Graffiti, Maudlin House, Sensitive Skin, Bone Bouquet & Otoliths. Her chapbook, Farnessity (2018), has been published by dancing girl press.

To read more by Randee Silv, click here