Eruption of the Text in the Turbulent Sign

Carl Watson

June 2017

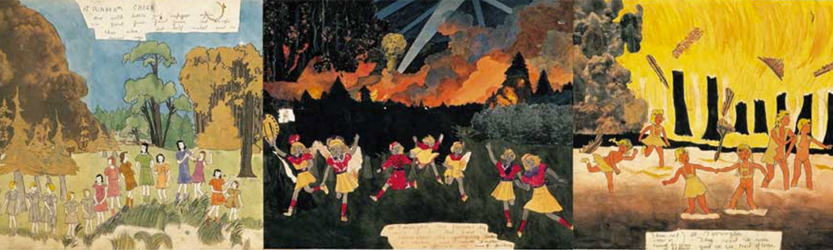

At Sunbeam Creek, image courtesy of Wikiart

At Sunbeam Creek, image courtesy of Wikiart

Eruption of the Text in the Turbulent Sign:

Ink Blobs, Doodles and Inadvertent Illustration

I have been involved in a study of Henry Darger’s writings for some time. My primary focus has been his autobiography The History of My Life, and the main mode of analysis for this book has been to study it in terms of non-linear fluid dynamics. This involves closely tracking the way the text repeats itself in theme and image over the course of 5000+ pages and then to determine what can be learned from such a text analyzed in this manner. While there are many issues to look at, this present article will examine the nature of Darger’s repeating marginal doodles and what they might mean in the greater context of his work, especially his “use” of redundancy as an organizational strategy. But first a brief description of the book and its content is in order:

The History of My Life is Darger’s “autobiographical narrative.” It was the last of his major texts, begun around 1968 and continued until shortly before his death in 1973. Like all of Darger’s manuscripts, it might be seen, physically, as a work of art brut bookmaking, being constructed of school composition and record books of different sizes, which are tied together with twine to make eight “volumes.” The last page in the manuscript is numbered 5,084. However, due to the circling back and consequent doubling and tripling of sequences of page numbers—the bound texts may be closer to 5,500 pages. Except for the first 206 pages, the story consists primarily of redundant scenes and descriptions concerning an apocalyptic tornado (at one point named Sweetie Pie) that ravages various cities in Central Illinois in or around 1906.

After reading the whole thing, I concluded that the best way to organize the material was by content: so the manuscript may be usefully divided into five sections, or books, based on primary subject matter: Prologue (separately numbered, 1-36) These are biblical citations and have little to do with the later material, but they are connected in terms of their biblical context as well as by Darger’s personal interest in numeration. Book One: Autobiography, (1–206): Darger’s narrative of his own life up until the time he retires. I will describe this section in greater detail later in this article. Book Two, Moskoestrom (206–1809): Darger’s narrative of his initial encounter with the great tornado. This book begins in the voice of Darger remembering himself as a young boy, although he quickly becomes an adult wielding both authority and expertise. He is not the only narrator, however, as the section utilizes a great many eyewitness accounts by farmers, railroad engineers, town folk, etc. I call this section the Moskoestrom because large parts of the story are borrowed from Poe’s tale “Descent into the Maelstrom“. Darger uses the Norwegian word—Moskoestrom as a name for the storm, (the Moskoestrom is a real, naturally-occurring whirlpool in the ocean between the islands of Moskoe and Moskoenas). Book Three, Inferno (1810–2950): The narrative of the Great Wheat Field Fire. The fire and its effects are often referred to as an “inferno” and occasional references to Dante are made throughout. The fire is believed to have been started by the tornado, but it is eventually found to have been set by arsonists. Much of what is described here are battle scenes, strategies and logistics as the fire expands to apocalyptic proportions. There are also discussions of dangerous clouds of smoke and of the “smoulder,” the underground fire that keeps erupting to the surface in new conflagrations. Throughout this section, Henry is an adult and a master firefighter, although numerous other voices narrate events. Book Four, Sweetie Pie (2951–5084): The narrative returns to the story of the tornado, which soon takes on the name Sweetie Pie and the anthropomorphic shape of a strangle-headed child cloud. The section alternates between eyewitness accounts of the tornado, panel discussions, and mock trials, as witnesses try to understand the meaning of this event.

Most scholars consider My Life as two distinct narratives, one being the autobiographical material and the other being the tale of the tornado. For the purposes of the present study, it is more valuable to treat the entire manuscript as a unit. Darger’s intentions in this respect are open to question. In his concurrent diary, he indeed states that the story of the tornado, Sweetie Pie, is fictional. But he continues to use the page heading History of My Life (or My Life History, or Life History) for nearly two thousand pages. We can conclude, therefore, that on some level Darger felt he was writing the same book he had begun.

At this point I would like to address the Autobiography section. This is Darger’s narrative of his own life and it is largely factual, if far from comprehensive. The artist, who seems to claim both a German and a Brazilian identity, tells an unfocused tale of a strange and sometimes brutal childhood followed by an adult life of mundane work. All this is interspersed with personal reflections. The reader gains basic chronological and logistic information—along with indications of Darger’s general interests: storms, fires, petty disputes, and personal pains. One may also detect a certain emotional distance, or matter-of-factness, partially attributable to his advanced age at the time (he was in his late 60s). What is obvious is that the Autobiography does not fulfill the typical function of autobiographies as we usually think of them—that is, the portrait of the well-lived life, the reflective life, the life atoned for. Events that normally would seem important, traumatic or life-changing are passed over with little comment. The reader begins to suspect that much of what is most important is only hinted at or actually absent, lending the narrative a tone of triviality or at least evasiveness, as if the author were hiding, rather than revealing, the relevant truth.

There is, as well, a circular movement to this part of the text, a continual chronological backtracking. In fact, much of the second half of the Autobiography revisits past themes or forgotten events; these are generally introduced by Darger as something he “forgot” to mention before. This pattern is repeated until the final return to the forgotten past which occurs on page 206. In the last sentence of the Autobiography, Darger writes: “There is one really important thing I must write which I have forgotten.” Here Darger turns to his tale of the fictional tornado that will take up the rest of the manuscript. It is some time, however, before the reader might understand that this is not, in fact, a real event; it is rendered as if part of an autobiography and may have a historical foundation, however, it becomes more exaggerated and absurd as the story goes on. The storm goes by various names (the Moskoestrom, the Oliver Twist, the Tongue) until it eventually takes the shape of a “strangle-headed child cloud” called Sweetie Pie.

I went to the window and saw a vast cloud shaped like a little girls head

turned sideways […] Hand shaped clouds were attached to the neck as if

strangling the child […] The neck seemed to squeeze in, the tongue

protruding more out […]Where the tongue protruded there was a sort of

coughing and half choking sound […] at the same moment I perceived the

strange almost human naked shaped body of the child-formed cloud was

rapidly changing into an odd churning current […] Even while I gazed the|

face seemed awfully contorted, the strange current acquired a monstrous

velocity. (3160-3161)

The combination of the circular backtracking of the text as well as the repetition of certain themes, such as rage and destructiveness are patterns in the Autobiography that will be expanded in the following three books in extraordinary fashion.

The narrative of the last three sections, (Moskoestrom, Inferno, Sweetie Pie) is composed of seemingly endless descriptions of the massive death and destruction this wild turbulence wreaks upon city and countryside alike—savaging zoos, orphanages, supermarkets, and convents. Windmills warp through the sky like flying skeletons, great municipal buildings explode, and bridges buckle like cardboard. The storm ignites thousands of acres of wildfires, which in turn create sinister smolders sending forth poison clouds that spread for hundreds of miles. (Among many other influences, the book is flavored by the cold war propaganda and the atomic bomb scare of the 50s and 60s and the poison clouds might symbolize radiation poisoning). Darger’s witnesses recount the massive movements of men and supplies across ravaged landscapes, applaud the bravery and suffering of entire populations, attend the musings of professors, engineers, and meteorologists, and stand in judgment at the trials of traitors and arsonists, culminating in the surreal trial of Sweetie Pie herself. Throughout this story, Henry Darger, the character, takes on many roles: heroic child, rescue worker, master firefighter, professor, engineer, philosopher.

Despite its sensationalism, the writing develops no climax, no conclusion, nor any real insight or dramatic tension, but seems to exist only to perpetuate itself, or perhaps it would be better to say perpetuate a “self.” But that might be exactly the point. I previously mentioned that my interest in Darger’s manuscript is framed by the idea of turbulence as an organizational strategy. We can read The History of My Life as an epic tale of turbulence and the effort to recreate order, not just an order to the world, but an order to Darger’s identity within that world, which is to say turbulence becomes a strategy by which Darger orders his own sense of self.

The narrative of My Life is full of redundancy and turbulence: time is relentlessly cyclical, events fold in on one another, geography is impossibly fluid, and it is difficult to know who is narrating at any given time. The text forms both small and large cycles of repeating language use, imagery and narrative events. In order to clarify this, I established different orders of redundancy, which include, in ascending order, the seemingly needless repetition of—letters, words, phrases, paragraphs, descriptive sections, and whole story units. Some of this repetition may be intentional and some of it may not be. But this layering of redundancies, this self-similarity of the text across its narrative scales is consonant with the whole of Darger’s work. His paintings also include a great deal of repeated imagery from painting to painting, clusters of images and thematic elements that frequently recur.

At Jennie Richee Assuming Nuded Appearance, image courtesy of WikiArt

At Jennie Richee Assuming Nuded Appearance, image courtesy of WikiArt

I now would like to switch the discussion to the doodles that I mentioned earlier in this article, and how we might read them as part of an overall strategy. But to do so, we must see them as having an intention, even if it is a hidden one. Those familiar with Darger’s visual works will know that they are closely linked to the mythology of The Realms of the Unreal, and they effectively function as illustrations of that epic. However, unlike The Realms, My Life has no accompanying illustrations, and yet, within the manuscript there exist a series of repeating, mutating doodles that could be considered a type of illustration. To think of a doodle as an illustration may seem like a stretch, but I will make an argument here to illustrate my point.

A doodle is normally thought to be a one-off: a form of graphic vamping, either indeterminate and inconsequential, or determinate and functional, such as in the covering-up or camouflage of a textual mistake. Whether determinate or indeterminate, the doodle can be read as a kind of transitional structure or process occurring within the flow of a meaning (the text) of which the doodle itself is generally not a sign. Darger’s doodle, I believe, is a sign, and it can be considered as another instance of the redundant patterns/themes that occur not only in My Life, but across the field of his work. Like other redundancies, it acts as, or points to a type of structure in the mass of chaotic material of the text. When speaking of Darger’s intentions, of course, one can only speculate. But speculation can lead to insight.

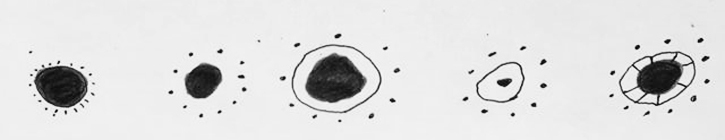

Throughout My Life, this doodle appears as a central black dot or blob (an abyss or central density) surrounded by a ring of smaller dots. This shape is modified over the course of the manuscript by the occasional appearance of a solid ring either interior or exterior to those smaller dots. Sometimes there is a series of radiating lines connecting that solid ring to the central dot. The only other variation is the weight and thickness of those elements. The doodle appears randomly on various pages throughout the manuscript, with its earliest occurrence at page 1953. Some 100 instances follow with more or less increasing frequency, achieving the greatest concentration in the page-range of 4,800—4,900.

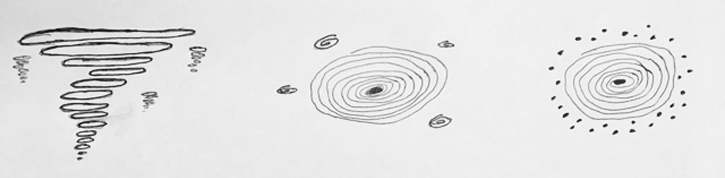

Examples of Darger’s doodles from History of My Life redrawn by Carl Watson

Examples of Darger’s doodles from History of My Life redrawn by Carl Watson

Here, I want to address the question of intent. It is, of course, possible that Darger is merely blotting out a word or letter, although this generally does not seem to be the case. It is also very likely that the doodles simply began as blobs of fountain pen ink. I do not discount this, but what is important is that Darger manipulates the initial accident or impulse into a consistent symbolic shape. I think, therefore, that we can assume that this shape has some emotional valence for him, which we can best apprehend by comparing the doodles with other examples of Darger’s obsessive imagery. People who are familiar with his paintings will recognize the following three categories of repeated / obsessive imagery: 1) flowers, especially large gaudy flowers, 2) explosions / mushroom clouds, and 3) thunderstorms / tornadoes. I will now address each of these categories of imagery.

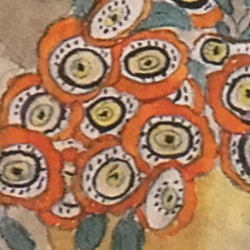

1) Flower. Darger, of course, was fascinated with flowers and many of his paintings are filled with overlarge and often primitive-looking flowers that populate some of the more bucolic landscapes. We might assume that Darger’s fascination with the flower motif arises from an attraction to an Eden-like innocence, but what is also noteworthy is the often aggressive size and proliferation of flower forms where they do occur, giving them a certain threatening aspect; and indeed they do, on occasion, accompany scenes of extreme violence. The narrative of My Life is primarily one of destruction and violence, thus if we think of the doodle as a flower of ink sprouting randomly in the fertile field of the violent text, then indeed it resonates with the flowers that fill his paintings.

Reflections of Darger’s doodles

Reflections of Darger’s doodles

appearing within his depictions of flowers

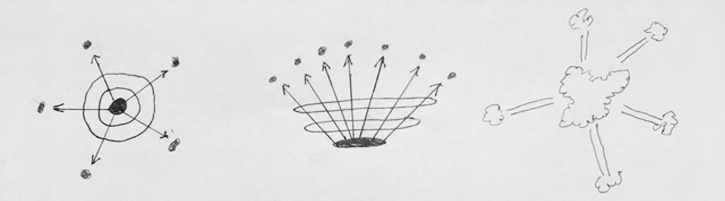

2) Explosion or Eruption. Darger’s doodle can also be read as a diagrammatic representation of an explosion, showing the outward radiation of lines of force and/or particle distribution. Darger’s painted works are filled with explosions—explosive atmospheric events, such as thunderstorms and lightning bolts, or explosive terrestrial events, such as volcanoes, bombs, etc. This explosive quality also permeates Darger’s texts, especially The Realms of the Unreal and The History of My Life. Darger scholar, John M. MacGregor, has written: “Underlying Darger’s history of a world at war is a more disturbing vision, of the earth itself grown unstable, and of the laws of man, of God, and even of nature, ceasing to hold. . . . Ultimately, the Realms, and indeed all of his writings, are dominated by portrayals of nature run amok, of the earth in Upheaval.” (Henry Darger: The Realms of the Unreal, 439). My Life is filled with descriptions of bursting buildings, exploding skies, eruptions of fire, etc. In fact, Sweetie Pie herself is often described as a: “strange shaped sideways choking child head [that] exploded itself into that sort of a tornado” (3253). Thus the doodle, as it appears in the text of My Life, could be seen as an eruption of forces hidden within or beneath the textual impulse, whereby the physical ink of words in punctuated by a sign of the emotion that underlies them.

Left to right: Diagram of explosion and distribution of debris, same explosion seen from the side,

Left to right: Diagram of explosion and distribution of debris, same explosion seen from the side,

copy of an explosion in a Darger painting. Drawn by Carl Watson

3) Storm/Tornado/Sweetie Pie. Perhaps the most obvious interpretation of the doodle is as an abstract or diagrammatic representation of the storm that the text describes. Hurricanes or cyclones often spawn tornadoes in their outer spiraling arms. Tornadoes themselves may be accompanied by smaller incomplete vortices (little tornadoes). Darger was not unaware of this phenomenon, and on more than one occasion he describes Sweetie Pie as a large vortex surrounded by, or created by, or creating smaller attendant vortices: One description claims that the tornado forms when “the gyratory of the subsided vortices […] form[s] the germ . . . of another more vast” (3039). In one instance, the tornado, Sweetie Pie, is described as composed of twelve smaller apostolic tornadoes. Seen from above, such a storm might appear as a circular rotating figure with a defined center, surrounded by smaller vortices. Thus the doodle may inadvertently act as a sort of mini-tornado illustration randomly appearing in the vast text of the tornado narrative.

Left to right: Diagram of tornado with smaller attendant vortices, same tornado seen from above,

Left to right: Diagram of tornado with smaller attendant vortices, same tornado seen from above,

tornado with circling peripheral debris. Drawn by Carl Watson

Each of the above symbolic interpretations—flower, explosion, tornado— share certain common qualities: 1) Explosive dynamic: be it biological, chemical, or as Darger calls the tornado, an explosion of air. 2) Vortical organization: the whorl of the flower, the vortices of air caused by the bombs turbulence, and of course the tornado itself is a vortex. 3) Transitional bridge between two states of being: between seed and reproduction, between containment and dispersal, between turbulence and dissipation. Without going into the details of this analysis, I highlight these qualities in order to demonstrate that each of the three forms—flower, explosion, vortex—exist in service to the universal pulse of order and disorder, and this pulse, this consistent proximity of opposing conditions, is one of Darger’s obsessions. We only need to look at the constant juxtaposition throughout his work of war and beauty, catastrophe and innocence, fragmentation and integrity. Darger is fascinated by what could be called the sublimity of transition, and it is through the repetition of transitional shapes that he, in a sense, takes up aesthetic arms against chaos in the service of order.

Indeed, when we think of Darger’s painted works we often first think of them as a series of obsessive repetitions, image clusters that repeat themselves across the field of his work. The repetitions, are in a sense, what binds the work to our memories as pictorial, linguistic, thematic wholes. Thus, beyond whatever emotional or symbolic interest these redundant clusters have for Darger, they also serve as a structural strategy, allowing the totality of his painting to achieve a certain narrative coherence, much like the refrain of a song, or the leit motif of a symphony. Rhythmic, mimetic devices, when repeated often enough, help to both create and maintain knowledge out of chaotic perceptions— they seek to contain or focus the disorder by providing a consistent, repeating ground. In a parallel manner, in fluid dynamics, emergent vortices give structure to turbulent fluids. I am inviting the critical eye to make a leap here and to see Darger’s paintings as representations of physical fields in which fluid dynamics are at play. By extension, I would suggest that Darger’s narratives (particularly My Life) are structured in a similar manner.

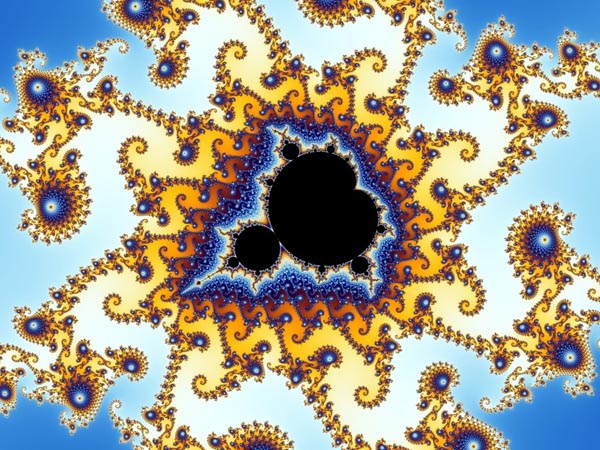

The narrative takes form via pockets (eddies, vortices) of order (story units) that arise and unravel in the onrushing flow of turbulent text. I call the text “turbulent” because it fails to conform to any sort of accepted narrative structural norms (story arc, climax, denouement, moral epiphany, reasonable length, etc.). Moreover, in the case of My Life, this integration of redundant orders reaches a complexity that begins to suggest fractal self-similarity, as the shape of the text, on various levels, repeats the shape of the storm it repeatedly describes; becoming what I call a vor/text. My Life may not make much sense as traditional storytelling or literature, but we can see Darger’s redundancy is actually a form of narrative structure, arising precisely because of the text’s inability to be confined by “literary” or “journalistic” constraints.

It remains to examine how the doodle can be read within this structural scheme. The redundant units in Darger’s writing (words, phrases, stories, images), inasmuch as they are verbal shapes, are emergent representations of the deeper organizational process, as the shape of this vor/text re-iterates itself on smaller scales, and one of these forms is Darger’s doodle. Thus what might seem a random occurrence is also a determined one, created by the pressure to organize meaning in the overlong hypergraphic narrative. Forms emerge and those forms become similar as they approach what we might call the narrative attractor of Darger’s creative impulse.

To put it another way: Darger sees a world in turbulence, a world constantly flowing toward disorder (war, social chaos, etc.) in which a semblance of order can be maintained or created by adding redundancy to the forward flow of textual events. These redundant elements are those that have the highest emotional valence for Darger—storm, explosion, flower, etc. Thus Darger’s doodles may expose in visual form the underlying organizational processes of the text, as if the text were looking for, or churning out a visual representation of itself from beneath the surface. This context allows us to view the totality of Darger’s output as operating on a whole other plane than that of personal symbolism (though it is that too), and see it as a representation of primal creational forces arising from turbulence.

Despite our human attempts to stabilize and read the universe as we see it, it remains essentially fluid, dynamic and turbulent. Art is one way we stabilize reality. Non-linear sciences have a role to play in both the production and interpretation of art. Pattern-reading and pattern-making are intrinsic to the production of meaning. They are essential to memory and early poetry, but also to longer narrative forms such as the short story and novel. We all notice that many writers write the same thing over and over again with slight variation. Some are unaware that they do this; others do so intentionally. The Austrian author Thomas Bernhard is a good example of the conscious use of circling narrative units as a way of organizing a story. Music is obviously aesthetically dependent on the repetition of motifs and choruses, from pop music refrains to Wagnerian chromaticism. And of course, we need only look to such “minimalist” composers as Steve Reich or Philip Glass to see modern examples of redundancy used as aesthetic strategy. Computers have made it possible to exploit the self-similarity giving rise to fractal design artists. Henry Darger’s visual and written works give us another window into this form of analysis and creation.

Example of fractal art: the Mandelbrot Set generating infinite self-similar versions of itself

Example of fractal art: the Mandelbrot Set generating infinite self-similar versions of itself

Image courtesy of MisterX.ca