Durga Puja 2023, Kolkata, India

Colette Copeland

December 2023

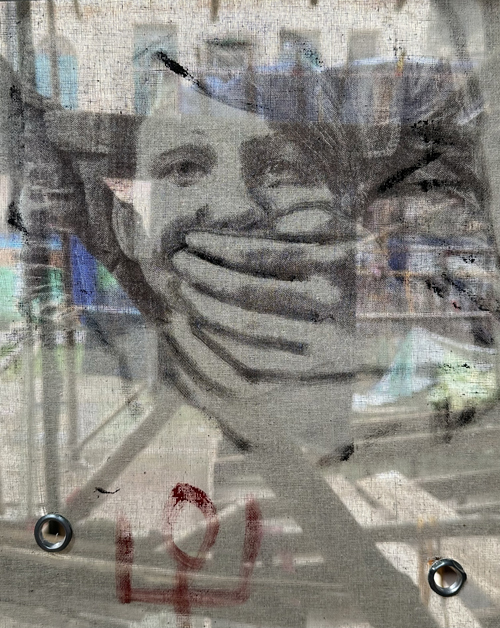

Bhabatosh Sutar, Divinity of the People, 2023

Bhabatosh Sutar, Divinity of the People, 2023

I was fortunate enough to time my 1st Fulbright India trip to coincide with Durga Puja, arguably the largest public art festival in the world. Surprising that it isn’t well known outside of India, despite its long history. The first Durga Puja mentioned in recorded history dates from 1606 and in Kolkata from 1610. For those who are interested in the history of Durga Puja, I recommend the short article linked at the end. Although the festival began as a religious celebration of the Goddess Ma Durga, it has become a celebration of community, art and culture. Durga Puja is now recognized by UNESCO as a world intangible heritage event. The intangible wording initially confused me, but since the festival is a yearly short-term event, rather than a permanent exhibit/structure, it garnered the intangible status. I would be remiss if I didn’t mention the outstanding work of scholar, historian and author Dr. Tapati Guha-Thakurta, whose research led to the UNESCO designation.

There are over 5000 Durga Puja pandals (installations) in Kolkata alone, as well as many in the rural areas and throughout West Bengal. My visits focused on the pandals selected by massArt India who organized the preview events for 20+ large scale pandal art installations. The story of Durga in Hindu mythology is complicated and I will not attempt to describe it in detail. After reading multiple accounts, my take is that Durga was a badass female goddess who rid the world of evil (in the form of demons), thus responsible for good triumphing over evil.

Pradip Das, Stories of Unseen Rebels, 2023, image courtesy of the artist

Pradip Das, Stories of Unseen Rebels, 2023, image courtesy of the artist

It is important to understand her badassery, since many of my favorite pandals explored themes of social injustices. I learned that there is contradictory mythology surrounding Ma Durga. Some view her as a symbol of female empowerment, a modern day superhero. This aligns with my interpretation. Another interpretation says that she was created by male gods and when she became too powerful, she was domesticated. As a feminist, that is not my favorite interpretation, but one that aligns with many world religions’ views of women.

As a Durga Puja newbie, my experience was one of magic and awestruck wonder. I felt like I was on a treasure hunt. Each work had the common denominator of a Durga alter, but there the similarities ended. Each installation presented a multimedia event—one filled with visual spectacle of lights, music and sometimes performance, but also revealing subtle nuances of complex narratives that intertwined Hindu mythology with contemporary culture and social issues. In this way, Durga becomes relatable (to me as a Westerner) not only as a goddess, but as a champion for human rights in today’s culture.

Rather than a central site, each pandal is located in a neighborhood and is organized and sponsored by a club. The term community is bantered about a lot in contemporary art, especially art that is deemed “social practice.” I witnessed communities coming together to create the pandals. It is not just about financing, although it takes a lot of money and support to realize these large-scale installations. It is about each member of the community taking a part in the production, whether it is the physical labor, making food for workers, or providing their homes as respite from the work. There is a sense of community pride, despite differences in caste, class and religion. One phrase I heard over and over again throughout my visit is that all are welcome here.

Rather than attempting an exhaustive summary of all the pandals, I will focus on a few that spoke to my interests in socially engaged practices. I had the pleasure to visit some of the pandals the week before the preview events, so was able to witness the extraordinary amount of work that goes into conceiving and producing these large-scale installations. Months and months of labor for 2 weeks of viewing.

Bhabatosh Sutar, Divinity of the People, 2023

Bhabatosh Sutar, Divinity of the People, 2023

Artist Bhabatosh Sutar from the Chander Haat Artist Collective created two pandals this year. He is an acclaimed Durga Puja artist who has worked with many of the same artisans and laborers over the past 20+ years. I had the pleasure of speaking with him onsite at Arjunpur Amra Sabai Club’s installation entitled, Divinity of the People. The first thing I noticed was his unusual depiction of Durga. She stands tall and proud–a fierce tribal warrior holding a spear. Her children are not portrayed as gods/goddesses, but as human children, gazing up in wonder at their mother. When I spoke to Sutar about his greatest challenge this year, he responded that he was concerned that people would misunderstand his nontraditional representation of Durga. I responded that his depiction symbolized the divine in all of us.

Ma Durga is shouting a call for action. But not a battle cry of war—one of freedom. Freedom from violence and freedom from oppression. During the pandal’s construction, news of the Manipur genocide began to surface. The violence started due to an affirmative action measure between two warring communities—the Hindu Meitei and the Christian Kuki. With hundreds dead and thousands displaced, the world stayed silent.

Durga is typically sculpted with 10 arms. Sutar’s Durga has two arms, again representing humanity. Her other 8 clay arms reach towards the sky. Severed from her body, I originally interpreted these as imprisoned or dead victims from Manipur. But upon looking closer, I noticed that their wrists were not bound with rope, as I initially thought, but covered in bangles. The gesture is one of solidarity and hope.

Since the pandals are located in neighborhoods, it is often difficult if not impossible to find bathrooms. Focusing on community, the crew at Arjunpur Amra Sabai Club built beautiful, clean restroom facilities with diaper changing stations, breastfeeding rooms, menstrual products and wheel-chair friendly access. This shows radical dedication towards inclusivity and hospitality for all. Durga would be proud.

Rintu Das, Don’t Want to be Uma, 2023

Rintu Das, Don’t Want to be Uma, 2023

Artist Pradip Das, who is also part of the Chander Haat Collective conceived and produced two pandals. Stories of Unseen Rebels located at Dum Dum Tarun Dal pays tribute to female freedom fighters who did not make it into the history books. I was surprised to learn that there was an all-woman unit called “Jhansir Rani” who left their homes, received military training and took up arms to support India against British colonialization.

Das’ sculptural installation beautifully interweaves history with personal stories. The structure includes light boxes with photos of the women revolutionaries, adding faces to the historical text. A cut-out sculptural figure of a sari-clad woman holding a rifle pointing towards the ground/audience, as well as the opened books in the Durga alter that reveal shapes of guns are startling reminders of the courage required to put aside gendered and cultural norms to fight for the country’s freedom, despite the risks.

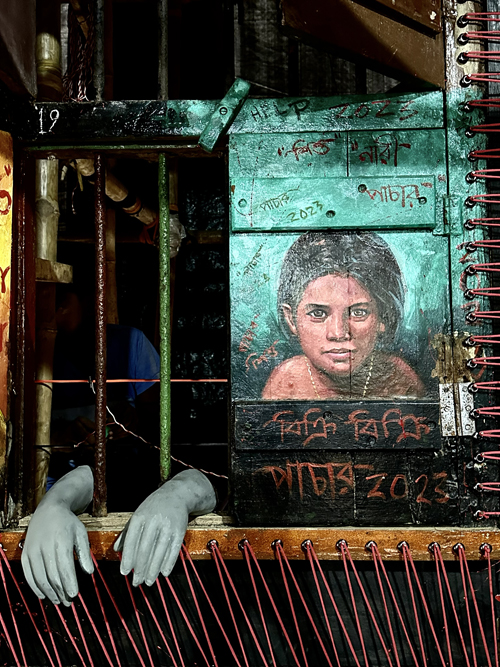

Pradip Das, Heartland: Montage of Memories, 2023

Pradip Das, Heartland: Montage of Memories, 2023

In Das’ pandal, Heartland: Montage of Memories, located at the Naktala Udayan Sangha club, he again reveals hidden histories. The work explores the lives of the residents of Naktala, which was the first refugee colony to be recognized by the government after Partition in 1949. Das collaborated with residents of the neighborhood over the past few years, interviewing them about their experiences with forced migration from East to West Bengal and their struggles to form new communities and identities.

The architectural structure made from salvaged materials referenced make-shift communities, providing a stark contrast to the personal objects—artifacts, photographs and paintings of families. One of my favorite aspects was the salvaged wardrobes that revealed family images distressed by time, symbolizing resilience.

Of all the pandals I visited, this one resonated with community and collaboration the most, since residents shared their memories, stories, letters, archives and cherished objects for the project.

Rintu Das, 2023

Rintu Das, 2023

Like Bhabatosh Sutar and Pradip Das, artist Rintu Das also created two pandals. The Barisha Club pandal explores themes of creation and destruction. The brick façade featured a goddess’ head with a missile protruding from her forehead. A flock of white doves circled her head like a halo. Sadly, I was unable to meet the artist, but it is a provocative statement to insert a weapon of mass destruction through a religious icon. Juxtaposed against the recent senseless tragedy and loss of life in the Gaza Strip, Das’ work points to the perpetual violence in the name of religion, hatred and power. Yet his work provides glimmers of hope and redemption.

The work that spoke most deeply to my heart was Rintu Das’ pandal about sex trafficking of children and women. I volunteered for 10 years for an anti-trafficking organization in Dallas, Texas that works with children who have been sex trafficked. This is an issue that I care deeply about and was happy to see a male artist take on this important topic. Located near the red-light district in Kolkata at the Kashi Bose Lane club, the multi-room installation contained different stages of trafficking starting with an auction table, to a room filled with small cages and finally a room filled with children’s faces. In many instances, perpetrators’ hands covered the children’s mouths to silence their screams.

Rintu Das, Don’t Want to be Uma, 2023

Rintu Das, Don’t Want to be Uma, 2023

I toured this pandal multiple times. During one of my visits, a young female tour guide said that this issue was an affront to Durga. Committing atrocities against women and children is akin to committing them again Durga, the divine goddess. It is not an easy installation to walk through. It forces visitors to confront their own views and actions. Like many countries including the U.S., buyers in India are predominantly men—men with money and power. The only way to break the chain of bondage is to stop the demand. Das’ work challenges us to not look away, but to be the voice of change.

Pradip Das, Heartland: Montage of Memories, 2023

Pradip Das, Heartland: Montage of Memories, 2023

All images courtesy of Colette Copeland unless otherwise noted.

Suggested articles:

History Of Durga Puja In Bengal →

Kolkata and Partition: Between Remembering and Forgetting →

The Manipur Crisis: Four Months of Unending Violence →

This is the eighth in a series of articles Colette Copeland will be doing as part of her Fulbright Research Award to India. Her research focuses on socially engaged artists whose work explores themes of borders and boundaries.

Interview with Moutushi Chakraborty →

Interview with Riti Sengupta →

Interview with Jyotsna Siddharth →

Interview with Mallika Das Sutar →

◊

Colette Copeland is an interdisciplinary visual artist, arts educator, social activist and cultural critic/writer whose work examines issues surrounding gender, death and contemporary culture. Sourcing personal narratives and popular media, she utilizes video, photography, performance and sculptural installation to question societal roles and the pervasive influence of media, and technology on our communal enculturation.