Diane Durant’s “Stories 1986-88”

Colette Copeland

August 2020

I’ve known Dr. Diane Durant and followed her work for the past 8 years. She is best known for her documentary and text-based photographic series. Although her work is very smart like the artist herself, it is never pretentious or inaccessible. She describes herself as a naked truth story teller. (Disclaimer–I added the naked part. She probably wouldn’t say that about herself, but I’m fairly confident she would appreciate the word play). I wrote about her 2018 exhibit Mental Pictures in which she questioned history and truth with sly nods to theorists Derrida, Saussure and Sontag. In this series, the text-only photographs are printed in the darkroom, allowing viewers to create their own mental imagery. Spare and lush, her prose reflects southern childhood experiences of wonder tinged with disappointment–the power of words to inspire and destroy.

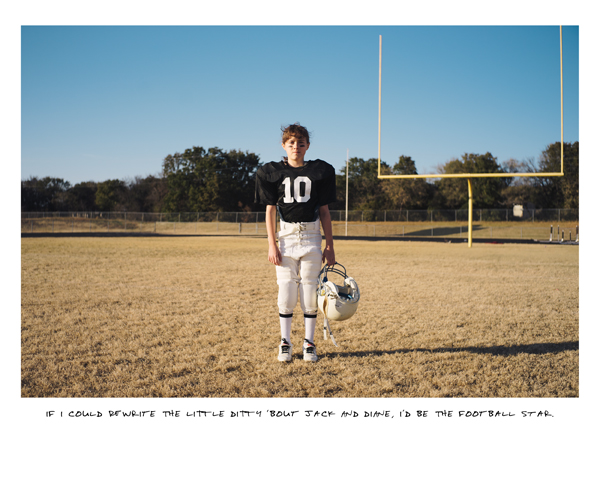

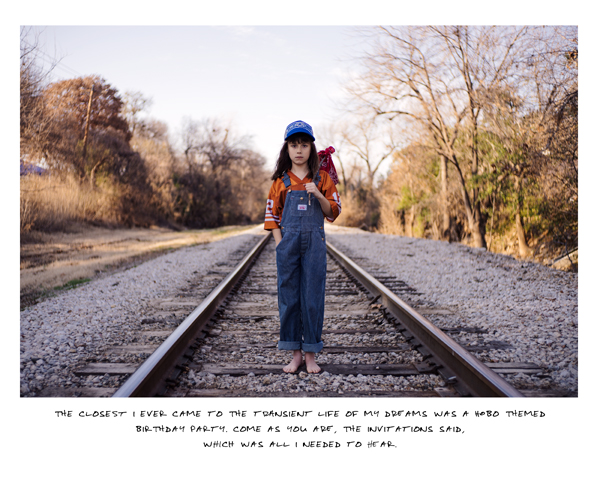

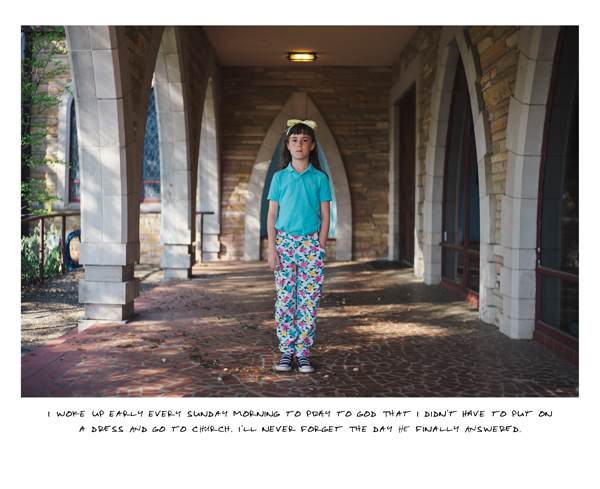

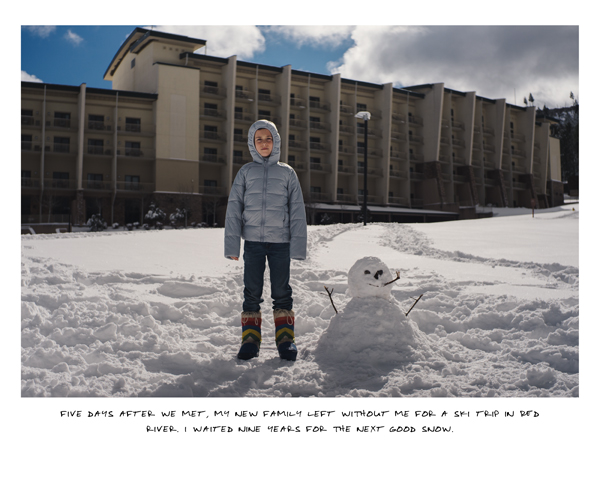

In her recent work Stories, 1986-88 published by Daylight Books in April, she continues the theme of revisiting childhood experiences; yet in this work, the image is dominant and with a new twist. Her 11-year old daughter Andie plays the artist’s childhood self, as they meticulously recreate formative experiences. Durant writes Stories is a photographic reconciliation of all the things I couldn’t change with all the things that never were, with a dash of adult-level cynicism and a handful of childlike innocence.

I had the pleasure of interviewing both Diane and her daughter Andie (who wrote the afterward published in the book). Andie is a 6th grader studying visual and performing arts at the Fort Worth Academy of Fine Arts.

CC: Andie–I’ve seen bits and pieces of the book as your mom was shooting it. It is so cool to see it finished. The afterward that you wrote is smart and insightful. As I am looking at all the images, I notice the consistency of your body language and facial expressions. It looks deceivingly like a family snapshot with you looking directly at the camera in the center of the frame, yet you are never smiling. Can you talk about the performative aspect or acting part of the shoots? How much of the story did you know beforehand and how did you mentally prepare to become this character that is your mom as a child?

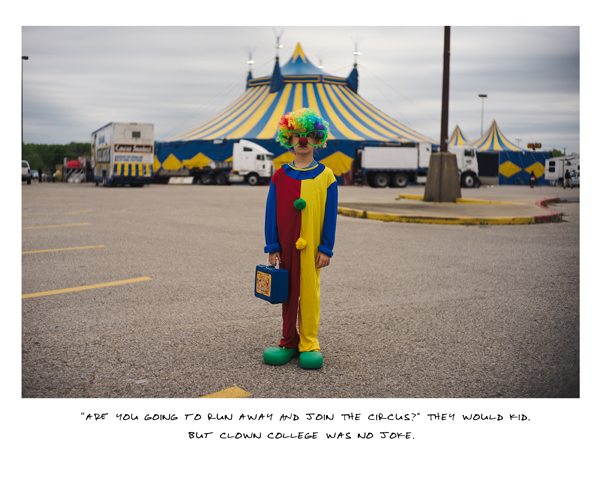

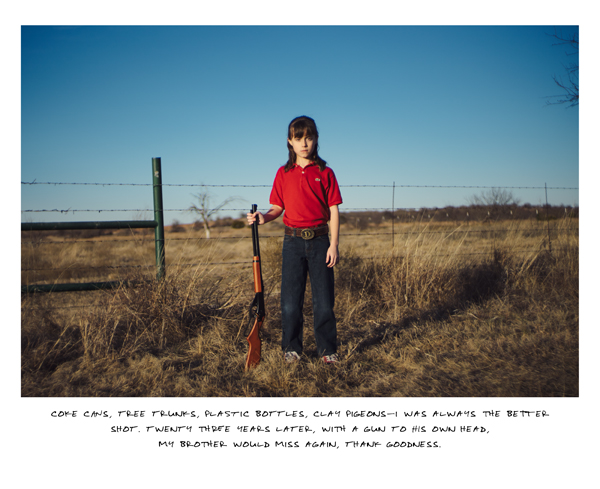

Andie: It actually felt kind of weird to be my mom when she was a kid. Even though we looked almost the same, we were so different. She wanted to do more “boy” things, like play football, and I like more “girl” things like dresses…I want to play with glitter…She wanted to play in the mud. The reason why I wasn’t smiling in the photos was because—as my mom has said—I stopped smiling in pictures when I was about three years old, but I don’t remember why. She thinks I was showing my “independence” (eye roll). So that’s what our family pictures look like, and that’s just how we did the project, straight-faced. I didn’t know a lot of the stories beforehand, even though I thought I did. For example, the shoot with me holding the gun. I thought that it was just my mom/me holding a gun about to go hunting, but it wasn’t that. Then talking about the whole story later just made us both sad. But to be honest, in some of the shoots, it was hard not to smile! I had to prepare myself to be serious, especially the circus clown one, because it felt more natural, more like me, and I wanted to be all goofy in those huge plastic shoes. I would say I felt like I was acting more as my mom in the Michael Jackson shoot, because I would not stand on a table and dance to Thriller like she did when she was my age, even though I do love his music. During the shoot I just kept thinking, this is so my mom.

CC: Andie–Once you read the text below the photograph, how did that change the meaning of the image for you?

Andie: As I said before, when I read the text on the gun one it made me wonder why? I just thought they were going hunting for the first time. It made me kind of sad to know that my uncle tried to kill himself. But he didn’t, which I am so grateful for!

CC: Diane–The work is really powerful. I have been thinking a lot about the notion of truth vs perception, and how our memory and experiences frame our perspectives not only on history, but current events. In your artist statement, you write about continuously becoming and unbecoming and how those moments have shaped your fictions and your truths. Please expand upon those ideas in your work.

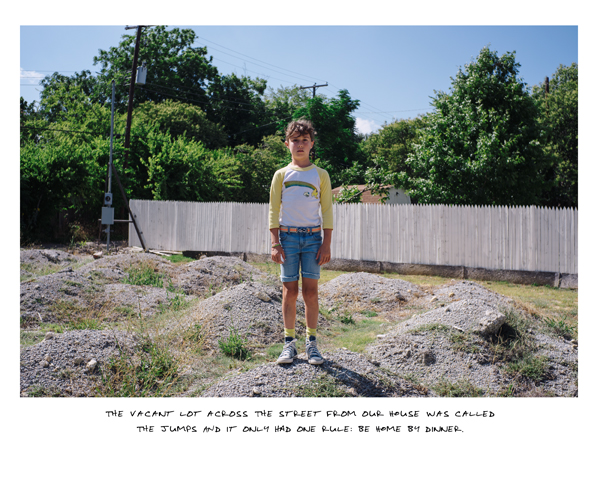

DD: Thank you! I really had no idea how powerful my memories were—the accurate ones and my interpretations of maybe the not-so-accurate ones—and how my recollections affect me. How I live, how I act, how I relate to others, how I parent. But by allowing myself to go through the therapeutic, and sometimes painful, process of realization, to both become and unbecome, I have been able to open myself up to what feels like a more reliable truth. Sure, my mythologies are a part of me, but I can relegate those to the realm of fictions now, which is where they belong. In the book, I get to group all of the narratives together, which gives equal authority to them, sure, but also gives me a point of reference for this time in my life, 1986-88, which has functioned as a repository for all of my negative impressions. I learned, through this project, that I didn’t only hold negative memories, which I wasn’t expecting when I started. For example, a piece about hiding in the holly bushes outside my bedroom window when there was chaos inside the house turned into the memory of taking our bikes to “The Jumps,” a vacant lot in the neighborhood, and riding until dark with only one rule: be home by dinner. That was a freedom we had in the 80’s that doesn’t really exist today, and it’s certainly not one that I would impart to my daughter. But other images have a strength, an audacity, in them, and that is something that I do want to pass along to her.

CC: Diane–I notice that some of the images refer to a very specific memory like the one about your brother’s attempted suicide or the hobo-inspired birthday party and some refer to the generalized time period 1986-1988 like the church or holly bushes images. How did you navigate between the general and specific when selecting memories to recreate?

DD: Initially, all of the images felt specific. I am a child of the 80’s, born and raised in Texas, with all of the usual clichés that come along with it. And I was tomboy, trying to navigate what that label meant to me as well as what it meant to my parents, who didn’t have the “pretty in pink” daughter it felt like they wanted or could understand. But as I began to share the early images, the feedback I got was unexpected: these stories were universal. If you lived in small-town Texas or the south, you could relate. If you were a kid in the 80’s, you could relate. If you were gender non-conforming, you could relate. And that encouraged me to keep telling my stories, knowing that they weren’t just mine. I felt like I had a responsibility to tell the truths of my generation, of kids like me, who were apparently greater in number than I realized, then or now. Of course, some of the images have multiple motives. I wanted to show who I was as a kid—a kid who had a hobo-themed birthday party and routinely dreamt the romantic dream of running away to join the circus—and what my family was like, which was fraught with the chaos of alcoholism and the concern of what others will think. My brother and I both bore the weight of that reality, but we dealt with it quite differently. I was the clown and the overachiever, and he was the scapegoat. And it’s still that way today, which is why some of the images do introduce aspects of a more recent understanding of our present lives and how that rubs against what I remember about us from the past. There is a sadness that weaves itself throughout the book, but ultimately, that sadness doesn’t prevail.

CC: Diane–What is the significance of the text-only pages to the narrative? Why did you decide to omit the image on those pages?

DD: It wasn’t so much an omission as a bolstering of the representational power of the text itself. I wanted the images and the text to be co-equal in their telling of my stories, rather than the text functioning as a caption subservient to the photograph. But since I decided to place the text below the image in the pairings, I knew that the reader-viewer’s natural inclination would be to give the photograph more weight. The text, when by itself, also functions as an image, allowing the viewer to make their own mental picture, which also has an authority in the book since, like I said before, these aren’t just my stories. I wanted to establish that shared experience and authorial voice, even if I am the formal narrator.

CC: Diane & Andie–What was the best part of this project for you? The worst part?

DD: The best part, inarguably, was working on this project with Andie. Although she didn’t have total control, she did have a say in how some of the images were executed and when. She didn’t get to grow her bangs out for three years, and she didn’t get to wear better-fitting clothes (in her opinion), but she did get to interpret my retellings into a character that she was comfortable with playing (hence, the deadpan stare). And watching her take this on, take on the person of me and become the me that I couldn’t be, was both moving and entertaining. And now we have a book to show for it, that she can show her kids one day when they ask what she was doing at their age. If she has kids. She can be whoever she wants to be! (And this is how this project changed me as a parent…) As for a worst part, it would probably be how frantic some of the shoots were, because of the weather or the sunlight or the driving to New Mexico just to find snow for February 1988, which was the only good snow any of us had for a decade. She would probably say it was when I burned her forehead with the curling iron, but I still maintain that it was my mom’s fault for perming my bangs at all.

Andie: My favorite part was probably doing the funnier shoots—or dressing in the funnier outfits, like the clown ones—and definitely getting to bond more with my mom, spend more time with her, and learn more about her life. The worst part was definitely my mom BURNING MY FOREHEAD…THREE TIMES. THREE!

CC: Andie–After doing this project and learning about your mom’s childhood life, if you could go back in time and meet your mom at age 10, what advice would you give her?

Andie: If I could go back in time and meet my mom I would say “Do NOT let your mom perm your bangs!” Because it hurt. Three times. And also, don’t let anyone stop you from what you want to do.

dianedurant.com →

www.instagram.com/betweenhereandcool →

Diane Durant’s book “Stories” is available at →

◊

Colette Copeland is a multimedia visual artist/writer whose work examines gender, death and contemporary culture. Sourcing personal narratives and popular media, she uses video, performance and installation to question societal roles and media’s influence on enculturation. Her experimental videos employ absurdist humor to explore the landscape of human relationships. She proudly admits to providing her children with years of “therapy” fodder.