Dale Tracy, Gnomics: Review

Daniel Barbiero

July 2024

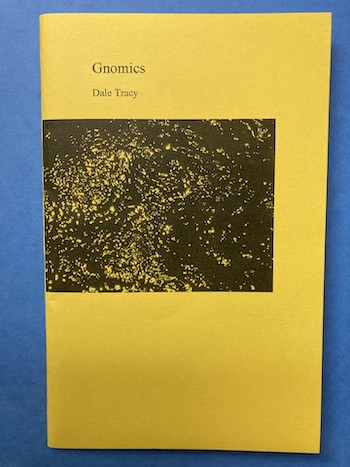

Dale Tracy, Gnomics

above/ground press, 2024

“Gnomics” is the name that poet Dale Tracy has given to the twenty-four short poems that make up the content of her new chapbook of that title.

A gnomic utterance is a short, condensed statement of a universal principle or observation, often couched in enigmatic or figurative language that gives it the appearance of profundity. Think, for example, of the aphorisms that earned Heraclitus the nickname “the obscure”: “a hidden harmony is better than an obvious one”; “the nature of things likes to hide”; “changing, it remains the same.” These are pithy statements that purport to speak of universal truths, but do so mysteriously enough that even after twenty-five hundred years there’s no agreement on what Heraclitus really meant.

Tracy’s gnomics don’t share Heraclitus’ willful obscurity, nor do they claim to present universal truths. For Tracy, “a poem is a model for doing rather than an explanation of something” – a way of learning about the world rather than pronouncing on it. Hence her gnomics present her in the process of thinking through the world and doing so in as condensed a manner as possible. They are, in effect, discrete objects in which a thought is totalized in a tightly-bound linguistic enclosure.

Take, for example, “Ars Poetica,” the collection’s opening poem:

You must eat your midnight and roses

or there’ll be no pounder of spices.

This single sentence poem mimics a conditional statement of the “without X there can be no Y” type, recast as a chain of associations. How these associations come into contact with each other is an enigma for the reader to interpret. “Eat” and “spices” may be connected through the implicit but absent intermediary term of “food” (spices make the food we eat palatable); “midnight” and “roses” associate with each other as cliched tropes of sentimental poetry. Are we to “eat” them figuratively, make them and their bland like disappear, in order for real poetry, its more challenging or substantive tropes akin to the spices that give food its pungency and which must be pounded out by the poet, to emerge in their place? Possibly, and a possibility latent in the title. “Ars Poetica” may be totalized syntactically – rendered a complete thought in which each association has its proper place in a sequence of associations – by its logical structure, but its meaning is not. It’s poetry, and not to be exhausted in a single reading. Its meaning resides in the ambiguity of its images rather than in its logical form.

The tension between logical form and poetic content is something Tracy plays with throughout Gnomics. “Logic 3,” one of five poems title “Logic” which play with syllogistic forms for poetic effect, reads:

What can be created can be destroyed.

Knowledge can be created.

Some knowledge nourishes dirt.

The first two sentences give us the premises, which don’t lead to the conclusion we’d expect, which should be “Knowledge can be destroyed.” But this is a poem rather than a syllogism proper, so we have to derive the conclusion analogically rather than logically. Organic matter nourishes the soil as it decomposes (is “destroyed”); transferred by analogy from organic matter to knowledge, the image of decomposition represents the more general idea of destruction which we now can see applies to knowledge, though apparently not to all knowledge.

Modeling the progress of a thought in language – seeing it through from its beginnings in a string of words in search of a meaning to its totalization in a completed unit of signification – is one of the aims of these poems. Tracy has described them as “open[ing] up a line of thought” through which “the thinking emerges from the poem as a process.” As we’ve seen in “Logic 3” that process can consist of drawing conclusions by analogy; we can see another kind of thought process in “Pocket Sky”:

A jagged tree is a key to the sky,

which turns around it slowly.

The thought modeled here mimics the apparent turning motion of the sky: it spirals outward from a central kernel consisting of a single image – a tree whose ramified branches resemble the teeth and notches along the blade of a key, as it protrudes upward in a clearing – and expands into a complex metaphor that reverses our expectations through an incongruity in the way it’s elaborated. A key is something that works by turning within a space, but here it’s the space surrounding the (metaphorical) key that turns; this reversal of the conventional order of things heightens our awareness of the way the metaphor is constructed – we follow the path the thought takes as it rounds a curve we didn’t see coming. If the tree is a key the sky is the cylinder containing it; what’s more, the tree provides a key to our noticing the sky by virtue of its vertical orientation directing our gaze upward. The image of the tree has the added effect of setting up an implicit pun with the title of Tracy’s collection: it “rhymes” with the image of the gnomon, the vertical rod ancient geometers used to measure the length of shadows.

The extended metaphor in “Pocket Sky” works by combining the two more-or-less distant elements of the tree and the key. They combine partly on the basis of a symmetry of physical resemblance and partly on the basis of the similar sound profiles of “tree” and “key”: both are monosyllabic words beginning abruptly with hard consonants and ending with the same long vowel sound. It is a method of forming associations that recalls Surrealist poetics.

We can see this again in the riddle-like “Fallacy”:

A mind like saloon doors:

all spur, no horse ride.

We can imagine a mind being like saloon doors – loosely hinged and swinging open and shut with every random stranger passing through – but the linkage from that opening simile to the implicit image of a horse being prodded with a spur but refusing to move requires an alogical, imaginative leap that on the surface produces a mixed metaphor. But it’s a leap clearly meant to elaborate the simile in a different figurative register since, like the stubborn horse resisting a prod, such a porous mind would most likely be one that doesn’t move itself to think, despite getting a push. Rather than a mixed metaphor, we have a complex and wryly humorous surreal metaphor-by-association. It really isn’t surprising, then, to see Tracy, in an interview last year, describing her way of thinking as having a “surreal bent.” With Gnomics, she makes that thinking the meaning, rather than just the means, of the poetry.

Gnomics is Tracy’s second book with above/ground press, following 2020’s The Mystery of Ornament. The Ottawa-based press, which is curated by publisher rob mclennan, specializes in elegantly presented poetry chapbooks like Gnomics. It has published more than 1325 titles so far and celebrates its thirty-first anniversary this month.

Dale Tracy, Gnomics, above/ground press →

Daniel Barbiero is a double bassist, composer and writer in the Washington DC area. He writes on the art, music and literature of the classic avant-gardes of the 20th century and on contemporary work, and is the author of the essay collection As Within, So Without (Arteidolia Press, 2021).