Courses @ The Block Gallery

Ron Morosan

September 2019

Images courtesy of Argenis Apolinario

Images courtesy of Argenis Apolinario

In the 1987 film Babette’s Feast we are given a tale set in 1870’s Denmark in which an acclaimed Parisian lady chef is employed as a lowly cook by two elderly spinsters who have no idea of her past. However, after winning a large sum of money the cook decides to create an expensive dinner and reveal her tremendous talent for cooking a superb meal that is like a symphony of culinary delights. Inviting the local citizens to participate, the dinner is a tremendous production of gastronomical art and a huge success for the chef.

Going out to dinner is now a universal convention in western cultures, with the ritual of selecting a restaurant, arriving, being seated, selecting from the menu, and being served in a courteous and efficient manner. But if we look at this convention in a conceptual way, say as social anthropology, what really is dining out? What does this ritual say about ourselves and our culture?

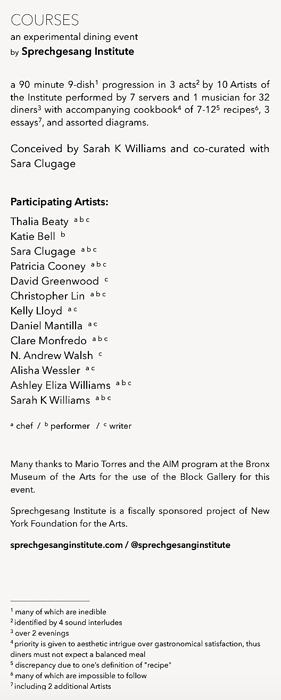

I was invited by Sarah Williams to a dinner at the Block Gallery at 80 White Street, generated by the Sprechgesang Institute. The Block Gallery is the newly opened location of the AIM initiative of the Bronx Museum, a residency program and project space initiated and named after Holly Block, the former director of the Bronx Museum.

Arriving at 7:00 pm, I was one of sixteen people who would have dinner at a long table covered in a white tablecloth. I soon noticed that there would be an audience of about a dozen people who would watch us dine. As I took a seat I noticed a strange cloth napkin with two holes in it, which I somehow tried to figure out how to use. The woman next to me had an enormous napkin that looked more like an apron. I thought, this is going to get very creative.

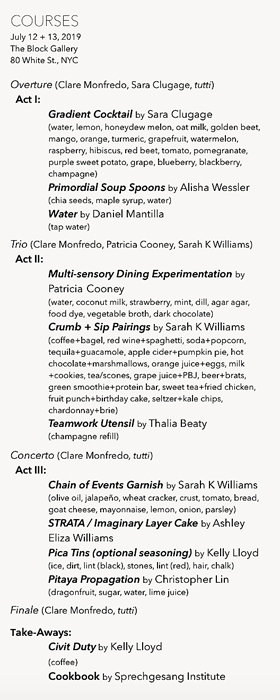

A menu was neatly tucked into a pocket to my right, and as I read the program I realized this dinner was more a theatre or performance piece, with three acts, with accompanying live music, and courses that had names like Gradient Cocktail, Crumb + Sip Paintings, Chain of Events Garnish, and STRATA/ Imaginary Layer Cake, with each course designed and prepared by different chef/artists.

I am not going to describe every dish of this very complex performance/ dinner, but some of the highlights really surprised me and made me think about what constitutes dining. In Act I, we were served a Gradient Cocktail of champagne poured over huge ice cubes made of different fruit juices. (This was a good start to loosen us up for what was to come. Needless to say, it was delicious.) Then Primordial Soup Spoons were passed around that could be good examples of what Magdalenian Homo sapiens might have devised. With these we tried to eat a chia maple soup that was not memorable.

In Act II the Multi-Sensory Dining Experiment was served; each diner was given a tray of sorts with little fingertip food shapes, and a vegetable-like substance, accompanied by a soup-like material and with tweezers provided as utensils we were invited to eat. This challenged my sense of dining adventure, so I more or less just picked. (I noticed that the woman across from me ate everything. She said she was hungry.)

In Act III Chain of Events Garnish consisted of a wafer-like sandwich, a cracker that was smashed by our server, and a kind of weird salad. I ate the entire wafer sandwich and it was tasty.

Each act was accompanied by a cello player whose sounds wove in and out of other sounds, some consisting of voices talking on a radio, and then sounds that resembled noise in a busy kitchen.

Near the conclusion of the dinner I started thinking: Is this what John Cage would have done if he opened a restaurant? That would be close. There was a definite sense of avant-garde dining going on with a strong sense that diners really were experimenters. We were being asked to engage in questioning: What is dining? What is the ritual?

I invited Sarah Williams to answer a few questions about her goals and procedures in developing Courses with her compatriots.

How did you develop the idea for the Sprechgesang Institute?

I started developing S.I. in Berlin in 2016. I was living there on a Fulbright studying opera and surrounded by so many intensely fascinating and brilliant researchers, most of whom were not artists. After so many years isolated in a visual arts community—through grad school and my first few years in NYC—this academically diverse environment was incredibly exciting and refreshing! I put together the first iteration of S.I. there, to work on a small collaborative performance project. Fortunately many of the original group eventually ended up in NYC and make up the foundation of the S.I.

Conceptually, I knew I wanted the freedom to take on new structures of relatively unfamiliar genres of work with each project, giving us permission to leap from one discipline to the next without hesitation. I am interested in collaborating with people who work across disciplines and are genuinely curious in a range of areas. Because of the many structures we take on, I knew an over-arching aesthetic was important for continuity. This was there from the beginning: institutional elements—staples, file folders, clip boards, a precision in execution, an overly-complicated and formal language, a particular absurdity and humor, color palettes, uniforms, gestures, footnotes. In short, it’s really all about the footnotes. The dining utensils and serving equipment were custom-made.

Was this done by all members of the Institute or by a couple of individuals?

For the most part, each individual artist was responsible for all aspects of his/her dish. I co-curated this event with Sara Clugage, so together we met with each artist to work on developing their dish. I encouraged the use of the particular serviceware, utensil, and vessel most conceptually appropriate for each dish. As a collaborative platform, we are able to reach out to each other for specific skills as needed, so this became helpful with this project, as many of the elements were fairly layered. Additionally, not all dishes were presented exclusively by their maker, so it was a matter of teaching each other how best to present our dishes.

The catalogue for Courses was very creative, and one of the most interesting articles by N. Andrew Walsh, PhD required a high-powered magnifying glass to read. A certain inaccessibility is presented there and is part of the dining experience.

How did you develop this kind of approach and what were you thinking about?

I don’t aim for inaccessibility but I am attracted to overly or needlessly complicated structures, and there is certainly a relationship between these things. As far as the catalogue/cookbook goes, the size of the text was initially just a practical decision—in wanting to be able to include as much writing as possible in an affordable format, but often, in the Institute, even the simplest of tasks (like reading) require additional steps (like a magnifying glass) to achieve. I think that by disrupting the most logical path—through the inconvenience of footnotes, or the needlessly large napkin, etc—assumptions are broken down and surprise creeps in with the struggle for understanding. I like the absurdity of over- complexity, and I think, in general, I subscribe to a bit of a Rube Goldberg approach to most things. There was a theatrical element to the whole experience, which was affirmed by the dozen or so people who were sitting to the end of the table as an audience.

Were you referencing a “Living Theatre” concept?

The audience, to me, were the 16 diners, and the people seated on chairs around the table were the 6 observers. These chairs were added later in order to include as many people as were interested in attending—we didn’t feel comfortable turning anyone away. Ideally, the table would be long enough to accommodate everyone, but, as the dishes are so involved, it became unreasonable to construct any more than 16 identical portions for any one course.

During the first performance, a few courteous audience members began a sort of rotation with the observers so that everyone could have a chance at being a diner. This rotation was unplanned, but I am grateful it happened, and I think it was consistent with the pacing of the evening. I’m 100% not concerned with any of S.I.’s events fitting neatly within any one genre, so that this piece existed somewhere between a dinner, a theater piece, a dance, or whatever else, is exactly as it should be. I’ve always resisted exclusively adhering to one particular discipline—as an artist, why limit yourself?? I want to keep S.I. as open and fluid and curious as possible.

COURSES

Sprechgesang Institute at the Block Gallery

80 White Street, NYC

◊

Ron Morosan is an artist, writer, and curator. He has shown his work internationally at the American Pavilion of The Venice Biennale and the Circulo De Bellas Artes in Madrid, Spain. In the US he has shown at the New Museum and had a one-person exhibition at the New Jersey State Museum, and at numerous galleries in New York. He curated the Robert Dowd exhibition, Subversive Pop, at Center Galleries in Detroit, as well as Denotation, Connotation, Implication at Eisner Gallery, City University of New York. He has written catalogues for many artists, including Enid Sanford, Tom Parish, Robert Dowd, and others. In the 1990’s he started and ran B4A Gallery in Soho, New York, writing press releases, articles, and catalogues.