A Conversation

With Chris Teerink

Having seen the press screening of the documentary film “SOL LEWITT”, Film Forum publicist, Adam Walker was good enough to arrange for me to have a meeting with the film’s director, Chris Teerink. He had just flown in from Amsterdam to meet with press. address audiences and take questions at the film’s opening. It is hard work to promote a film.

A week later I was fortunate to be the first to meet with him that morning. When we sat down with some coffee I immediately let him know how much I enjoyed his film and respect his craft. I found it easy to establish a dialogue with him. He is very intelligent and sensitive. He demonstrated a genuine connection to art. He has a feel for and knowledge of the personality and work of Sol LeWitt. Our recorded conversation went on for about a half an hour. What follows is an abridged transcription.

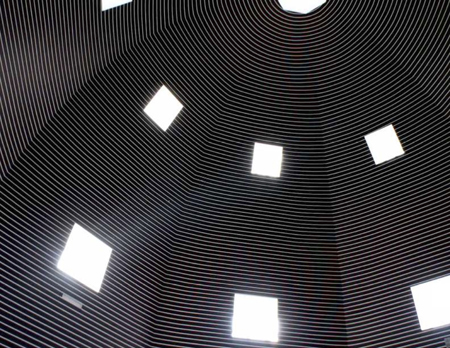

JO: I saw your film and I was completely delighted. Technically I think its beautiful, Visually pleasing. The camera work is gorgeous and the weaving in of the spiral drawing #801 into the film, letting us know there’s going to be this wonderful revelation at the end, the pulling of the tape. It comes as no surprise. You develop a tension and anticipation which I completely enjoy, that being said, I could go on heaping praise…But.

My first question is why did you choose Sol LeWitt as the subject of your work?

CT: That’s very simple. On March 1, 1984 I turned 18 and on that day the Dutch 8 o’clock news ran an item on the opening of a Sol LeWitt show in the Stedelijk Museum of Modern Art in Amsterdam. I was already involved with art, going to art school. I knew art history, but I had never encountered anything like that. So I saw it on TV and decided to go see the show. I was not living in Amsterdam at the time and it completely changed my whole way of thinking about art. That an idea can be art or the motor that produces art! I sensed the work that was behind it even though you couldn’t actually see it, but you felt all those lines. It stayed with me. And then I forgot all about it. I grew older doing my own thing. But, as a film maker I made things that start with an idea. Not so much a thing but an idea, a conceptual thing. In 2003, I think, together with my wife I made a film about Jonas Mekas and the Anthology Film Archives. That film was shown as part of an exhibition in the same museum where they made the spiral drawing and I really liked the idea to show a film in the context of a museum rather than in a cinema. We really liked it and we said to the museum people if there’s anything in the future that we can do together lets do it. That would be a good idea. Years later I was in NY with my wife staying with her parents for Christmas I got an email from someone at the museum saying they are going to redo the spiral wall drawing by Sol LeWitt. And by chance or not by chance my wife and son and I were going to DIA Beacon the next day where they have a beautiful collection of his drawings and I was standing there and I was 18 again and I decided this has to be a film.

JO: It was meant to be.

CT: Yeah, and the original idea was to make a film about his relationship to Holland because that was a very strong relationship right from the beginning. As I did more and more research that expanded and I decided Italy is very important in his life and his work so I thought we need to go to Italy. And then as I was doing my research there was the MASS MoCA show that is so great we have to include that and then there was the exhibition in City Hall Park, that too. Basically it goes back to March 1st 1984.

JO: So that’s the genesis.

CT: Yeah, and I looked at that news clip from the 8 o’clock news in the archive but decided not to use it. It would be very strange to make a movie about someone who does not want to be interviewed and put your own persona up front. It doesn’t make any sense.

JO: What you had to say about his mode of work when you first encountered it and were focusing on the conceptual aspect of that. I identify with that. I understand what you’re saying, correct me if I’m wrong, it is directly analogous to film making. These pieces have a life but they are in a certain sense disposable, temporary if you will. If you have a Rembrandt and it catches fire and its burned. It’s gone forever.

CT: Except in the memory of people.

JO: But, then those memories die too. But in the case of these LeWitt pieces they exist as concepts. Expressed only in the labor of others.

CT: 200 years from now you can make a Sol LeWitt and it will still be an original work. That’s amazing! That idea is mind blowing.

JO: And in the plastic arts, in sculpture and painting it is. It’s not amazing in musical composition… It is a shift and also a major shift in art as well.

CT: And it’s a major shift where it concerns economic aspects of works of art. That’s also what attracted me.

JO: I would like to hear more about that. I know a lot of people have ideas about that. What exactly are you saying?

CT: Well, we’re used to in visual art, that a painting has a value, probably the value gets bigger. Some paintings people pay millions for and the whole idea was to attack that by making works that are not unique. LeWitt made the “100 dollar” drawings, never to be sold for more than 100 dollars. Of course that doesn’t work in the world we live in. But I have a personal theory… maybe he solved that by giving away most of his work. I think that was his personal solution to the problem. Whoever you speak to that worked with him, they have original works of Sol. He’s not the only artist who does that of course.

JO: Well, he was modest, his ego seemed to be in the right place. He sold work enough to make a living but it wasn’t with the intent to commodify his work and I suspect by not having his hand on it takes away the commodification of it, in one sense. I suppose that one could argue that Jeff Koons doesn’t put his hands on his works but his works are indeed commodities.

CT: A lot of the 17th Century painters didn’t do everything themselves either. There’s nothing new it that. It’s their name underneath, their signature that gives it a certain value.

JO: In the case of LeWitt there was a purity of concept. The concept was primary. What comes to mind right now is back in 1966 in NY there was a show at the Jewish Museum called “Primary Structures” in which Lewitt showed his early work which he himself called structures.

CT: That was even before the show in the Hague.

JO: I paid a visit to MASS MoCA. I toured the retrospective, it was stunning.. You portray that beautifully in your film. Taking us visually through the exhibit, not showing us frame by frame by frame, wall drawing, wall drawing…It has a beautiful thread. There are too many pieces there to show in your film and I’m sure while editing you probably had a hell of time

CT: Well, it was not easy. One of the reasons I thought I could make this film was because if he was just a painter that makes paintings I would probably not have had the guts to make a feature length documentary about him. But because when you experience his work you perceive it in space but also in time. They’re too big to see in one moment, so you have to walk past it. That is of course, what cinema is about. And that’s why I thought, yes, it is possible to make a film that’s good, not like a slide show of paintings with people talking about them. I’m not interested in doing that to begin with. As a viewer you are actively involved with the film, you see how something is being created, that’s where it all starts, the cinematic aspect of space and time.

With my cameraman we started thinking okay, how are we going to do this, some traveling shots makes sense, but others with a very simple pan. So with every wall drawing we looked at we asked “what are we going to do with this one?” “How do we think we can film this in the best possible way?” and we were not limited by a certain fear of not representing the work in the right way. “We have to do it the way we see it and not worry if we don’t show the whole work.” By allowing ourselves that freedom, that’s the reason we touched upon an essence that people seem to respond to.

JO: Your choice of sound and music is a very good marriage with the imagery, not imposing.

CT: Rutger Zuydervelt is the composer. He’s a very young guy and I’ve been following him for a number of years and I thought this is the perfect film to work together on. We worked very close and the funny thing is that way before I started filming Rutger and I talked about my ideas about the film and we went through books to see some of the shows and all of a sudden he sent me an email and said “here’s a link to some musical sketches I made for the film“, way before I started filming. There were 24 sketches and I was blown away. That was exactly what I wanted. This guy really understands what I want with the film. He translates it into music. Then he was asked by a British musical label to put some of his work on vinyl 4 EPs and CDs, so before the film was even finished his music was released and had already 2 reviews in internet magazines. Ha, ha, ha! I used those sketches during the editing. Then we went back and forth. He changed the music and it really paid off.

JO: Well, what you’ve done is you’ve represented a point of view which is what anybody has when they walk thru a gallery space. You choose what you’re going to see and you choose the distance and you focus on whatever point of interest there is. It’s a personal view, but your choices are either make an archival document of the image or look at what you are really interested in visually. You certainly have made the right choices by doing that because otherwise what’s the difference between seeing the film or flipping through a catalogue?

CT: Exactly. That’s the aspect of time and that’s what cinema is all about.

good interview compelling revisitation of the art definitely would like to see the documentary.