A Collaborative Review

Nicole De Brabandere & Kathleen Reichelt

April 2020

Between Dialogue and The Image in “Imagine Van Gogh”

K: Vincent Van Gogh is one of the most well known artists of the twentieth century. His life story, made known through letters he wrote to his brother, has morphed into modern myth and now resides in our collective knowledge. Who doesn’t know the image of the red haired man with bandaged-severed-ear? Filmmakers and storytellers have been working with this tragic figure for decades, reshaping parts, reinventing endings. I’m one of the storytellers working on a version of his story, which is why I travelled to Montreal during the coldest week of January, to experience the Imagine Van Gogh exhibit at Arsenal Contemporary Art Gallery. The story Nicole and I walked into was presented by Paul Dupont-Hébert and Tandem, and designed by Annabelle Mauger, using the concept of “Image Totale”.

N: My interest in expanded cinema, and the aesthetic and relational potentials that can emerge through rethinking the relation between screen, image, light and audience meant that the role of the design of the exhibition itself, and the concept of “The Total Image” that it was based on, was as much part of the content of the exhibition as much any archival material from Van Gogh’s oeuvre. The projection technology adapted by Mauger and Baron constituted a compelling proposition for making a break in the fixed status of the art object though amplified some concerning aspects of the story of Van Gogh, and its assumptions about the autonomy of the artist, the historical referentiality of art and the freedom of the spectator.

N: Before entering, we both wondered where does such a story leave us, what impact can we possibly make as artists, interested in what the aesthetic can do to create the possibility for new forms of sense, articulation, care and collaboration? In what way can the work of someone like Van Gogh, with its signature vibrant colour, texture and dynamism, make a case for how the material process of painting itself can generate opening for thinking with relational and aesthetic possibilities beyond the fixed positions of art object, the artist, and the spectator? How does situating these painted textures within a large scale surround of projected images dampen or intensify such potentials? As old friends used to open and engaged discussions about art and philosophy, the way that our thoughts move and transform so quickly and easily in dialogue with each other, we begin with our own exchanges. We enter the exhibition, not as free and independent spectators, but as already bound to and emergent with the rhythm of our conversation, and dynamism with which we articulate the experience of the exhibition.

K: We walked into what could be called a kind of holding room where visitors could enter and read information about Van Gogh’s life and the exhibition from gently swaying panels hung from cables extending down from vast heights, their slight but continuous movements upsetting the domestic scale and aesthetics of the panels themselves. The story of Van Gogh’s life was mainly pieced together from letters between Van Gogh and his brother, and documents from his religious and military posts, a now familiar account save for a few new details. These details though, quickly faded against the monumental scale of the projections of his work and its monumental impact in constituting the Western artistic canon.

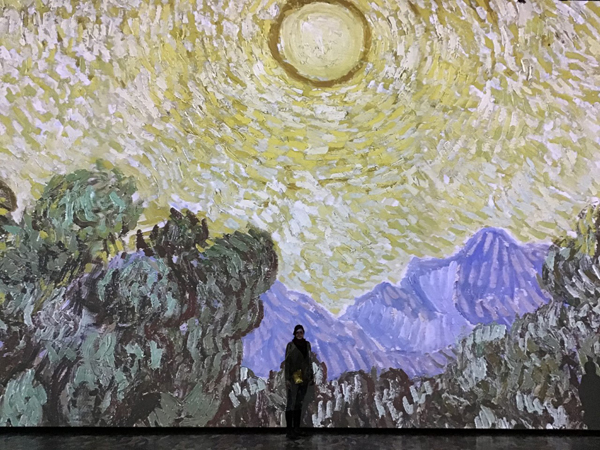

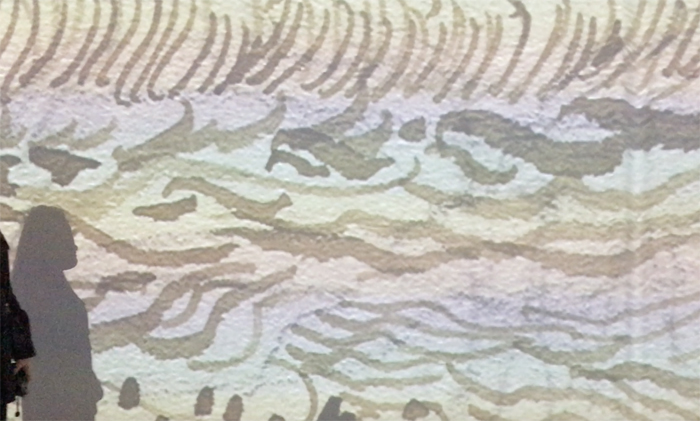

K: In the Imagine Van Gogh project “The Total Image” deploys projection technology to “map” and “narrate” the projected image. The exhibition program states: “The Image Totale’ of the Imagine Van Gogh project is appreciated as a whole, as it creates a continuity from a set of images that are linked together to form a specific type of narration”. We are left to question: how do we make sense of this narration? What exactly is being narrated and how do we understand images to narrate in this strange and yet familiar media scape? Our experience is a series of images projected on enormous screens, and the technology is impressive. Projections of Vincent’s paintings on 30 foot high walls portray half inch brush strokes as six feet long. The cracks in the paintings are revealed. Vincent’s landscape sketches become abstract markings. Every wall and even the floor is covered in a continuous loop of his works. Over 200 of them. Gently fading in and out, panning left and down, moving and shifting in a “powerpoint” meets cinematic gesture.

N: There are no gaps in the space of projection—the light covers the entire surface of walls and floors. I am immediately drawn to the edges of the huge screens, where they meet and gently undulate as people pass by on the other side of them, gently distorting the projected image. The difference between images also appears in the less subtle way that images are co-ordinated or orchestrated, sometimes playing the same movement, image or motif, and sometimes not. “The Total Image” claims a lineage with technologies of topoprojection developed by Albert Plécy’s Cathédrale d’Images that from 1977, which were developed for the specific surface of the quarries of Baux en Provence where they were projected. Mauger and Baron initially desired to project images of Van Gogh’s works on suspended curtains in a very long and narrow format corresponding to the Japanese ‘okio-e’, a style that was dear to Van Gogh. In Imagine Van Gogh, whatever specificity such surfaces may have imparted on the image and the experience of encountering the image is absent. In the Arsenal iteration, the automated movement of projected images (between pauses) imparts a continuity on the images that universalizes the spacetime of video playback, the passive ground and abstract materiality of the projection surface, and the Cathedral-like proportions of the space, one where the individual is supposed to encounter their contrast in the form of the infinite.

K: This is in keeping with what is suggested in the exhibition catalogue, that in “The Total Image”, the spectator encounters the essence of Van Gogh, just as they encounter their own essence. What is being narrated is not a linear storyline, not a plot with a beginning, middle and end but the terms with which we encounter the infinite, the essential. We can extrapolate that the exhibition is narrating Van Gogh’s essence, it’s essential, universal quality, as his paintings are made continuous and ongoing, as they align with the complete capture of the photographic, and its redeployment as endless playback.

N: The exhibition program also states that the spectator is liberated from all habits and constraints in a viewing experience “where there is no center or periphery” where they are “free to roam”, guided only by “whatever they choose”, “inspiration” and “emotion”. Judging by the relative stasis of spectators, though, I have to wonder about this idea of liberation. The projected images seemed to only reinforce my passive engagement with digital image playback

K: There we were, with this incredible proposition to liberate ourselves from our habits, but somehow stuck with an image that had already gotten as close as one could get, that had already captured the essence of the image in photographic form, so that whatever uncertainty, or undecidability, between imagery and painted topography, the materiality of paint and the effects of light, had already been decided or smoothed over. Just like the sound, continuous in an endless smoothing over that meant that we could see and hear in only one way, or at least in a very reduced way. This creates the sense that whatever specific tendencies of seeing that only an inhabited body can develop and transform, become irrelevant.

K: If I had been in the exhibit by myself, I might have felt that I was drowning in his images, sick from the incessant movement that had so little to do with the movement within the brush strokes, the topographies of screens or paintings, or in the forms depicted by images. As we were disoriented by the still and moving images on floors and walls, the inescapable familiarity of melodies instantiated a perceptual kind of holding in tact, a melodic ebb and flow in a directionality we had no control over.

K: And I think I can say

N: this

it’s not that either of us

ever wanted complete

control, just that when our gaze is

automated to the extent that it can seem to land everywhere and all at once, a different kind

of control is imposed on the viewing experience,

not one that emerges from the material and situated quality of inhabiting a space, but one where the space and the body are meaningless

and have no capacity to surprise us,

or allow us to reflect on how having a body

informs ways of seeing

the longer we remain in the exhibition space

the more we experienced an ever-mounting inertia— the sense that how we view the images

has already been choreographed

as a kind of automated vision

most frustratingly, rather than attempt to amplify the the dynamic tensions

between gestural traces and the plastic thickness of paint,

or the heterochronicity with which figures,

contours and patterns emerge

from the dense textures of the painted works,

the automated temporality of the “Total Image”

reduced all of this to something

predictable and mundane.

K: the whole thing makes me wonder why

N: the Imagine Van Gogh project abandoned more distinctly situated projection sites like quarries of Baux en Provence, or the long and narrow format of the Japanese ‘okio-e’ format. I would have loved a chance to measure those images by the time of walking alongside them, where the difference between the length of the screen and the constrained directionality on my path would have made think-able, the way certain images can grip on movement and attention, the way the image of painted brush strokes can appear to gather up the surface into the image of a cat, lurching, momentarily, before disappearing again into the grassy field. Or how the repeated convergence of semi-circular brush strokes and thickly layered, multi-colour paint can suddenly give way to the image of foliage spreading outwards, while holding onto a specific instance of painted form.

K: I imagine the quarries to have an irregular topography dividing and distorting the projected image on a complex geometry, or having irregular reflectivity and darkness or lightness, making visible the materiality of the projected image, of light and screen, dampening the idea that photography can reduce bodies to images in favor of something else—a way of reimagining recognition in time and beyond image capture.

N: Absolutely, all of that sounds so inspiring.

K: I do think, though, that there were a few instances during our Imagine Van Gogh experience that gave rise to something like what you are describing, even if overall it was overwhelmingly static. For instance,

N: when the projection of the various painted scenes (whose variety is underlined by their differing scale and the difference between movement and stasis) simultaneously breaks, and all the surfaces of the space are suddenly articulated by a unifying appearance like the graphic, grey-scale of charcoal sketches. The dramatic effect of this break creates an indeterminacy, where the light of the projection seems to acquire a material status that is more impactful than the painterly articulations of the projected image. In these instances, the projected image is no longer mere documentation but emerges transversally—between floor, screen, painting, high-resolution digital photograph and projector, spectator, the surface of skin and breath.

K: I was disappointed at how quickly these animate breaks were, so quickly subsumed by the out-of-the-box sequences of play-back between pause, close-up and slow pan.

N: What I want is to not be by myself in this space, to not be held in tact by this predictable unfolding. Here, with you, in thought, in light, in paint, in the desire, for the possibility to not be bound to a pre-existing idea of myself, I don’t want a freedom that is separable from you. I want to forget myself in this space, to become something else, not as a condition of my freedom, but in moving together, in time, in hesitation, in an uncertain exchange that is more than I could ever imagine.

N: Knowing what I do about Vincent from his letters, I wondered what he would have thought about this exhibition.

K: I wondered too, about the people wandering through the images, as I was with you, Nicole. Why were they there? What did they think? Was it possible to be critical when consumed by the pre-fab emotions filling our ears? Did we discover anything new about Vincent and his work through this experience?

N: Or is the repetition of ideas, of what we already know, simply reinforcing our bias? Or so-called knowledge and understanding. The exhibit is entitled “Imagine Van Gogh”, but what is left to imagine?

K: At one point in the loop of images there are poppies swaying in the breeze, as film footage placed amongst Vincent’s painted poppies. It’s the only moment I saw film footage introduced, and my mind went to yet another popular film reference: Soylent Green. The scene where the character Roth seeks government assisted suicide, and is put in a comfortable bed as he watches on IMAX sized screens the world as it was before humans destroyed it.

Maybe tragedy is all we can imagine at the moment. The end of the world.

Or maybe we can only imagine what is presented for us to imagine by cinematic capture.

Maybe this exhibit tells us where it began for us with industrialization, alienation in modern times, the escalation of mental health problems, virtual noise and endless looping of images.

Maybe the “Total Image” reveals itself, as a logic surveillant governmentality where the

image is synonymous with the complete capture of the individual.

Or, maybe we, and the institutions presenting this work, can only imagine how to retell the same story again, of one man, his journey, and an aesthetic connected to ticket sales. If we try another version, can we change that?

Yes,

since the narrative of Van Gogh, his life and images, is already so entrenched, so

pre-packaged so saleable.

N: Well perhaps that in itself is a Proposition: How can we tune-out the essentializing romanticism of the music, the mundane automation of the projection loop and the monumentalism ideal of total capture long enough for a getting close that exceeds Van Gogh as icon and the stasis that history affords this status, the scalability of the image, or even referentiality to the work itself?

The subtle, unintended undulations

of the vast projection screens as,

the space

of contact between screen and floor

and a singular kink in the screen that, although small,

undulated and distorted the projected image enough

to imagine where one could

begin to experiment with the fissures of the “Total Image”.

What fissures, folds, and edges disrupt the making of a totality and propose the possibility for something else more fugitive? How can we gesture in excess of the “Total” and an idea of total capture, whether of artworks or individuals? How can conversation, speech and heterogeneous corporealities, between image and sense, erupt between and across the fissures?

KN K N NK: And in this conversation, dialogue becomes a means of fissure as well. Dialogue allows for experimenting with continuities and discontinuities of thought whose authorship is undecided. Thought surfaces, shallows and submerges between and across the exchange of dialogue, in the tension with which dialogue steadies and demarcates authorship, only to give way to the possibilities of multi-authored continuity within parts demarcated as single-authored. Thought erupts as a collaborative improvisation within, between and across sentences. The fissures become a means of inhabiting thought that is not ours, of making thinkable how thought and authorship always exceeds a transparent and singular lineage of cause and effect. Our undecided authorship slows and steadys just as it quickly transports us to new sides of things.

Nicole De Brabandere is currently a visiting researcher at McGill University in Montreal and works at the intersection of research-creation, experimental media practice and embodiment. She recently published the article ‘Drawing Light: Gesture and Suspense in the Weave’ (European Journal of Media Studies (NECSUS) _#Gesture, 2019) and her current projects include Rhythms of Care and Co-presence in Robotic Milking Infrastructures and Animating Impersonal Affections in the A.I. Renderings of ‘This Person Does Not Exist’.

Kathleen Reichelt writes for stage and film, creating dialogue and characters that centre on philosophy, relationships and art. Her visual art has been published in Maintenant: a journal of contemporary DADA (Three Rooms Press, NYC) and is part of the permanent collection of the Asia Culture Center in Gwangju, South Korea. The artist is part of the poetry performance project Burning Iceberg, co-director of the Thousand Islands Film & Stage and co-founder of 253469.