Being and Imagination: Robert Pepper’s Intangible Reflections, 2015-2018

Daniel Barbiero

February 2019

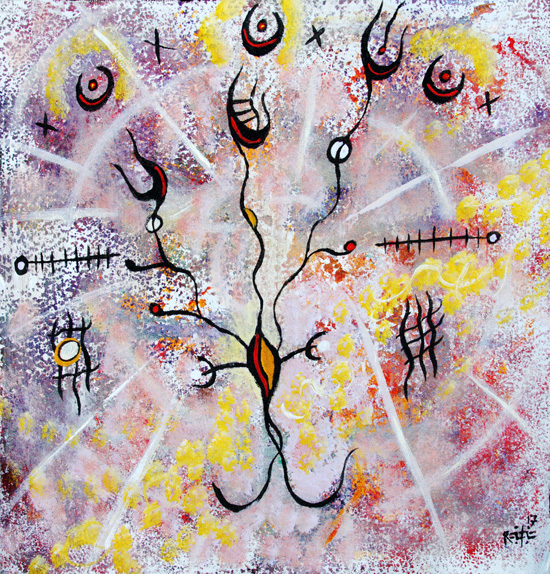

Doors of the Architect, 2017, all images courtesy of the artist

Doors of the Architect, 2017, all images courtesy of the artist

Sometimes the surest—or at least the most revealing—grasp of the real comes through the imaginary. But to attempt to apprehend the real through the imaginary is to take a risk. It is a risk endemic to art. Robert Pepper’s Intangible Reflections, a collection of acrylic on canvas works painted between 2015 and 2018, is an encyclopedia of the geography, fauna and language of an imaginary world overlapping with the everyday world we all hold more or less in common. Intangible Reflections ran as a solo show at the Pleiades Gallery in New York in December of last year; the paintings have also been reproduced in a fine, full-color catalogue that gives a good sense of each picture’s presence.

The majority of paintings in Intangible Reflections depict complex, unidentifiable curvilinear figures that seem to pulsate with life. These biomorphic creatures, painted with vivid reds, purples, greens, yellows and oranges, are marked by randomly distributed eyes, mouths, limbs and cilia; we seem to be able to see inside of them at the same time that we see them from the outside. Their boundaries are as ambiguous as their identity. Many of them are emblematized by DNA-like, helical structures and strange characters reminiscent of the supposed Martian alphabet channeled by the French medium Hélène Smith or the symbols alchemists employed to encrypt the records of their work. Beyond their allusive interest, these marks seem to imply a vision of biological form as the concrete embodiment of strings of information. If the information in question is hypothetical or outright invention, so much the better: these are imaginary beings, after all.

In choosing biomorphs as the means of giving form to his imaginary beings, Pepper draws on a tradition of visual art that flourished most notably in the mid-20th century with works associated with abstract Surrealism and proto-Abstract Expressionism. As with these works, Pepper’s contain figures that suggest living things by—paradoxically—refusing to be confined to the forms of any living things in particular. In their refusal, Pepper’s beings break the link between form and facticity that is the inheritance of evolutionary pressures on actual living things. These creatures are imaginary but plausible as primordial forms of life suspended in a microscopic liquid environment or—at the other end of the scale—they could be vast, world-encompassing entities similar to André Breton’s Great Transparents. Without an exterior measure by which to judge them, their scale is undeterminable—which just enhances their utility as symbols.

Song of Ramulaud, 2016

Song of Ramulaud, 2016

It isn’t only an ambiguity of scale that distinguishes these figures; it is an ambiguity of meaning as well. But that is something inherent in biomorphic imagery generally. By representing no particular thing, the biomorphic figure serves as a kind of limited cipher emblematizing all living things regardless of type. Distinctions of species, genus, family, order—all of these taxonomical categories are individually negated and subsumed into a larger, relatively undefined category belonging to a generalizing intuition rather than to a precisely delineated method of identification and sorting. The biomorphic image, like many mythic images and figures, suggests rather than asserts and thus can be read in a number of ways; it belongs to no existing type of animal and indeed only hints at being an animal at all. What it is it is by inference and even sympathy. Biomorphic images clearly are meaningful but their meaning is implicit and often condensed and polyvalent, affording a richness of simultaneous, and even contradictory, interpretations.

To the extent that it is such a cipher whose content can be read through any of a number of possibilities, the biomorph simply signifies what all of these possibilities have in common (and, in the case of imaginary beings, what they might have in common), which is to say the basic functions, powers and vulnerabilities of living things, all of which must act to survive and are ultimately subject to individual extinction. At its most reductive, this can be expressed as the basic action that Walter Burkert, in describing the elementary narrative structure of myth, characterized as “to get.” This is, in other words, the basic existential structure of coming into the world as a lack and consequently projecting outward in pursuit of finding and assimilating whatever it is that will make good that lack. Through the figure of the biomorph we can see, in schematic form, as it were, that rudimentary, general pattern of action underlying human—and animal—behaviors even in their particular complexity. It is in terms of this fundamental, existential experience of lack and satisfaction, of desire and fulfillment, an experience structured as a perpetually repeating cycle and thus as a perennial dilemma, that the basic meaning of the biomorph can be divined.

Biomorphic figures indirectly refer to this pattern of action by hinting at the physical substrate—the material condition of having or being a body—that makes it necessary. To have or to be a body is to be subject to the pattern need-satiation. By seeming to symbolize the perennial dilemma acted out through the cycle of need-satiation, biomorphic figures signify in an irreducible, if in an as yet undifferentiated, way—a way that, not incidentally, can be reframed in terms of human existence. That these particular biomorphs represent imaginary beings is no impediment to interpreting them in human terms; as imaginary beings they have the effect of making us see the human in terms of the primordial, something that mythic figures often do.

Anatalia, 2017

Anatalia, 2017

The biomorphs of Intangible Reflections link the primordial human to the imaginary through the linkage of analogy. An associative relationship of likeness forges a connection between the imagined being and the real form of life: the similarity in structure between the living form and the imaginary form establishes a hypothetical similarity in functions and modes of being, with all that that implies in terms of motivations, needs, desires and, in short, whatever kind of inner or instinctive life we feel licensed to ascribe to another animate object. Through this kind of analogy the imaginary becomes the real not through a simple comparison but rather through an inferential transfer of qualities. This biomorphic analogy or association doesn’t necessarily set up a vertical connection between beings—it doesn’t bind higher to lower forms of life—but instead sets up a horizontal correspondence between orders of being whose organic makeup is the leveling factor. Thus the link between the real and the imaginary orders of being consists in a symmetrical, lateral association.

And it is through such a lateral analogy or correspondence based on structure that the superficially absurd contradiction between the real and the imaginary reveals itself to be in a fact a profound connection. By mimicking the general appearance and features of a living being, the biomorphic figure takes the unfamiliar or uncanny—the imaginary beings Pepper takes as his subjects—and covers it with a shape that, if not like anything we’ve actually encountered before, at least bears a reasonable family resemblance to something we know as intimately as our own body. If the body, with its drives and functions, provides the most fundamental revelation of what it is to be a living thing the biomorph, by substituting a kind of adumbrated morphology for the properly articulated human—and by extension, other animal—form, condenses the meaning of that revelation and thereby highlights or amplifies certain features which—consequently—symbolize the generalized condition of being thrown into a world where those drives and functions must be enacted and resolved. In the end, then, what Pepper’s imaginary Intangible Reflections reflect is the irreducibly tangible condition of being in the real world.

Flowers in Squared Circles, 2016

Flowers in Squared Circles, 2016

◊

Daniel Barbiero is an improvising double bassist who composes graphic scores and writes on music, art and related subjects. He is a regular contributor to Avant Music News and Perfect Sound Forever. His recent releases include Non-places, with Cristiano Bocci, and Fifteen Miniatures for Prepared Double Bass.

To read more by Daniel Barbiero on Arteidolia →