Paris 1874: The Impressionist Moment

Daniel Barbiero

November 2024

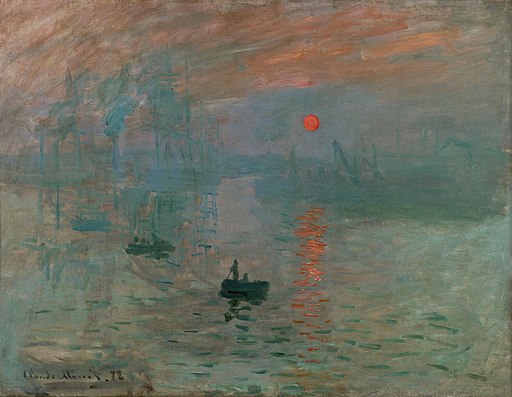

Monet, Sunrise, 1872. Oil on canvas, 48 × 63 cm. Musée Marmottan Monet, Paris

Monet, Sunrise, 1872. Oil on canvas, 48 × 63 cm. Musée Marmottan Monet, Paris

Paris 1874: The Impressionist Moment, an exhibition jointly organized by the US National Gallery of Art and the Musée d’Orsay of Paris, brings together work from two opposed sides of late 19th century French art: the country’s officially recognized artists, and the dissident artists who would become known as the Impressionists. The focus of the exhibition is on work originally shown in 1874 in two very different contexts, the Paris Salon, and the self-produced event that has come to be known as the first showing of Impressionist art. By bringing together work from both these shows, along with photographs and other illustrations depicting the city during the tumultuous years just prior, Paris 1874 allows us to see the contrasts between the two varieties of art – official and dissident – as well as the historical context in which they competed.

Eighteen seventy-four was the year the Société Anonyme Coopérative des Artistes Peintres, Sculpteurs, Graveurs, a group of artists formed in a gesture of independence from Paris’ official artworld, held its initial exhibition. In contrast to the Paris Salon, the annual juried exhibition organized by the French Academy of Painting and Sculpture for the work of artists given official recognition by France’s cultural establishment, the Société Anonyme’s unjuried, self-curated exhibition represented a counter- or anti-Salon for art and artists largely ignored or rejected by France’s institutional gatekeepers. Among the Société Anonyme’s artists were many who became respected figures in the development of Western art: Renoir, Monet, Cézanne, Berthe Morisot, Pissarro, and Degas. At the time, though, they were marginal figures whose anti-Salon, held at the studio of the photographer Nadar, was a commercial and critical failure. It was the art shown at the Salon that was more attuned to the tastes of the time. An interesting time, to be sure: Paris had only recently been resurrected from a lost war, collapsed empire, and abortive revolution.

In fact some of the most striking items on display aren’t artworks from either exhibition but rather are the photographs and engraved illustrations depicting Paris during and in the aftermath of the recently concluded Franco-Prussian War of 1870-1871. The war, needlessly provoked by Emperor Napoleon III, was catastrophic for France. Its incompetently led army having been defeated in the field and its empire consequently having imploded like the empty shell it was, its capital city underwent a long and devastating siege and then suffered a bitter civil war that left it in ruins. Images from Paris 1874’s documentary materials bear witness to the extent of the destruction both physical and human: shells of houses open to the sky; piles of rubble, shattered trees, and broken bits of architecture in the streets; barricades with dead bodies lying behind them; and finally firing squads for the civil war’s losers. The disaster cut lasting scars in France’s social and political life. Out of this chaos something approaching normalcy emerged, and the city’s cultural life emerged with it.

As the exhibit’s selection of works from the Salon shows, the official art of the postwar period maintained a traditionalist continuity despite the upheavals of the recent past. The paintings and sculptures largely hold to themes from history, mythology, the classical world, and religion, and do so with a painterly rhetoric stolidly built on attention to observable detail and factual accuracy. Official art had assimilated many of the lessons of the realism of previous decades, and if much of it looks sterile or inflated to us now, we can at least acknowledge its technical excellence and capacity to give a kind of objective presence to the tableaux it depicted. William-Adolphe Bouguereau’s Homer and His Guide, a scene from an imagined Greek antiquity, shows the blind poet being led by a shepherd boy while a dog turns to bark at him. The interlaced fingers of the hands of the boy and the poet, the expression of the boy as he looks anxiously at the dog, the details of both figures’ clothing and bare feet – all of these are finely wrought, even if the picture overall leaves us emotionally uninvolved. Auguste Lançon’s Dead in Line! is a history painting showing the grisly reality of modern war: in the foreground the bodies and scattered kit of French marines killed in the September 1870 Battle of Bazeilles lie in the road, while in the background the village burns and the Bavarian troops they fought go about their business indifferent to the scene of carnage. Lançon’s realism, which doesn’t shy away from showing the discoloration of the corpses, some of whose boots have been stripped off, is gruesomely compelling and, intentionally or not, subversive of the notion of the glory of war. The winner of the 1874 Salon’s Medal of Honor was another history picture, L’Eminence Grise by Jean-Léon Gérôme. This painting is set in the interior of Cardinal Richelieu’s palace where Richelieu’s plainly dressed advisor, the Capuchin François Le Clerc de Tremblay, descends a staircase while absorbed in a book. Meanwhile several richly dressed officials or aristocrats ascending the stairs stop to bow low and remove their hats. The scene is portrayed in precise and sober detail, but the effect of the aristocrats’ ostentatious display of deference to the ostentatiously modest power-behind-the-power is, at least to modern sensibilities, slightly comical.

How does the work of the anti-Salon compare? One hundred and fifty years and many reproductions and merchandisings of their work later, it just isn’t possible to see the Société Anonyme artists’ challenge to official art the way a viewer would’ve seen it in 1874. Whatever radicalism it had was domesticated a long time ago; what once was revolutionary now is familiar or worse, beloved. Still, we can get a sense of how the dissident artists broke with tradition and in effect refounded art for the next century.

First off, we can see what we might call, to borrow a concept from the late philosopher Gianni Vattimo, their “weakening” of vision – their shunning of the grand narrative in favor of the tentative or circumspect interpretation. Just by being about what they were about, many of the Salon’s paintings seem to announce their significance even when their subjects are depicted in a realistically matter-of-fact and non-idealizing manner. By contrast, the Société Anonyme’s artists depicted domestic scenes out of contemporary bourgeois life. They rejected public spectacle for private sensation; the grand oration for the intimate conversation; the encyclopedia for the diary: in effect, they replaced the epic with the lyric and substituted the subjective response for the objective fact. This modesty or weakening of vision goes far toward explaining their eventual popularity. Paris 1874 includes a number of their works along this line which have become iconic: Berthe Morisot’s The Cradle, a painting of a young mother looking at her sleeping child; Renoir’s portrait of a well-dressed woman in The Theater Box and his young ballerina in The Dancer; Monet’s mother (or nanny) and child sitting by an iron gate in The Railway; Degas’ At the Races in the Countryside, and of course Monet’s Impression, Sunrise, the once-mocked painting from which the Impressionists got their name. Part of Impressionism’s continuing appeal, I think, is that it tends to inspire in viewers a state of anemoia – the nostalgia for a past that isn’t one’s own – and perhaps even envy for the seemingly more elegant and decorous time its artworks depict, whatever the reality on the ground actually was. Which raises the question of whether some of the pleasure we derive from these paintings may be based as much on a misreading as on anything else.

A second and no less integral part of the dissident artists’ weak vision consisted in their extending and transforming realism’s commitment to the observation of detail into a rendering of experience as an unstable flux of perceptions along with their allied sensations. Their art is as much about the small and momentary effects – both visual and felt –of light and color as it is about whatever objects or events are being shown. Their work assumes a certain metaphysic that reveals itself through seductive visual details – a kind of phenomenology of the pleasure principle. This concern to convey the transience of perception and sensation is what separates their appropriation of realism from the realism of the Salon’s artists and brings them in line with Baudelaire’s declaration that “modernity is the transitory, the fugitive, the contingent.” Hence the conventional wisdom that the 1874 anti-Salon announced the birth not only of Impressionism, but of modernism in art as well. (Just because wisdom is conventional doesn’t automatically make it wrong.) The Impressionists’ dissolving of solid bodies within the fleeting play of light made possible the more radical experiments of Futurism; Cézanne’s leveraging of atmosphere to reduce things to their geometries opened the way for Cubism’s unsettling reconfiguration of objects within the perceptual field. Paris 1874 helps us to see why the art of the Salon really did represent the past while the art of the dissidents pointed toward the future, and that 20th century art in fact began there, in the 19th century.

Paris 1874: The Impressionist Moment

National Gallery of Art, Washington DC

September 8, 2024 – January 9, 2025

For more information on Paris 1874: The Impressionist Moment→

Daniel Barbiero is a double bassist, composer and writer in the Washington DC area. He writes on the art, music and literature of the classic avant-gardes of the 20th century and on contemporary work, and is the author of the essay collection As Within, So Without (Arteidolia Press, 2021).

Link to Daniel Barbiero’s, As Within, so Without →