Review: “The Williamsburg Avant-Garde”

patrick brennan

June 2023

On Cisco Bradley’s The Williamsburg Avant-Garde:

Experimental Music and Sound on the Brooklyn Waterfront

Duke University Press, 2023

If a visitor were to walk today through the riverine Brooklyn neighborhood of Williamsburg for the first time, there would remain hardly a clue of what had vigorously pulsed through those streets not so very long ago. Cisco Bradley, Associate Professor of History at Pratt Institute, has accomplished an archeological compendium of experimental musical, social and artistic activity from 1988-2014 with his new book The Williamsburg Avant-Garde. He plies the role here of an Ishmael, but an Ishmael as microphone who, even when paraphrasing, allows the voices from his more than 200 interviews with those who were actually there to represent their own experiences and perspectives, more a peoples’ history than the sort of triumphal celebrity narratives customarily after the fact wrapped around once upon a time underground art and music scenes.

I learned about Cisco’s work in progress when he contacted me for details about one of the projects that I happened to have presented in Williamsburg. Having operated often enough on even the margins of New York’s musical marginalia since the mid 70s, I can recognize as familiar the worlds he describes in his telling, which achieves more than an accuracy, but some degree of truthfulness, in solidarity with what these ever shifting mileus can mean for the musicians. Without the broad, inclusive perspective of such a document as this, all that could likely remain might be a scattering of individual recollections en route to the garbage bin of forgotten histories.

Besides, even if you had been there, it would be close to impossible to be present at everything that went on during this 26 year period. I witnessed some great music in this neighborhood, but a whole lot went on that I didn’t even have a clue about, and I’m appreciative that so much can be retrospectively located through this book.

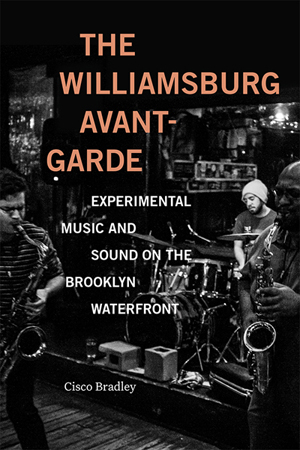

One of the most important strengths of The Williamsburg Avant-Garde is that it elaborates with equal care, regardless of idiom or generation, on the intentions, ideas and aesthetic strategies of the highly diverse range of artists who could find a platform there. This is not ephemeral and has enduring resource value for musicians and listeners in terms of discoveries and developments to come. He supplements this with a substantive discography that delivers the vital body of physical evidence. (Right now, I’m checking out the ecstatic and carefully coordinated music of Little Women — the quartet whose photo appears on the front cover, whom I’d never caught live.) What makes Bradley’s archeology at the same time so urgently contemporary is that so many of the artists covered are alive and active right now, even if a good number of them may still be underground.

The term avant-garde has become over time a somewhat slippery one that’s sometimes employed as a stylistic marker for music whose ideas are no longer “avant” in the sense of discovering something genuinely new, but Bradley adheres as much as possible to the original spirit of this term. He notes how a pluralistic generational experience during this period inclined toward dissolving genre distinctions and digging deep into cross pollination for its innovative potentials.

Genre, whatever its magnetism, greets a listener as something as if already whole, established, and predetermined, but, especially from the perspective of putting sounds together, this surface appearance can be perceived as the artificial construct it actually is: a provisional environment glued together from distinctive combinations of vocabulary, method, sound quality and community expectations. Once broken down into its components, any of these may be resituated in novel contexts and generate unforeseen possibilities. Such recombinant potential is commonplace in many evolutions of music and other arts, not to mention, say, in cooking. It’s less any of the specific “whats” in play than the “hows” involved.

Williamsburg was no island and participated in and continued this propensity to mix things up that had already been happening, as demonstrated by the stylistic pluralism welcomed and nurtured at, for example, the original Knitting Factory on Houston Street in Manhattan. What many of the musicians coming through Williamsburg especially seized upon was improvisation as a conduit among a heterogeneity of knowledge pools, interfacing lexicons and attitudes developed through otherwise seemingly incompatible nexuses like Postpunk, Free Jazz, Noise, Euroclassical modernism, Indie Rock, DJ and other electronic sound generation — not to mention multimedia.

Like many neighborhoods, Williamsburg had long been awarded with what Ruth Wilson Gilmore has aptly termed organized abandonment. A majority of residents had been getting by with pretty minimal resources. Warehouses and factory spaces were more vacant than not. Rent was low, and because of that, visual artists gravitated there and moved in. In 1981, guitarist Gerry Eastman opened Brooklyn’s only Black-owned and musician-run nonprofit jazz club, the Williamsburg Music Center, on Bedford Avenue. Critical mass accrued toward the end of that decade and spontaneous combustion ignited informal gathering places that hosted performances and events, many deeply informed by DIY Punk aesthetics. People got so ambitious that they occupied abandoned buildings to stage large, outrageously spectacular events. 1997 introduced a local pirate micro-radio station, Free 103point9, that grew into a major hub for local music performance. As Williamsburg crept toward fashionability, these opportunites dwindled, and music migrated more into clubs, cafés and galleries. Eventually, as so many locations had to shut down, focus narrowed toward a single venue, Zebulon, which offered an unusual degree of support to innovative musicians until its closing in 2012. A few sites hung on into 2014, and that was about it.

Williamsburg flourished primarily because, for a good while, the meter wasn’t running all that exorbitantly on the free flow of sociality. This is important because, no matter how much introspection and solitary effort may be required, art is irredeemably social — and in this sense interdependent. Without audience, which includes interchanges with other artists and their work, the meaning of what one does is left suspended. It’s not at all mysterious or complicated that artists tend to gather in places where multiple ideas and perspectives can ferment. It’s about the people.

This story of Williamsburg may be specific, but it’s also not unique in playing out a script that had already been perfected in Manhattan and internationally distributed. Its short term as a creative flashpoint poignantly demonstrates the adversarial and destructive role played by that slow motion tsunami known as gentrification, and Bradley never hides its pernicious influence. It was the accelerated gentrification of Lower Manhattan that dispersed one of the most pedestrian friendly, face to face artistic milieus in North America. Without that forced exodus, whatever might have happened in Williamsburg would have gone differently. The municipal unleashing of the developer class upon Williamsburg wiped the area “clean” within a decade with glass striated megatowers for refrigerating the minions of the imperial financial elite.

In continuity with principles enshrined in the 1493 Doctrine of Discovery, gentrification’s fundamental social mission can be best understood as one of replacing putatively inconvenient persons and interactions with more predictably “market ready” settlers by prohibitively multiplying the costs of living or working in a particular area, which is to say it’s a method of social engineering effected under the genteel cover of purportedly impartial market dictates. In this respect, the low wealth Boriqua families who’d lived in Williamsburg for generations and the slim margined artists who were already being pushed out of Lower Manhattan were regarded as equally disposable placeholders by the well financed reconquistadores who followed. All perfectly legal, of course.

As a lawyer once explained to me, “law is a blunt instrument.” The very concept of legality seems to necessarily presuppose criminalization and exclusion. The U.S., for example, sports its own notable track record of having decreed people of African descent, women, Indigenous people, LBGTQ+ persons, young people, striking workers, immigrants, or people without a place to live as innately illegal till somehow “proven” otherwise. New York City’s 1926 cabaret laws banned dancing without a permit in bars for 91 years and from 1940 to 1967 instituted a pass law system that required musicians to carry valid cabaret cards simply in order to work at all almost anywhere within the city limits.

In contrast, gangsters and other folk “outside the law” have often been directly or indirectly supportive of artistic flowering, whether that be the Medici in Renaissance Italy or the famously corrupt Pendergast mayorality in Kansas City where Charlie Parker grew up and Basie flourished. The sly winks at the law in the New Orleans Storyville district fostered music there in a way that has never since been replaced.

It seems that informal socializing of almost any sort in public spaces strikes terror into the moneyed classes and their uniformed armed bureaucrats. The threats posed by unlicensed alcohol sales and low budget fire code violating public gatherings seem to be perceived as on par with “weapons of mass destruction.” Yet, it’s exactly this not profit driven informality of interpersonal contact that most fosters creative community and invention. In enforcing property rights over people, law manages to devise plausibly deniable methods of reducing constitutionally proclaimed access to freedom of expression, assembly and association (and by extension, freedom of thought and imagination) to lip service. This is exactly why the dynamics of a music scene such as Williamsburg, besides the music itself, becomes such an important story to tell.

Bradley’s volume is encyclopedic and without fluff. To list a few names and places here won’t substitute for the genuine article. But, his afterword Art, Experiment, and Capital, where he interprets these events within the larger social context, has so much to offer that it’s tempting to quote it in its entirety. He argues that the frankly solipsistic, well capitalized ideology that willfully conflates exchange value with cultural value has artificially pushed the United States toward the brink of creative stagnation, a feat of cannibalism that reminds me of Goya’s Saturn Devouring his Children. He quotes artist Andrea Fraser: “We’re in the midst of a total corporatization and marketization of the artistic field and the historic loss of autonomy won through more than a century of struggle.”

The Williamsburg Avant-Garde is most, however, a powerful celebration of what Bradley has depicted as “a snapshot of the possibilities of human artistic vision and imagination,” which are symptomatic of an ongoing refusal to settle for — or comply with — impoverished, top down, technocratic prescriptions regarding the meanings and value of human relatedness. As he concludes, “it is in the outer edges of sense that we encounter our most brilliant and startling discoveries.” The horizon is never over.

◊

New York City composer, saxophonist & bandleader patrick brennan has been pursuing a contrarian and independent path for four decades in rapport with the Blues Continuum toward a distinct multidirectional musical language. Among his many recordings are tilting curvaceous (Clean Feed, 2023) with his ensemble s0nic 0penings, terraphonia (Creative Sources, 2018) with Portuguese electroacoustic improviser Abdul Moimême and Sudani (deep dish, 2000) with Gnawan Ma’alem Najib Soudani of Essaouira, Morocco. He’s author of Ways & Sounds (Arteidolia Press, 2021), an inquiry into some of the formal implications of music’s internal social interactions for composition & listening. He writes about music, cinema, visual art & poetry.

Read other articles by patrick brennan on Arteidolia→