Forty Erasers Attack Valuable Drawing

Sandy Kinnee

May 2021

Erased de Kooning, San Francisco Museum of Modern Art

Erased de Kooning, San Francisco Museum of Modern Art

Creating with an Eraser

He rubbed all day and night

for two weeks

Used up 40 Art Gum erasers

Still he could not wear away

The title

Erased de Kooning Drawing

I erased my own titles

one by

One

Keeping the paintings

Forty Erasers Attack Valuable Drawing

On a cool morning, with a touch of winter in the air, it can make us smile to see evidence of our own breath. It surprises us when we see our own breath made visible. We take air for granted; we do not have to see it. Some art is like air. Robert Rauschenberg’s white on white paintings and his “Erased de Kooning Drawing” are artworks we do not need to see to understand. The concept satisfies our minds, well enough to bypass our eyes. The weight of these artworks is not physical, but completely conceptual. Yet, they do exist as objects.

Robert Rauschenberg painstakingly erased a Willem de Kooning drawing, producing the infamous “Erased de Kooning Drawing”, of 1953. One action obliterated another act, creating while destroying, making while undoing. It was as bold as it was blasphemous.

The “Erased de Kooning Drawing” is known mainly to artists and modernists.

Amongst this group it is legendary. However, few among them have seen it, and fewer still have stood before the framed artifact and examined it in detail. No postcard or poster exists for the artwork. No art history textbook holds an illustration. It is invisible. It is mythic. It is assumed to be blank.

The legend of the erased drawing is known thanks to Off the Wall by Calvin Tomkins. The Tomkins book devotes about 300 words to Rauschenberg’s recounting of how the piece came into being. One single sentence describes the resulting artwork. More mention is given the frame.

Apparently the shock of the deed and the labor invested are all we need to know. There is nothing to see, just some lines that are not there anymore. It is like pointing to the spot where you saw your breath one crisp November morning. Or so it would seem. Or so you might think.

Robert Rauschenberg had recently made his white paintings, reducing the act of painting to a purely physical act of applying white paint to a support. The gallery where these paintings would be shown may not have been confident that any would sell. So, the gallery asked Rauschenberg for some drawings, in the hopes that the drawings would be saleable. Rauschenberg would ultimately frustrate that goal. He wanted to make compatible drawings to exhibit with the white paintings. While the white paintings may have looked blank they were not. They were about the application of traditional paint on a traditional support.

These paintings anticipated Marshall McLuhan’s “the medium is the message”.

How could one make a drawing which both gave evidence of mark making, yet showing nothing? No one had before made a drawing entirely with an eraser, so Rauschenberg gave it a try. Rauschenberg’s initial efforts were inglorious. They looked like nothing more than the blank sheets of paper they were. He decided he needed to erase a drawing. Rauschenberg, a relative newcomer to the New York art scene, knew that erasing his own work would signify nothing. His work had no established market value. Erasing all or part of one’s own work was part of art making. A spoiled drawing was a wasted sheet of paper. It meant nothing. Erasing something of no value was meaningless. He had to erase something that mattered.

Then he had a breakthrough idea. If he erased a drawing by a recognized artist, he would have a drawing that fit conceptually with the white paintings, while still retaining the association of having been a drawing by a better-known artist. Additionally he would accrue the side benefit of support or blessing from that recognized artist and a narrative to support his legend making achievement.

Erasing the work of a respected artist also held shock value. Shock has serious value.

He knew a successful artist, Willem de Kooning. Willem de Kooning was an established master with market value to each artwork he produced.

Rauschenberg admits to sneaking into de Kooning’s studio and stealing a drawing. But a stolen drawing, even if he had stolen it for the purpose of erasing it, which is unlikely, would not have given him the validation only de Kooning could bestow onto the project. He approached “Bill”, as he familiarly called de Kooning, with his idea of creating a drawing purely by erasing. I find it interesting that Willem de Kooning is never directly quoted, except by Rauschenberg, on the subject of the erased drawing. He is quiet. At any point, de Kooning could have taken the last laugh and disowned the drawing, called the erased drawing a hoax. But he did not.

Rauschenberg informs us, through his interviewers, that he asked Bill for a drawing that he would miss, one dear to him, a prize. He also wanted one that would demonstrate his prowess at erasing. Did de Kooning select a very difficult, hard to erase drawing to challenge Rauschenberg’s skill at erasing? Rauschenberg asserts that his was not mere erasing, but Herculean effacing. I will get back to this later. In any case de Kooning provided a drawing, for the purpose of erasing it. This gift to Rauschenberg of a drawing makes de Kooning more than an accomplice. He is a powerful, but silent partner.

To efface the work of a known artist is an act of vandalism, desecration. It is like burning money, but irreplaceable. It is also a statement: In this case a superb statement of contradiction in the spirit of Duchampian Dada. It is both an artwork and a destroyed artwork at once.

I do not recall exactly when I first heard of the Rauschenberg “Erased de Kooning Drawing”, but it was in art school, long before the Tompkins book was published. What I first heard was like art school gossip. It was a word-of-mouth legend, like the story of Jackson Pollock pissing into Peggy Guggenheim’s fireplace. No one really knew why Pollock peed. Was he making a gesture or too plastered to know it was not a urinal? What mattered was that Peggy Guggenheim noticed.

As I heard it, Robert Rauschenberg made a drawing by erasing a de Kooning drawing. It sounded odd, rule-breaking, and delicious. The erased drawing sounded gesture and artifact rich. The art world noticed.

I remember later wondering if Rauschenberg had kept the erasures from the de Kooning. They would have been microscopic de Koonings, of a sort. Each tiny erasure fragment would have been embedded with pigment laid down by de Kooning. I pictured in my mind a small glass box filled with crumbled, dirty, erasure residue. But the idea of saving the byproduct probably did not occur to Rauschenberg. He was probably too busy sweeping up.

In the erased drawing de Kooning is not mocked, only used to make a point that a drawing can be made by erasing a drawing. When Rauschenberg finished erasing the de Kooning he said he felt the result was successful. There would be no point in making the same point again. “Erased de Kooning Drawing” is a case where the seminal piece has been made.

All of the above was written with a knowledge uninformed by seeing the actual artwork. I knew no one who had seen the erased drawing. Rauschenberg’s “Erased de Kooning Drawing” could as easily have been a total fabrication, except that it is cited in a large number of exhibitions in major museums. Undoubtedly, thousands have looked at the legendary undrawing. Yet there is next to nothing written about the piece, as if we do not need to bother to look at it. That is exactly the point when I become interested. “Pay no attention to that man behind the curtain”.

There is a physical artifact at the center of this story, and it is on a sheet of paper, housed in a museum. In 1998 Robert Rauschenberg made a gift of several of his most legendary and iconic works to the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, amongst the deposit was his “Erased de Kooning Drawing”. I felt a personal need to examine it up close. I contacted the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, setting an appointment for Wednesday August 29, 2007. Then I got into a car and drove from Colorado, across Utah and Nevada, and a couple days later reached San Francisco.

The artwork was so legendary that had become Grail-like for me. It was not lost, just virtually inaccessible to the point that it may as well have only been a tall tale told by Rauschenberg. Except for inclusion in numerous exhibitions, none of which I had seen, it was in Rauschenberg’s possession for forty-five years. I did not know what to expect. Knowing that it was real, I wanted to stand before it and listen to what it had to say to me. I wished to satisfy my curiosity and at least calculate the cubic centimeters of erasures produced during the defacing of the de Kooning. I wanted to examine the paper and discover what material de Kooning had worked upon. I did not know the size of the paper the drawing was on or the length of linear erasing that might have been involved.

I was welcomed at the museum and taken to see the piece, which was not currently on display, in a curatorial study room. The piece was in a thin gilded wood frame, glazed with plexiglass. Although the artwork was not to be removed from the frame, clearly marked on the back: “DO NOT REMOVE DRAWING FROM FRAME. FRAME IS PART OF DRAWING”, the files were made available to me. I could examine the piece as closely as plexiglass allowed and could look at the reverse indirectly by studying the photos in the file.

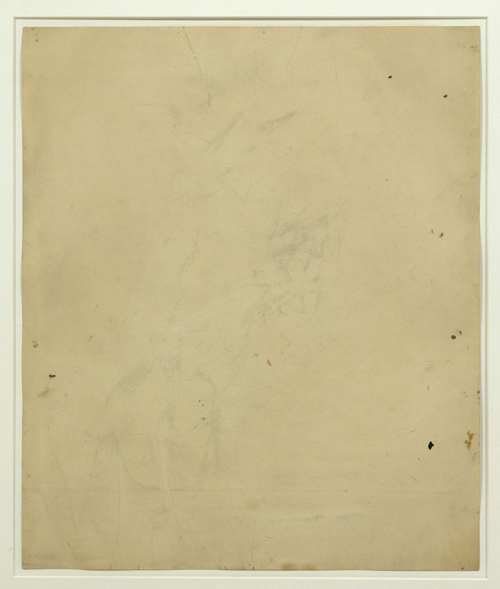

One expects to see a white sheet of paper which has been wiped clean, a complete void, a speckless sheet of paper. Instead one finds a subtle and complex artwork.

The paper is neither fine rag paper nor thin newsprint, but the common, wood pulp type one finds in a student grade sketch book. Such paper is intended for use on both front and back. It is economical and utilitarian paper, not used for serious artworks, but instead for putting ideas into visual note form. All four edges are cut. Three sides are original machine sheared edges. The forth side, on the viewer’s right, is trimmed by hand, either by de Kooning or Rauschenberg. The full page would have included the perforated holes of the spiral binding. The justification for this trimming is that de Kooning likely pulled the page free from a spiral, wire bound notebook. That edge would have been perforated and torn. Rauschenberg would have straightened the edge by cutting before the work was framed and exhibited.

Both sides of the paper are marked upon. The side visible in the frame, is the “erased” side. Although erased, de Kooning’s original images are embedded in the paper, due to the nature of the materials used and are easily viewed, especially in raking light. The marks are all characteristic of de Kooning’s hand. The erased side clearly displays evidence of three partial sketches. Each of these three distinct areas seem to be marked with different media and not at all as easy to erase as pencil. These de Kooning drawings on the recto, erased, front side, remain surprisingly very legible. They consist of a central female figure and two more sketches which do not especially overlap. The central figure, about the size of a closed fist, is an almost complete idea, very similar to his famous paintings of women, especially “Woman I”. I have since viewed more complete drawings that act as studies for “Woman I”. This central figure in the “Erased de Kooning Drawing” helps date the sheet of sketches to the time just prior to Rauschenberg’s date of 1953. This date proves that while de Kooning may not have given a proper finished artwork, he gave one that was recent and contemporary. This small figure should be further compared to the other sketches that de Kooning made as his “Women” evolved. Perhaps a future art historian or curator will consider the Rauschenberg when examining Willem de Kooning’s best known series.

Rauschenberg has taken care to invert this figure, so it is not easily identifiable. In its erased state the female seems to float, head down, on an invisible chair. The other two sets of marks are nondescript and unrelated to each other or the “Woman” study. Together the collection of marks are random and clearly not composed. This sheet is a palimpsest of sorts, although with direct links to de Kooning’s best known work. On neither side is there evidence of ever having been a signature, even an erased one.

When one looks at the framed physical piece, this conceptual relic, one notices colored specks, fingerprints, dabs, and spattered color. These colored specks and stains randomly scattered on the face of the piece are evidence that after the act of erasing the piece was unprotected in the studio environment for probably as long as ten years before it was properly framed and exhibited. Artworks that sit in the studio are prone to receiving unintended, stray paint. This is especially true in the case of Jackson Pollock, whose work is exhibited at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, MoMA, and Centre Pompidou with such extra spatters added after the pieces were signed. During the first ten years the erased drawing may have been temporarily and cheaply framed, which may account for the regularly spaced rust spots on the back, indicating where nails held the artwork into an early frame. These color dabs, splotches, fingerprints, and stains all indicate a life, but should be seen as indeterminate in nature. They animate “Erased de Kooning Drawing” and have become a part of the piece as much as the frame and plexiglass, yet the color spatters are unintentional as fly specks. They are after-the-fact accidental additions.

Let me now return to the legend behind the work.” In an interview published by SFMOMA in Points of Departure and Making Sense of Modern Art, Rauschenberg says; “it took me about a month, and I don’t know how many erasers to do it. But actually, you know, on the other side of this is also, I mean, if there is ever any question about this, this is a gorgeous drawing of Bill’s.”

In Off the Wall, Calvin Tomkins takes all his material directly from Rauschenberg’s mouth in his own interview, so it is the story Rauschenberg clearly wants us to accept. Tomkins does not question the story and says little about the resultant artwork. He stops asking questions when Rauschenberg sums up the action and provides his own climax: “It took me a month and forty erasers, to do it. But in the end it really worked. I liked the result. I felt it was a legitimate work of art, created by the technique of erasing. So the problem was solved, and I didn’t have to do it again.” There you have it. Any questions? Did not think so.

Have you noticed how the number of erasers became more specific?

Tomkins does not make further comment or indicate he has looked at the erased piece. Few writers make mention of the physical object and refer to the same information presented by Tomkins. Jonathon Fineberg, in Art Since 1940, Strategies of Being, adds this commentary:

“He erased for two months but in the end he could not eliminate the lingering presence of de Kooning’s gesture and compositional character”.

Apparently, as the legendary nature of the work grows, so do the length of time spent erasing and the number of erasers consumed. Even the quality of de Kooning’s contribution seems to improve. What I saw as a page torn from a sketchbook, bearing one small, oversized doodle of an angular female figure, with two unrelated, incomplete jottings; is identified as a composition. It is anything but a composition. It is a page with some visual ideas, all unresolved, but worth keeping for reference. One never quite knows when a small scribble of an idea might grow. In looking at published de Kooning drawings, I found no signed drawing made of such unrelated, colliding images. This is a sheet of ideas, not a composed drawing by Willem de Kooning. Rauschenberg has elevated this page of notes to the status of a drawing.. The verso sketch, which he describes as gorgeous, are like the three erased on the other side, not composed, completed, or signed.

If de Kooning did not sacrifice a signed drawing does this devalue the Rauschenberg? Not at all. But it would have risen the stakes had de Kooning committed a finished, signed drawing. Therefore, de Kooning’s contribution demonstrates a lesser commitment to the idea, while still sitting in a position to disclaim the whole thing. He did not contribute an actual drawing.

Could the erasing have taken two months, or weeks and weeks and could Rauschenberg have used forty erasers, as he has been quoted? Perhaps.

Only the art historian Thomas Crow seems to put the brakes on the growing snowball of a legend.

“His notorious act of erasing a drawing solicited from Willem de Kooning in no way obliterated its object; instead, with the faint ghost of the heavy original marks still visible after weeks of labor (and another drawing showing from the opposite side of the sheet), it made it possible for the white paintings and an autograph piece of de Kooning’s art to be apprehended in parallel to one another – the internal contrasts of the latter being diminished to the point that it demanded the same slowed-down, hyper-receptive mode of attention in order to yield up its visual rewards.”

Crow does not count erasers, nor does he speak of laborious duration in more than “weeks”. He does avoid the nature of de Kooning’s marks, but this seems a universal issue among those who have written about the piece. Not one mentions the nature of de Kooning’s “drawing”, only that it is not completely erased. An art historian with a broader knowledge of de Kooning’s imagery would certainly understand where these notes fit into his development in 1951 to 1953. The erased de Kooning is still a de Kooning.

Let us look into Rauschenberg’s use of hyperbole. Why is Rauschenberg quoted as saying he used forty erasers?

When Rauschenberg says he used forty erasers to remove the lines laid down by de Kooning he is claiming to have erased for a time greater than a few minutes and that he wore down more than one eraser to the point when it could no longer be held between his fingers. His authority to spin a version of the truth is as much artifact as the artwork. In such a case as this, the tale takes on much more weight than the physical result displays.

Then again, perhaps it is poetry that Rauschenberg is weaving for us and not a measurement of time and quantity of art materials expended. The story behind the creation of such a legendary artwork is the greater artwork. The tale of the making of the erased drawing is a poetic way of expressing the value of the idea that art may come about in more ways than we may know or expect.

If a long prose poem informs us that the world was created in seven days, why not imagine a drawing erased over the course of decades, taking millions of erasers? Pick a number that pleases you. There is no wrong answer. This is the stuff of legends.

Now for the invisible and forgotten eraser, by which Rauschenberg made a de Kooning his own, perhaps the most poignant element in the act. The implement for removal of de Kooning’s marks would have been the reliable artgum eraser. It is gentle, but reliable, crumbling to nothingness as it fulfills its task of removal. That there are no abrasions of any significance would imply that Rauschenberg artfully erased with an artgum eraser. Such erasing must have produced a pile of art gum fragments, or erasures. Forty unused artgum erasers makes for seventy-two cubic inches of eraser. As an artgum eraser is used the material that breaks away expands to four times its compressed size. If Rauschenberg did use forty erasers, he would have produced 288 cubic inches of erasures.

Rauschenberg tells us that de Kooning gave him something that would be difficult to easily erase. This is perhaps the greatest overlooked component in the story. It is the poetry all artists like to hear and know, that their contributions to art may not be so easily erased or forgotten.

This essay among others is in Sandy Kinnee’s latest book

For more poems & essays by Sandy Kinnee on Arteidolia→