On Russell Atkins

Daniel Barbiero

November 2020

Part 1: One Russell Atkins’ The Poetics of Objectified Mind

The Ontology of the Poem-Object

The poetry of Russell Atkins may not be, as Sartre claimed of Francis Ponge’s poems, on the side of objects, but rather are meant to be objects themselves. To this extent Atkins’ poetry is an ontological poetry—a poetry as much about the poem’s status as a kind of thing as it is about anything else. This in itself may not be remarkable or unique to Atkins—after all, any poem is an object, an artifact made of words which, once made, takes on a life independent of its creator and the fact of its creation. Thus when Atkins states, in the Preface to his 1991 collection Juxtapositions, that his poems are the products of his “object-forming processes at work,” he may seem to be repeating a truism that holds not only for poetry but for any artwork. Consider that through the creative process the artist brings about an opening through which the object—the poem, the painting, the composition and even, arguably, the concept when a physical embodiment is lacking—comes into being, and what Atkins describes is something of a universal constant of creativity. The artist, as object-maker, is the source of the object’s existence (or, to revert to the language of ontology, is the ground of the object’s being). So far, a more or less conventional model of the poem-object as the product of the creative process, whatever this latter may be. Where Atkins puts his own stamp on this model is first of all in his insistence that the poem-object is the projection of a specifically internal process—what elsewhere in his Preface he calls “a kind of objectification of ‘mind’”—and secondly in his assertion that the matter of the object’s “relevance” or ability to communicate or to “mean”—this latter presumably in the sense of having a paraphrasable, indicative content—is simply irrelevant.

A Thing Whose Thingness Is the Material of Language

The ontological claim implied above—that Atkins’ work has a certain mode of being by virtue of its having come into being in a certain way—is worth a quick detour here. It only seems fair to ask, What kind of thing is this poem-object if it comes about through the “objectification of ‘mind?’” That such an objectification culminates in an object can be taken for granted, but what here could be “mind” and what would be its relationship to the resulting object? Casting “mind” in terms of intention or felt experience might get at some aspects of its role vis-à-vis the poem-object, but more fundamental is its standing as the originary event, the nexus and provocation that in two senses stands before the object it gives rise to—by virtue of being both prior to it and outside of, and other to, it as well. “Mind” as the event of the poem-object is mind as the origin or ground that leaves a trace of itself in the poem-object. Mind becomes object through an action on the part of the poet—the opening or “objectification” Atkins speaks of—and relates itself to itself through the object that it is not but that contains its trace and puts it out into the world as something independent of itself. It is itself and not itself, or rather it is itself as that image of itself that is sayable. A material expression, in other words. A kind of thing whose thingness is the material of language, a material into which the event of mind disappears. This material of the poem-object—the language out of which it is constructed—links the intangible event of mind to the physicality of the world. To the extent that the event of mind consists in the extra-linguistic, it may be that something of the event escapes language even as language shapes the expression—literally gives it form—of the event. The possibility that this is a question of fit between two different modalities—mind as such on the one hand, and language on the other—would seem to imply that the fit won’t necessarily be perfect. And by extension that the possibility that at least some residue of mind will elude transposition into language cannot be discounted. But since the focus here is on the poem-object itself this question of the fit, or misfit, between mind and poem-object will have to be a question for another time. Suffice it for now to say that the poem-object is the result of a transformation and transposition—perhaps even a transubstantiation—of the event of mind into the language into which it disappears, even as it leaves traces of itself. Mind, the originary, the event, the disappearance whose material image is its trace, is memorialized in the poem-object.

A Drive Toward Exteriorization

When Atkins speaks of his poetry as consisting in an objectification of mind he is in effect asserting a claim to a poetics of expression, although “expression” is not a word he uses. He prefers the more general term “creativity” to describe his poetics. Nevertheless the process and principles he enunciates in both the Preface and Manifesto (this latter also included in Juxtapositions) make it clear that his creative ethos does assume a form of expression, albeit one with a meaning specific to him. Atkins’ poetic of expression, to the extent that it involves the objectification of mind, would seem to entail the exteriorization into language of the poet’s inner state, however constituted and of whatever content. Which is to say that it consists in an opening out of an internal condition or event that subsequently takes on the object existence of language. (Of course this internal event could also consist in the free play of language within the mind, in which case its taking on the object existence of language is always already accomplished.) The meaning of the poem is thus something like an image of interiority projected outward. (Granted, “interiority” is a term with a metaphysically burdened history, but as a rough metaphor for a mode of being that can only be approached metaphorically, it will have to do.) It is this objectification, or projection, that stands at the heart of Atkins’ artistic practice and that grounds its meaning—this, and not any urge to communicate.

Atkins’ refusal to take communication as the model or goal for poetry is a deliberate element within his poetics; he states as much when he says in the Manifesto that the product of artistic practice “need not communicate” (emphasis in the original). The stereotypical convention regarding communication—that it consists in the transmission of information about things and situations in the surrounding world, and that it can be verified or refuted by a third party on the basis of how things actually are in that world—becomes irrelevant. What is relevant is the poem-object’s having been given rise to as a necessary moment of expression, which Atkins characterizes as its “drive to be brought into existence.” The expressive moment just is enacted in the poem-object’s drive toward exteriorization; its expression is its projection toward being and its reason for being. This reason for being need not be reduced to, or supplemented by, any communicative intention. It is that it simply is.

Idiolect and Association

It might seem that Atkins’ expressionist poetic, in its refusal to communicate, would strand the poem entirely on the side of the interiority that it objectifies. If so, we would seem to be caught in a trap here—a trap of moated interiority, of a pure solipsism enclosed within itself. This would be misleading, though, even if in his Manifesto Atkins licenses the use of solipsism in poetry “if necessary.” For it is precisely in the decision for objectification that the image of interiority runs into a reality outside of itself and molds itself through that reality—the reality of language as always already meaning-laden material. Language as external reality is language as a kind of common property, an accretion of past gestures and future possibilities existing between and transcending any specific instance of use. In being exteriorized into language, the image of interiority is permeated by an external reality characterized by conventions of usage, orthography, definition, and so on. Even when some of those conventions are defied or distorted, as for example with Atkins’ well-known propensity to use an apostrophe rather than the usual “e” as the penultimate character in verbs in the past tense, they make themselves known to us surreptitiously, through the frustrated expectations that their absence or violation precipitates. Appropriated uncommonly, language conventions’ commonality becomes dramatically apparent.

And yet at the same time that language is held in common by a community of users, it also reveals itself to be something different for the different members of that same community. Consider that at a coarse-grained level, different language users’ understandings of a given convention or meaning held in common by the community can be expected to coincide. The finer-grained one gets in explicating a rule of usage or elucidating a meaning, though, the more and greater differences are likely to emerge between users; the more these rules’ and meanings’ peripheries and boundaries are likely to reveal themselves as fuzzy. (This difference between language as common property and language as appropriated by individual users corresponds, roughly, to the difference between on the one hand the structural constants of language, and on the other hand, the contingencies of language as actually internalized and used in specific situations.) In addition to what words mean—that is, the concepts and categories they embody–there is the matter of how they mean for any given user, which is to say the matter of the associations they carry, affective, aesthetic and otherwise, which gives them an extra-semantic or extra-grammatical resonance and which will necessarily be different for different people. Think, for example, of Rimbaud’s assigning to the vowels of the alphabet specific colors and the phenomena that embody them in his sonnet Voyelles. This stands as an example of a systematic—or quasi-systematic—way of bringing to explicit self-awareness a set of linkages that ordinarily operate unthinkingly and on the basis of impressions formed through one’s history of lived experiences. When we consider language at this level it reveals itself to be for individual users an idiolect whose specific meanings and internal relationships are a matter of individual peculiarities based on individual histories and experiences. One may well speak a common tongue, but with one’s own accent.

As it pertains to poetry, the non-semantic, associative linkages permeating language may play a significant role. They may, for example, hold the answers to certain questions such as, Why is this word or this combination of words, or this grammatical construction, put into the poem? If not for their contribution to a referential meaning then perhaps by virtue of the associations they encode individually or in combination, possibly in their sounds or even, in the case of written poetry, their visual appearance or position on the page. All of this may be known only to the poet but that doesn’t preclude these associations from contributing to—or in extreme cases entirely constituting—the poem’s meaning. In fact a poem composed entirely on the basis of idiolectical chains of association may well be an example of the methodological solipsism Atkins’ poetics expressly permits. There is meaning here, but it doesn’t reduce to reference to an external object or situation but rather to how the words are situated within the poet’s network of associations. In a sense this is the most purely expressive, and interior, kind of meaning—one that crystallizes and even dramatizes the idiolectical dimension of language Can such a meaning be communicated? Possibly not, and possibly most likely not. But this lack of communicability is no drawback for a poetry like Atkins,’ which isn’t necessarily grounded in a communicative intent anyway.

Atkins’ poetic seems to demonstrate an intuitive grasp of language as it functions at this level of individual engagement. Consider that with the objectification of the image of interiority there is involved a complex, reciprocal movement: language imposes itself as an exterior material through which the image of interiority must be expressed, but at the same time the image of interiority appropriates language precisely on the basis of the idiolectical networks of affective, aesthetic and other associations that permeate language as the language user knows it. Interiority imposes its own idiolectical nuances on the external material of language, in other words. It may be with something like a sense of language-as-idiolect in mind that Atkins, in his Manifesto, asserts that one should “question ‘the language of common speech’…[and] let poetry thrust toward a language ‘peculiar to itself.’” Exactly how it might do that is a subject Atkins addresses in his Manifesto.

Foregrounding the Aesthetic

The basic principle animating Atkins’ poetics of expression, and hence his methodology, is as fundamental as it is categorical: the poet is the ground of being for the poem-object. As he puts it in the Manifesto, the poet must “be the source of everything” and consequently will set the conditions for the bringing-into-existence of the poem-object. Everything that conditions the poem-object comes from the poet, who should not “risk these conditions for what is called ‘communication.’” Clarity of reference or “sense,” as embodied in the plain voice conveying precisely or economically some item of information, should accordingly be avoided if it risks compromising the expressive force or experimental makeup of the work. Or, as Atkins puts it, “do not destroy a poem trying to make it clear.” In his own poetry, Atkins puts this tenet into practice by pushing to the fore those aspects of the poem that are salient not on the basis of their semantic sense but by virtue of their aesthetic sense.

In order to do this, Atkins advocates techniques or methods geared toward foregrounding the aesthetic or connotative aspects of the poem through a special handling of language. He recommends, for example, that the poet make his or her technique “explicit.” Specific ways of doing this might include using unconventional, non-everyday language rhythms or constructing the poem in a way that will block the reader’s ability to bypass or penetrate the poem’s aesthetic-connotative qualities to get right to the denotative “sense,” if any. One method he recommends for deflecting the search for sense involves a kind of referential conflation through word substitution, in which the poet exploits words’ potential to signify multiple meanings. In concrete terms, using different words to say the same thing—or conversely, using the same words to say different things—by for example repeating or reusing previously used words in different contexts. Beyond the fact that many words do by definition convey multiple meanings, this technique potentially provides an opening in which the idiolectical dimension of language may play a significant role in the poem’s composition. For, if the poet were to put Atkins’ advice into practice he or she might make word choices by distinguishing relationships of similarity and difference not by virtue of reference or dictionary definitions alone, but also—or instead—on the basis of the extra-referential associations words carry within his or her idiolect. (We could even define an idiolect as in part consisting in a differential system based on contrasts of associations—affective, aesthetic, experiential and otherwise extra-referential—specific to the language user, as well as of conventional, interpersonally accessible meanings.) In fact selecting diction on the basis of idiolectical associations rather than dictionary definitions, even in cases where the latter allows multiple meanings to the same word, would be a highly effective way of constituting a poem as a network of significations opaque to any attempt to be deciphered as a plainly referring object. Atkins seems to get at this dimension of linguistic meaning when he says to:

Make use of “implicitness” since a poem is not obligated to avoid inherent meaning similarities…Most grass may be “green” but the word “green” has its own properties.

Not only that, but the properties “green” has can be expected to vary from person to person. My concept of “green” may not be your concept of “green,” hence the word “green” will call up different mental images—perhaps in the form of different shades of green, or different objects that epitomize what “green” is or what it should look like. Through these conceptual and perhaps other kinds of linkages words do have their own properties, and some of these properties, over and above (or “implicit” and below) their commonly held, conventionally defined meanings, are peculiar to the individual language user. If Atkins’ encouragement to the poet to be solipsistic is to draw its force as a practical compositional strategy we could expect to find it here, in the principle that idiolectical associations provide a legitimate ground on which to base a poetics.

Grammar, in the guise of a twisting or alienation of standard grammatical usage, has a role to play here as well. Recall Atkins’ signature gesture of substituting an apostrophe for the omitted “e” before the “d” at the end of a past-tense verb. His reason for doing it, as he explains in the Preface, is to produce a “bold distortion of the weak verb” in order to conflate its functions as adjective and verb. The ambiguity Atkins hopes to create with this simultaneity of function represents a way of using a single word to suggest a branching of grammatical identities and hence to make its direction of reference uncertain. We may not be able to determine easily or even at all what noun the verb/adjective applies to, or whether it applies to any noun present in the text at all. With the possibility of clear referential interpretation blocked, we are offered instead other interpretive possibilities, some of which are driven by aesthetic considerations in which, for example, the word’s rhythm or sound, or appearance on the page, eclipses its semantic sense.

(It might be argued that the deliberate archaism of the elided “e” makes little practical difference here, and that it is instead the shape and makeup of the line or the phrase that does the actual work of confounding interpretation. While there is some merit to this observation, it would seem that Atkins’ unconventional orthographic choice serves to direct attention to the word and to single it out as an interpretive fulcrum on which something of significance balances. Seeing it, the question naturally arises: Why put this archaism here, if not for a reason?)

Disclosing a World

Although in the very first item in his Manifesto Atkins asserts that the artwork “need not communicate,” his poem-objects, simply by virtue of being poem-objects in the first place, do in fact engage the reader in a variety of communication. An artwork qua object is not just any kind of object in a world of objects but is rather a particularly meaningful kind of object. As Gianni Vattimo put it in Art’s Claim to Truth, “the encounter with works of art is never the encounter with another thing in the world; what one encounters is another perspective on the world entering into dialogue with our own” (p. 99). We simply expect to find meaning there. This seems especially true of Atkins’ poetry when considered as a poetry of expression in the sense defined above. In exteriorizing the artist’s interiority (or, in Atkins’ own formulation, “the objectification of ‘mind’”), the poem by its very nature discloses the artist’s engagement with, or attunement to, the world. Such a disclosing object cannot help but be meaningful. The fact that it was created in the first place is an index of its meaningfulness for the artist; that it exists at all as an art object is de facto evidence of the felt necessity that brought it into existence—what Atkins calls “its drive to be”–in such a way that its position cannot be one of indifference, or meaninglessness. Nor can its reception be a matter of indifference. Anyone confronting the art object must come to it with the preunderstanding that it does have meaning, that it does communicate something of the artist’s being in the world, whether or not that meaning can be ascertained easily or even at all. The object is an opening through which the person seeing, hearing, or otherwise coming to it through his or her own way of being can have a meaningful experience of the artist’s way of being. In short Atkins’ poem-objects, by virtue of their having been created, would seem to offer what Vattimo calls a “radically new disclosure on the world.” Atkins may not intend them to communicate necessarily but they nevertheless disclose; they disclose a world of meaningful engagement that constitutes a perspective. They may do so if not through their semantic content, or at least not primarily through their semantic content, then through something else—something as seemingly elusive, yet as fully encompassing and signifying, as the Stimmung or atmosphere they create, through aesthetic means.

*Of course this internal event could also consist in the free play of language within the mind, in which case its taking on the object existence of language is always already accomplished.

Next: On “Exteriors, Interiors”

Works Cited:

Russell Atkins: Juxtapositions (Self-published, 1991).

Gianni Vattimo: “Art, Feeling and Originality in Heidegger’s Aesthetic,” in Art’s Claim to Truth, ed. Santiago Zabala, tr. Luca D’Isanto (NYC: Columbia U Press, 2008).

Read Russell Atkins: Juxtapositions (Self-published, 1991)→

For more information on Russell Atkins

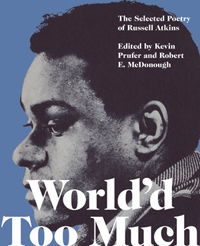

World’d Too Much: The Selected Poetry of Russell Atkins→

◊

Daniel Barbiero is an improvising double bassist who composes graphic scores and writes on music, art and related subjects. He is a regular contributor to Avant Music News and Perfect Sound Forever. His latest releases include Fifteen Miniatures for Prepared Double Bass, Non-places with Cristiano Bocci & their most recent collaboration, Wooden Mirrors.