A Weaponized Art: Hans Haacke

Ron Morosan

December 2019

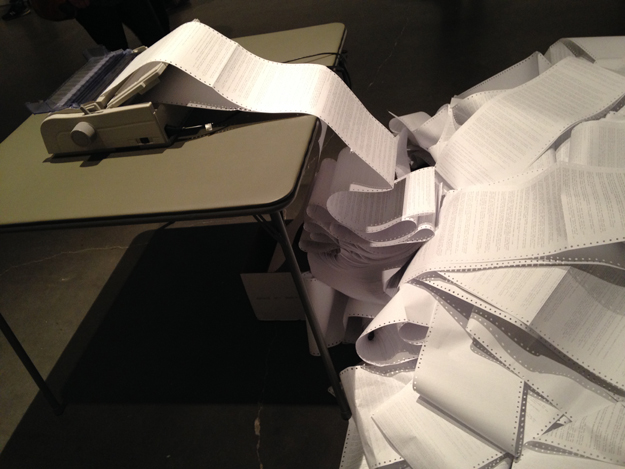

News, 1969/2008, all images courtesy of Arteidolia

News, 1969/2008, all images courtesy of Arteidolia

“In a time of deceit, telling the truth is a revolutionary act.” George Orwell

No doubt, Hans Haacke is a different kind of artist.

Viewed in an art historical and cultural context he would be called a conceptual artist in the vein of Marcel Duchamp. But Haacke is conceptual in a very different way. He takes on corporations, media giants, politicians, and anyone and anything connected with financial power, especially power over people and their art.

All Connected is his second solo exhibition at the New Museum. The first was in 1986 and was titled Unfinished Business. Now with every floor of the museum filled with a retrospective survey of his career we have the sense that the business is complete.

Blue Sail (1964)

Blue Sail (1964)

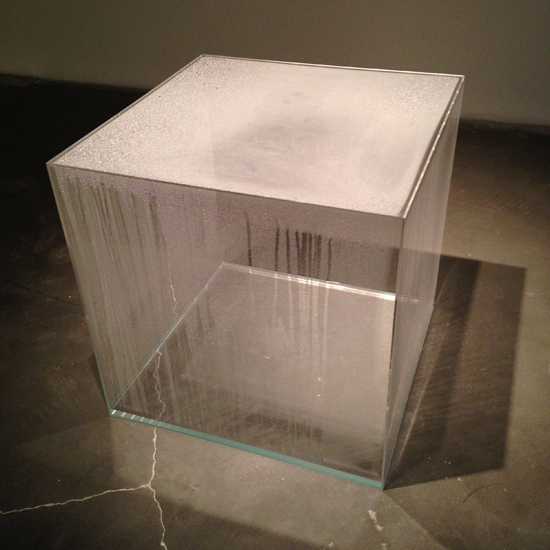

Most of the pieces on display are familiar, but some haven’t been seen for decades—like Condensation Cube (1963-65) and Blue Sail (1964). But this show really displays the full range of Haacke’s political throw-weight, a content that is some of the most high caliber political art made in this country.

During his more than 50-year career he has demonstrated the ability to transform himself into a sequence of incarnations of artist-styled actions; in the 1960’s he was a kinetic systems conceptual artist; in the late 60’s and early 70’s he became an art investigator as, in one example, he expertly unearthed the provenance of Seurat’s painting Les Poseuses, (1975) following it through decades-long changes of hand and increases in price until it became submerged in a murky business of art as commodity.

Earlier, in Shapolsky et al. Manhattan Real Estate Holdings, A Real Time Social System, as of May 1, 1971 he investigates the machinations of a notorious real estate family as he exposed their property purchases, locations, and conditions of their buildings.

In another exhibition titled Gallery Goers’ Birthplace and Residence Profile of 1968-71 he arranged an art viewer focus-group style questionnaire to find out which people go to an art gallery and where they live; he then went to their homes and photographed their buildings.

In all of these art investigations Haacke is gathering and using data. (In a sense he could be an early Facebook pioneer). However, what he does with it is different. Through his research, he is demonstrating how anyone can take on power by using data to expose the dealings going on behind the closed doors of corporations, lawyers offices, media organizations, and real estate companies. Some of his activities might be termed stalking, harassment, prying, or simply nosiness. But with his method, he proposes an empowering of the public, and in that sense he becomes a Robin Hood of data, gathering it from the powerful and giving it to the people.

But Haacke seeks to do more than this: he has larger goals than professional investigative methods. He pursues an ideal of an art-justice in the context of opposing the mega-powers that run the art world, with its museums, billionaire power brokers, corporate sponsors, and media empires.

Taking Stock (unfinished), 1983-84

Taking Stock (unfinished), 1983-84

In his work titled Taking Stock (unfinished) 1983-84, a large painting of British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher, Haacke turned his sites on the machinations of Charles Saatchi and his advertising company Saatchi and Saatchi which he ran with this brother Maurice. Skillfully executed in an ersatz take-off on a royal portrait of the Prime Minister (whose election campaign he ran in 1979,1983 and 1987) complete with gilded frame, the painting is loaded with visual clues to the shadowy deals Charles made with the Tate Museum, the Whitechapel art gallery and Christie’s auction house and the Sensations Show that promoted a group of young British artists who were in the the collection of Charles. When Taking Stock ( unfinished ) was exhibited at the Tate, Charles resigned from the Whitechapel Art Gallery board and from the Patrons of New Art at the Tate.

In an even bigger target, Haacke attacks capitalism itself as a rapacious economic system that can only function by control and command over any endeavor it undertakes to exploit. Most of his work exposes the wholesale takeover of the cultural context itself.

In Culture, Inc., a book by Herbert Schiller, Haacke is described as an artist who tries to unveil the vast consciousness industry that has enveloped the cultural sphere in New York cultural institutions and European art centers. Schiller writes: “What he has been about has been nothing less than stripping bare the consciousness industry itself and the place of art and the museums as components of that industry.”

What is the consciousness industry? Although most Americans are not familiar with this term, it is, in fact, one of the dominant forces shaping their behavior. The consciousness industry is the conglomerate of corporate media, advertising, cultural image, and consumer demographics that essentially influence what the public will think about. And it does this on a huge national scale.

In its more familiar guise the term is public relations.This brainchild of Edward Bernays, nephew of Sigmund Freud and guru of Madison Avenue, it attempts to shape and influence what the public will think about a particular product or service and if they will buy it.

During the 60’s and early 70’s public relations discovered the fine arts. It was partly due to the success of Pop Art, and the global success of American art in general. Advertising companies recognized this and sold their services to corporations seeking to use art to enhance their image.

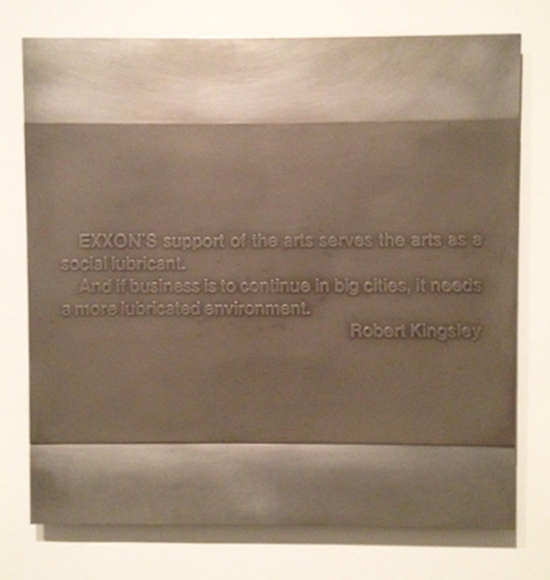

On Social Grease, 1975

On Social Grease, 1975

Haacke’s exposé of one of the best schemes to use the arts is: On Social Grease. This amusing title is taken from the actual words of an Exxon executive Robert Kingsley who was then chairman of an arts and business council. As Kingsley writes: “Exxon’s support of the arts serves as a social lubricant. And if business is to continue in big cities, it needs a lubricated environment.” This exhibition consisted of six plaques of photoengraved magnesium plates mounted on aluminum that reproduce statements on the utility of the arts to business. In another plaque David Rockefeller is more specific: “From an economic standpoint such involvements in the arts can mean direct and tangible benefits. It can provide a company with extensive publicity and advertising, a brighter public reputation and an improved corporate image.”

Born in Germany in 1936, Haacke grew up during the war and contended with life in the bombed-out city of Cologne. This tragic context would have certainly influenced him to look at the dark side of human behavior. In many ways his view of the power structures of American capitalism give his personal approach to confronting power a style that might suggest the melancholy in Shakespeare’s Hamlet, when the guard Marcellus remarks,“Something is rotten in the state of Denmark.”

In much of Haacke’s work he uses a term called “real time systems.” The concept of system design or the application of systemic rational networks is cutting edge technology today. It provides a platform for audience participation on an immediate level, making the audience participants. In this sense he was again ahead of his time in viewing the audience or the public as a system. Now this view is standard policy in any media seeking to involve an audience in an interactive real time program.

However, reason and its systems can go awry as is illustrated in Goya’s etching from Los Caprichos: “The sleep of reason can produce monsters.” Examples are the fable of the Sorcerer’s Apprentice, or even the highway systems of the USA, which all become trapped in entropy. But, as Haacke uses systems thinking he employs it as a social weapon. This has produced the trend of institutional critique in which individual artists or artists’ groups attack museums for not acknowledging their particular grievance, which may vary from being elitist, or to not being inclusive; or, as Haacke has done, lending their image and exhibitions to corporations for image enhancement.

MetroMobilation, 1985

MetroMobilation, 1985

MetroMobilation from 1985 is one of Haacke’s largest and most ironic installations, in which he creates a theatre-like satire of Mobile Oil sponsorship of an exhibition of ancient Nigerian sculpture. At the same time, Mobile Oil was also providing oil and services to the Apartheid government of South Africa. The installation mocks the facade of the Metropolitan Museum with three banners that reflect the customary exhibition announcement for what is on display inside. These hang over photographs of African people marching as prisoners. On the upper cornice is a centrally located plaque with the words used in a promotional leaflet accompanying the exhibition: “Many public relations opportunities are available through the sponsorship of programs, special exhibitions and services. These can often provide a creative and cost-effective answer to a specific marketing objective, particularly where international, governmental, or consumer relations may be a fundamental concern.” In viewing MetroMobilization one might find oneself smiling at the humor produced by the irony of such a construction; while it criticizes the patronage of the exhibition by a corporation that turns its back on racial injustice, the triumph of capitalism is also being challenged. No doubt the “power elite” throughout history have been patrons of art. There is no way this is going away. But is taking an ironic position in relation to power, to critique and create conflict in the cultural institution a way to change it? That is still an open question in Haacke’s work.

Condensation Cube (1963-65)

Condensation Cube (1963-65)

The larger issue that surrounds all of Haacke’s institutional critiques is the concept of the tragic. We live in a capitalist culture and the only weapon we have to protest the exploitation of art is to create monuments and actions to condemn, criticize, protest, and yell at the power that controls our lives and the art we make. This is the tragic side of the triumph of the capitalist system, the biggest and most successful system in history.

As the British socio-cultural writer Mark Fisher wrote in the first chapter of his book Capitalist Realism, is there no alternative? He said, “It’s easier to imagine the end of the world than the end of capitalism.” A sobering and scary thought.

Gift Horse (2014)

Gift Horse (2014)

The centerpiece of Haacke’s show and probably his masterpiece, if we must choose one, is Gift Horse (2014), the monumental bronze skeleton of a horse set high up on a plinth, as it was commissioned to be sited in London’s Trafalgar Square. This ghostly and horrifying oversized skeleton is wearing on it’s raised left front leg a ribbon of real time stock quotes from the wall street stock exchange. What is the irony here? What would a Goldman Sachs partner think of it? The interpretation can go at least two ways. Either the capitalist would like it, saying this is proof that we use-up the world and are as powerful as death itself. Or, it could say that capitalism is eventually going to destroy the world. Gift Horse owes its title to the Trojan Horse of the ancient Greek Homeric tale—But Gift Horse could also be electronic technology and artificial Intelligence. One way or the other this work is about the tragedy of human life today and the darkness that seems to loom ahead.

As a data warrior Hans Haacke could be compared to Julian Assange. He, too, was using data to perform a public disclosure mission of uncovering the dark side of financial machinations and the privilege of power and money. However, Assange is in jail. Luckily for Haacke he has the institutions of art museums, and the art world to protect him from the power elite.

Hans Haacke: All Connected→

New Museum, New York City

October 24 – January 26, 2020

Ron Morosan is an artist, writer, and curator. He has shown his work internationally at the American Pavilion of The Venice Biennale and the Circulo De Bellas Artes in Madrid, Spain. In the US he has shown at the New Museum and had a one-person exhibition at the New Jersey State Museum, and at numerous galleries in New York. He curated the Robert Dowd exhibition, Subversive Pop, at Center Galleries in Detroit, as well as Denotation, Connotation, Implication at Eisner Gallery, City University of New York. He has written catalogues for many artists, including Enid Sanford, Tom Parish, Robert Dowd, and others. In the 1990’s he started and ran B4A Gallery in Soho, New York, writing press releases, articles, and catalogues.