Picabia: “I am a Dada Monster”

Ron Morosan

March 2017

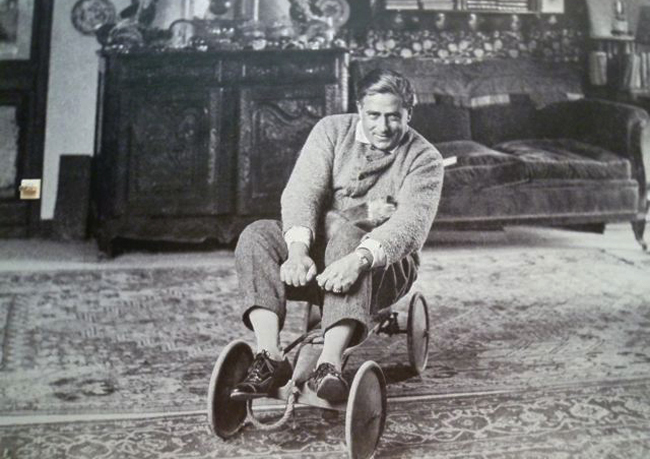

Greeting viewers entering the Picabia exhibition at MoMA is an enormous floor-to-ceiling wall photograph showing Picabia sitting in a child’s wagon. He looks like a big baby. Are the curators making a suggestion that maybe Picabia was a big baby and that is why he “couldn’t sit still” and be a normal avant garde artist? Instead, he was wild, unruly, all-over-the-place, and very difficult to categorize.

In viewing this intense and innovative retrospective of paintings, letters, and printed works, the first in almost fifty years, I was stunned by Picabia’s peculiar inventive spirit. He was a monster of inventive art. He seems to have been intoxicated by the avant garde idea. He realized that art was a medium, both visual and intellectual, rational and absurd, through which new concepts could be created, and there were new ways of working that were completely open: all was possible. He leaped into this ocean of possibility headfirst and swam like crazy.

Starting from a solid training in Impressionism, he developed his own self-styled Cubism and took this concept to the maximum in large ambitious paintings like Edtaonisl and Udnie. Though meeting with disregard by critics who called them “incomprehensible heaps of red and black shavings,” his inclusion in New York’s 1913 Armory show garnered him an audience in the United States.

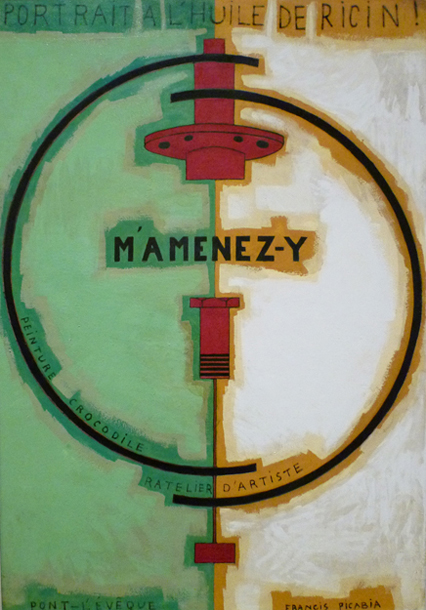

MAMENZ-Y, image courtesy of the author

MAMENZ-Y, image courtesy of the author

This encouragement propelled him to develop new works that re-conceptualized machine mechanisms into absurd pseudo-sexual contraptions. In the series titled Mechanomorphs, the painting Bring Me There of 1919-1920 presents a good example of how he was influenced by the Dadaist fixation on the machine as a sexual subject, suggesting a contest of power between male and female in a metaphor of a sadomasochistic distortion of love. (In this group of works we see ample evidence of how much he was influenced by Marcel Duchamp who took the machine mythology to much greater ends in his Large Glass.)

Meeting Marcel Duchamp in 1911, Picabia maintained close contact with him and the circle of Dadaists in Europe and New York. In many ways Picabia became a principle of the Dada movement by publishing the Dada journal 391. Then he published and illustrated numerous journals that provided literary and artistic outlets for Dada art and ideas. Dada’s equivocation of intent permeates all of Picabia’s work which contains a sense of irony, while at the same time hovering at the edge of comprehension. The irrational and nonsensical is the underlying message of Dada and this is present in all of his paintings of this period.

But Picabia was art-invention crazy, and he had to try everything. He even engaged in collective art making when he invited visiting friends to add writing or drawings to his collage painting The Cacodylic Eye of 1921. The result is one of the earliest examples of graffiti art and a peculiar form of graphic party theatre, similar in format to the Surrealist Cadavre Exquis.

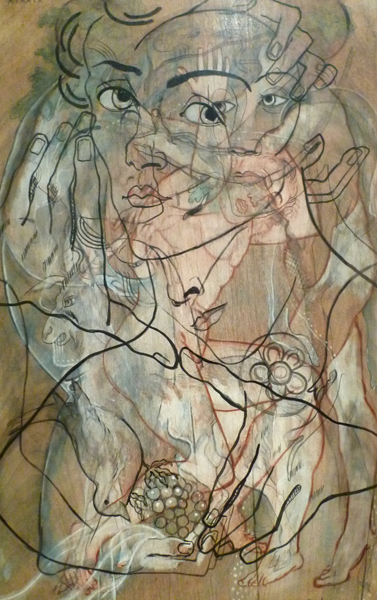

La Nuit Espagnole, image courtesy of the author

La Nuit Espagnole, image courtesy of the author

Going through MoMA’s exhibition is like transitioning through a laboratory of art ideas: Picabia displays an almost scientific approach to art making. Work of the early 1920’s like The Spanish Night of 1922 suggests a plotted-out black and white enigma of romance and science. Dots of white and black on the surface of the clothed male and naked female figures indicate a kind of system connecting the dots, and invite us into a game; the two targets in the breast and torso of the female indicate areas of male attraction, where we are led to think of seduction, possibly a one night stand, or some primal enigma of male and female sexuality.

His collaboration with Rene Clair produced the film Entr’ Acte, a masterpiece of film as medium and probably one of the most influential films ever made. It engages in innovation and inventiveness to an extreme, with cinematic magic disappearance, an extraordinary chase, extreme camera angles, and charm in stagecraft that is sure to delight everyone.

Then we come to his Transparencies Series, a group of works that became one of his signatures styles. In this series of paintings he draws with paint, image upon image, superimposing faces upon faces, bodies upon bodies, and numerous other images that challenge our eye to make out all that is there. In fact we are frustrated in seeing everything simultaneously. He achieves a montage on a two dimensional surface, and introduces an experience that is close to film. In a painting like Atrata of 1929 there is a feeling of vertigo produced as we view a large face of a woman that is swimming in numerous dizzying images, seeming to overwhelm us as in a dream. With Picabia the saying, “Too much is not enough.” would apply.

Arata, image courtesy of the author

Arata, image courtesy of the author

Many art historians and critics have a hard time placing Picabia in the art historical narrative. Dadaist, Absurdist, provocateur, bon vivant, eccentric, Picabia was all of these, but he also seemed to be in a category all his own: an artist as a living laboratory of experimental ideas. There is always a sense of studied determinism to his work; he distinctly sets out on a path, pursuing wherever his eye and mind lead him. But, his method could be abrupt and without the transitional works that show development.

Then there are the Kitsch paintings of the 1940‘s. For many years the art intelligentsia wanted to forget about these works. They were described as Picabia’s mistake. Everything seemed wrong about them. They were painted during WWII, when Picabia was safely ensconced in a villa in the south of France. The content of the paintings, often taken form post-cards of soft core pornography, seemed offensive, and some people even thought the works were pro-Nazi realism.

Spring, image courtesy of the author

Spring, image courtesy of the author

Now this body of paintings is heralded as the precursor of Postmodern social media satire. Contemporary artists are influenced by these works and view them as allowing freedom to pursue what came be called “Bad Painting.” Marcia Tucker curated a show with this title for the New Museum in 1978 in which kitsch was viewed as a genre of underground rebellion to the mainstream art world. Thank you, Picabia!

A question keeps arising: why does Picabia’s work look so contemporary?

A possible answer may lie in his involvement with illustration and film. It is clear in his publishing enterprises that he took illustration and the narrative very seriously. A large number of his paintings have written sentences in them, and every effort was made in planning the covers of his journals, including Literature and 391. It is inviting to speculate that perhaps Picabia viewed his life as a movie. In this filmic context change of subject in his paintings would be more like changes of scene in a film, a quality that has come to be a large part of our contemporary experience. Everyone would understand you if you said, “I feel like my life is a movie.”

By the 1950’s Picabia proclaimed, “figurative painting was dead” and he embarked on a group of abstract paintings that were not entirely abstract. They were symbolic organic forms that conveyed a weird science, with odd squares taking positions on the canvas that might be plots for personal rituals, or formulas for enigmatic visual games.

Prescient pioneer, enigmatic irascible, brilliant innovator, Picabia will continue to influence future art. Today, it is not an exaggeration to say that everyone is painting in one way or another like him.

Francis Picabia:

Our Heads are Round so Our Thoughts Can Change Directions

Museum of Modern Art

through March 19, 2017