The Gospel According to Women Photographers

Carrie Crow

May 2016

Eva, Anna, Margrethe, Doris:

The Gospel According to Women Photographers

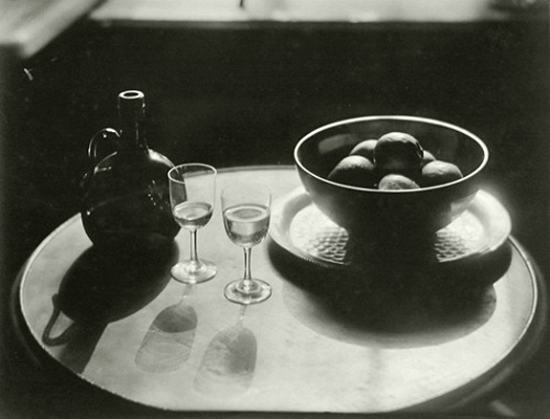

Study in Circles, 1923 – Margaret Watkins

Study in Circles, 1923 – Margaret Watkins

The woman who makes photography profitable must have, as to personal qualities, good common sense, unlimited patience to carry her through endless failures, equally unlimited tact, good taste, a quick eye, a talent for detail, and a genius for hard work. – Frances Benjamin Johnston

Since the publication of “Women Were Photography Pioneers Too, Part One,” I’ve been thinking about why it is exactly that most women photographers have had their work relegated to mere footnotes in the history of photography narrative. It perplexes me, considering that half of the women discussed in Part One were working alongside or were even founding members of the same photography movements as men, and their work at the time was indisputably considered on par.

At first I considered that perhaps these women’s personal stories were at fault. We are a society that loves the myth of the tortured artist and nowhere is that more apparent than on museum walls. We memorize and retell the sordid details of the tragic artistic life, from Van Gogh’s ear to Mark Rothko’s suicide to Jackson Pollock’s car crash, and it seems to me sometimes the more infamous the story, the more famous the artist.

Broadly speaking, however, photographers don’t tend to be a scandalous bunch. Of course there are troubled souls in the mix and more than one photographer—especially conflict photojournalists—has met a tragic end. Photographers, by nature, tend to skew on the bookish side perhaps owing to their craft being a distinct balance of science and art. Photography doesn’t tend to attract those in search of a means for tormented self-expression therefore, with rare exceptions (Diane Arbus and Francesca Woodman come to mind), few men and women have gained status in history under the myth of ‘the tortured photographer.’

A few weeks ago, in answering interview questions by email, I made a disturbing realization. Responding to a question about which photographers I admire, without a moment’s hesitation I wrote: André Kertész and Brassaï (for mood), Man Ray (experimentation), Robert Capa (empathy), Henri Cartier-Bresson (timing), Harry Callahan (line). I had the list typed out before I realized that in spite of having dedicated the preceding three months researching brilliant but often forgotten 19th and 20th century women photographers, in a roundup of photographers I admired, I hadn’t named a single one.

That’s when it hit me: the repetition is the rub.

It’s not only the scandalous stories we repeat, it’s the names. We repeat the names of the brilliant men of history Gospel-like while failing to name the women: Matthew, Mark, Luke, John. Harry, Henri, André, Man. Never Eva, Anna, Margrethe, Doris. It was a sad moment to discover that despite my deep admiration for these women, their names never even crossed my mind.

Recognizing that it takes consciousness and repetition to establish a more balanced view of the pioneering photographers in history regardless of gender, I amended my interview answer. Not for unwarranted affirmative action, but because it is true. Ask me again which photographers I admire and my answer will be: André Kertész, Brassaï, Lady Clementina Hawarden (for mood), Man Ray, Margrethe Mather (experimentation), Robert Capa, Doris Ullmann (empathy), Henri Cartier-Bresson, Eva Watson-Schütze (timing), Harry Callahan and Anna Atkins (line).

It takes practice. It’s not too late.

Women Were Photography Pioneers Too

Part Two

Christina Broom (1862-1939)

A sentinel in the midst of chaos, Christina Broom appeared to thrive in complex photographic situations making her an invaluable resource in documenting the women’s suffrage movement with her dignified group portraits. Despite the bulk and weight of the equipment of the time which would have inhibited movement, Broom was skilled at arranging many subjects within a frame, making them appear both poised and lively. Credited with being the UK’s first female photojournalist, Broom was a widow by the age of 50 and carried on a successful business selling postcards of her work with her daughter who also acted as her darkroom assistant.

Nurses and midwives marching in Pageant of Women’s Trades and Professions, 1909

Nurses and midwives marching in Pageant of Women’s Trades and Professions, 1909

Frances “Fannie” Benjamin Johnston (1864-1952)

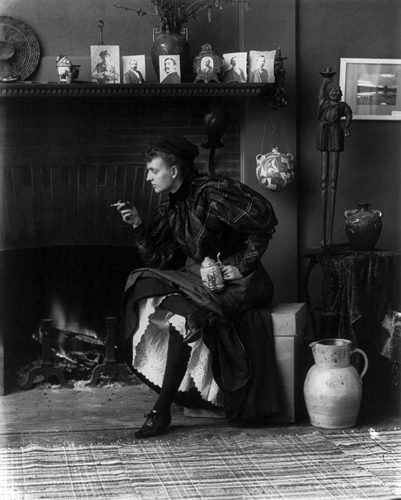

When I look at Fannie Benjamin Johnston’s 1896 self-portrait with her skirt hiked and beer stein and cigarette in hand, I see an Annie Leibovitz portrait 100 years before its time, so fueled is her composition with energy and modernity. As progressive in her treatment of documentary subjects as she was in portraiture, Johnston was one of the first female photojournalists in America, regarded for her architectural series of cities falling into disrepair a century before “ruin porn” was a thing. Liberal, openly gay and fiercely self-reliant, Johnston was an advocate for women’s independence, encouraging them to pursue photography as a means for supporting themselves.

Frances Benjamin Johnston, self-portrait, 1896

Frances Benjamin Johnston, self-portrait, 1896

Alice Boughton (1866 –1943)

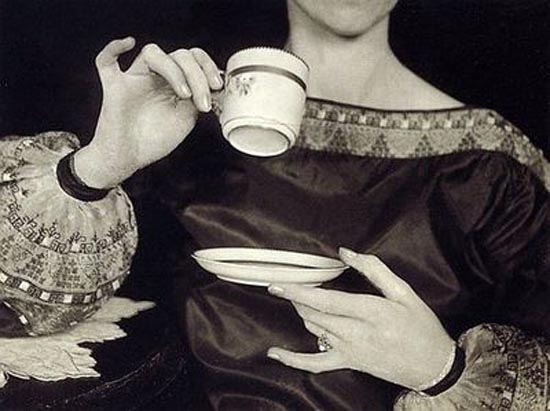

A Photo-Secessionist and leading celebrity photographer whose portrait of Robert Louis Stevenson was a direct model for John Singer Sargent’s painting of the writer, Boughton honed her craft as Gertrude Käsebier’s studio assistant and studied painting in Paris and Rome. It is her portrait of French chanteuse Yvette Gilbert that stands out as an example of Boughton’s lyricism as a portrait artist; her work is notable for her mastery of elegant lines and languid, sensual poses. Like many women photographers of the time, she had a longtime companionship with another woman and made her living from her photographic work.

Yvette Gilbert, date unknown

Yvette Gilbert, date unknown

Lily Edith White (1866-1944)

As a “lady member” of the Oregon Camera Club, White enjoyed a 50% discount on her annual membership dues and was quickly elevated to the role of instructor due to her mastery of the medium and superior work. White outfitted an 80-foot houseboat with a darkroom and along with fellow Oregonian photographer Sarah Ladd, led photographic excursions on the Columbia River, once avoiding potential disaster by fixing a motor with her own hairpin. Her unfettered access to the river allowed her to capture images at any time, resulting in unusually sensitive landscapes sometimes illuminated by the light of the moon. Having advanced far beyond the “amateur” status of local camera club members, White and Ladd gained the respect and admiration of Alfred Stieglitz and were honored with international exhibitions of their work.

Castle Rock and Houseboat, 1902

Castle Rock and Houseboat, 1902

Anne Brigman (1869-1950)

At a time when most pictorialist photographers were constructing painterly landscapes, city scenes and formal portraiture, Brigman was hauling photographic equipment and camping gear high up in the Sierra Nevada mountains for weeks-long experimentations with environmental nude self-portraits that even today feel avant-garde. After seeing Stieglitz’s work in his seminal publication Camera Work, Brigman wrote him a letter of admiration which in turn led to an invitation to join the Photo-Secession movement as a Fellow, the only photographer on the west coast to be so honored.

Storm Tree, 1915

Storm Tree, 1915

Zaida Ben-Yúsuf (1869-1933)

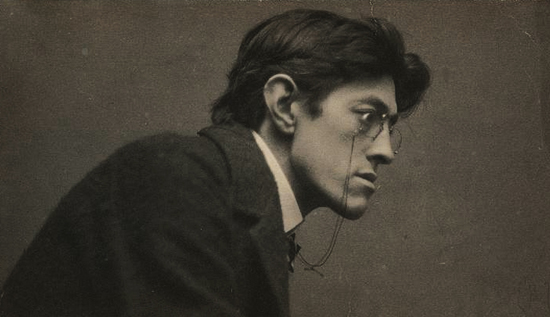

In the early 1900s, Ben-Yúsuf operated the most popular portrait studio in New York City photographing everyone from Theodore Roosevelt to Grover Cleveland to Edith Wharton, remarkable company for a relatively young émigré from London. Celebrated for her artistic, rather than purely commercial portraiture, Ben-Yúsuf epitomized the “New Woman”, a term attributed to turn of the century women who rejected traditional gender roles and sought independence. A milliner as well as a portrait artist, Ben-Yúsuf penned such articles as “The Making and Trimming of a Hat” for Ladies’ Home Journal, which three years later would feature her as one of “The Foremost Women Photographers in America,” a testament to the lengths at which women had to hustle to support themselves. Ben-Yúsuf teamed up with Frances Benjamin Johnston to co-curate an exhibition of emerging American women photographers at the Universal Exposition in Paris in 1900.

Portrait of Sadakichi Hartmann, 1899

Portrait of Sadakichi Hartmann, 1899

Jessie Tarbox Beals (1870-1942)

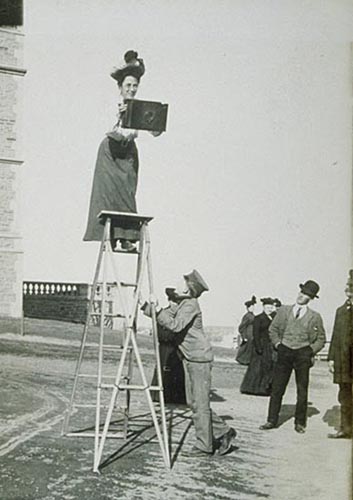

There is a frankness in Jessie Tarbox Beals’ photojournalism that is admirable. Neither overly composed nor perfectly framed, one gets the sense in looking at her images that it was enough for her to simply be there and photograph what she saw without pretense or artifice. Attributed with being the first female night photographer and first by-lined female photojournalist, Jessie Tarbox Beals received her first photo credit in the Windham County Reformer in 1900. Hardly looking it in head-to-toe Victorian garb, Tarbox Beals was a hustler and a daredevil, breaking rank with fellow photojournalists and climbing on top of furniture and ladders to get her shot at any cost.

Physically Defective Children, Parkinson’s Disease, 1910

Physically Defective Children, Parkinson’s Disease, 1910

Margaret Watkins (1884–1969)

For nearly half a century, Margaret Watkins lived in obscurity in Glasgow, never disclosing to friends and neighbors that she was one of the first art photographers (and certainly one of the first women) in advertising, a teacher at the renowned Clarence White School of Photography in Boston where she mentored Margaret Bourke-White, Doris Ullmann, and many others, and was one of the first photographers to shift away from pictorialism in favor of modernism. Her unusually cropped images and elevation of domestic objects into items of artistic value demonstrate Watkins’ experimental nature and early incorporation of surrealism in her work.

Verna Skelton Posing for Cutex Advertisement, 1924

Verna Skelton Posing for Cutex Advertisement, 1924

Laura Gilpin (1891-1979)

One of many aspiring women photographers mentored by Gertrude Käsebier, Gilpin was one of the later devotees of pictorialism, creating evocative landscapes of the American Southwest and portraits of its Native people. Gilpin showed a particular sensitivity to the impact of humanity on nature and often included a lone figure in her landscapes, a unique attribute at a time when for most American landscape photographers, nature alone was king. Like many of the women photographers in this series, Gilpin moved fluidly between styles and subjects finding an original way to work in sharper focused imagery when pictorialism fell out of favor. She supported herself as a photographer for over half a century.

At the Edge of the Plains, 1923

At the Edge of the Plains, 1923

Yevonde Cumbers Middleton (1893-1975)

While the majority of people on both sides of the Atlantic looked at color photography with utter contempt, Madame Yevonde was in the midst of an explosively creative period with the process, developing her signature style and mastering her technique. Despite a climate of hostility toward the “unnatural” look of color portraiture (polite British society thought it vulgar), Madame Yevonde, undeterred, mounted her own solo exhibition in London, the first such exhibition of color portraits by any photographer in England and became a sought after portrait artist for England’s elite.

Lady Milbanke as Penthelisa, Queen of the Amazons, 1935

Lady Milbanke as Penthelisa, Queen of the Amazons, 1935

Despite extraordinary odds against them making an independent living out of photography let alone forging new ground in the medium, most of the women in this series fell into obscurity in later life, entirely forgotten for their photographic achievements. Alice Boughton threw away most of her body of work before leaving New York City for Long Island, Margaret Watkins gave her oeuvre to an unsuspecting neighbor before her death and Zaida Ben-Yusuf was repeatedly listed in the New York Times as a debtor, which must have been humiliating for someone once so admired by the New York elite. In spite of this, with photography becoming ever more accessible by the early 20th century, a new group of women brought exciting innovations to the medium of photography. We’ll look at them in Part Three of this series.

Jessie Tarbox Beals at work, 1904

Jessie Tarbox Beals at work, 1904

Women Were Photography Pioneers Too Series links:

Where Are All The Great Grandmothers of Photography?

Part One – April 2016

What We Talk About When We Talk About Women Photographers

On Helping and Hindering Their Legacy

Part Three – June 2016

You left out Claude Cahun.