Ted Joans: Jazz Was His Religion

Olivier Ledure

January 2018

Image from cover of Afrodisia : Old and New Poems

Image from cover of Afrodisia : Old and New Poems

Honestly, I don’t remember precisely why I decided to write this article. Several events could explain what led me to do this project.

Let me present “me, myself and I” (one of Ted Joans’ favorite expressions). Since 2005, in my spare time, I have been writing about South African jazz for Improjazz, a French jazz magazine. My first jazz concert experience was in Paris in 1976, seeing a duo of Archie Shepp and Max Roach organized by Gerard Terrones. I have always loved poetry since I was young, and just the year before that, thanks to my French professor, I had discovered surrealism through one of Paul Eluard’s poems: La Terre Est Bleue Comme Une Orange. Once my studies were over, I left for Ivory Coast for three years and visited South Africa five times. Shepp, Surrealism and Africa paved the way for my future involvement with Ted Joans.

I started to collect his books and recordings. I met several friends of THE Jazzpoet who had known him in Paris. Among them was the excellent Jazz photographer Thierry Trombert who knew Ted Joans well & documented him in his photography. It was with the total confidence of Philippe Renaud (editor of Improjazz), and through my experience of seeing Ted Joans reciting “Jazz Is My Religion” in the 1964 Amsterdam film clip, that I finally began to write this article devoted to Theodore Jones, alias Ted Joans, with whom I have had a long relationship without ever having met him. The article was published in Improjazz 2015.

Around the same time, on the other side of the Atlantic Ocean, Yuko Otomo was writing the first part of her Ted Joans tribute, Let’s Get TEDucated! that was published by Arteidolia in June 2015. She published the second part, A Tribute to Ted Joans in March 2017. I agree with her that this great Jazz poet deserves much more serious attention. So, I decided to undertake the article’s translation into English, adding some new materials (books, magazines and collages), with Lynn Maillardet as translator.

Ted Joans: Jazz Was His Religion

THEODORE JONES, alias TED JOANS

JAZZ POET, MUSICIAN,

PAINTER and CARTOONIST

![]()

4th July 1928 – 25th April 2003

Jazz is my religion and Surrealism is my point of view written by Ted Joans resumes him well, but we shall see that these are not his only artistic dimensions.Passing away two months before his 75th birthday Ted Joans had lived several lives:

He was born in 1928 on American Independence Day, on a boat where his father was an entertainer, and had lived in several towns, notably New York during 10 years, between 1951 and 1960.

He exiled himself to Europe, particularly to Paris where he resided for quite some time.

In parallel he travelled in Africa, his point of attachment being Mali where he kept a house at Timbuktu, more or less up to his death.

He also travelled occasionally in Central America, and Mexico was not unknown to him.

He died in Canada.

As a teenager his first emotions as a young reader were surrealist, then upon his arrival in France he wrote to André Breton, who opened wide the doors to his movement. Previously Ted Joans had also invested in the Beat movement: amongst others he knew Jack Kerouac in New York and he frequented the famous Beat Hotel, situated at 9, rue Gît-le Cœur in Paris with William Burroughs and Allen Ginsberg.

In music Ted Joans was rarely mistaken, he admired and knew (some very closely) all the greatest jazzmen, from Louis Armstrong to Albert Ayler, Duke Ellington to John Coltrane, Charlie Parker to Archie Shepp, in passing Charlie Mingus. He had in some way crossed the whole history of jazz.

But Ted Joans was one of the first Jazz Poets after the most important promoter of the Harlem Renaissance, Langston Hughes, 30 years his elder. It was in this gender that he excelled: his jazzastic slams, we say today, opened up the way for The Last Poets and Gil Scott-Heron in the 70’s and Saul Williams from 2000.

Let’s take a closer look at some of the most striking episodes in his life

So, it’s on July 4th, 1928 that Theodore Jones saw the light of day, on a boat, where his parents worked. From his birth the passion of travel would inhabit him.

You will have noticed that, if Ted is the diminutive of Theodore, he changed his name from Jones to Joans. This change was said to have intervened following one of his many marriages, one of which was to a woman called Joan.

In an article for Jazz Hot, he said he had started to play the flugelhorn at five, but it seems more likely at 12 or 13, as he later told other journalists.

Around the age of 14, his aunt, who worked as a domestic for intellectuals returned from Europe, bringing him surrealist books, this was a revelation: he literally fell into this movement, as I did 40 years later.

In 1951 at 23, newly graduated in Fine Arts from the University of Indiana, Ted Joans left for New York to continue his studies. It was in this town that he made his most important musical encounters, Miles Davis, Dizzy Gillespie, Thelonious Monk, Fats Navarro and above all Charlie Parker. The bop revolution was in full swing, he was at the forefront !

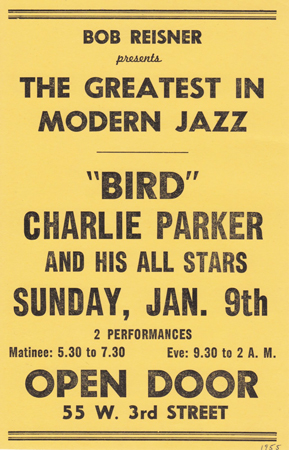

One of the last appearances of

One of the last appearances of

Bird at the Open Door, January 9th 1955

He was even one of the actors: in 1954, Ted Joans had organized a dada-surreal party and Charlie Parker was one of the guests! A famous photograph of Bird, taken by Arthur Fellig, better known under the pseudonym of Weegee, showed him disguised as Mau Mau. This evening also saw a lecture of André Breton and Benjamin Péret’s poems.

I found five photographs of this evening: three in Weegee The Village Da Capo (USA 1989). This book without page numbers and captions was published some 20 years after the death of the photographer in 1968. Another two in Jazz Magazine #216 from November 1973 (p44). These two pictures are credited to a mysterious a.a.a.a.a.

In Weegee’s pictures Ted Joans is wearing a white garment, on which is marked his name, his face is divided in two: one side white, the other not painted. Charlie Parker is the only person crouching in the group picture. I’m not allowed to publish this picture, only if I’m ready to pay an unreasonable amount of money.

On a Turkish website I found one of the copies of Bird’s Lives !, a graffiti by Ted Joans (or one of his friends who accompanied him) with which he covered the walls of New York the day after Charlie Parker’s death.

Inscription Bird Lives ! by Ted Joans or one of his friends

Inscription Bird Lives ! by Ted Joans or one of his friends

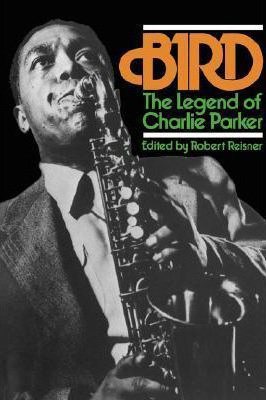

The book written in 1962 by Robert George Reisner, BIRD: The Legend of Charlie Parker goes over the evening organized by Ted Joans, (during one of the 81 interviews conducted by Bob Reisner) who was in fact the manager of a club, The Open Door, where Charlie Parker played many times, as you can see by the poster.

Bird: The legend of Charlie Parker

Bird: The legend of Charlie Parker

Ted Joans wrote 3 pages (p116-118) in the book Bird: The Book of Charlie Parker. He goes back to his dada-surreal party and publishes a poem I Love a Big Big Bird.

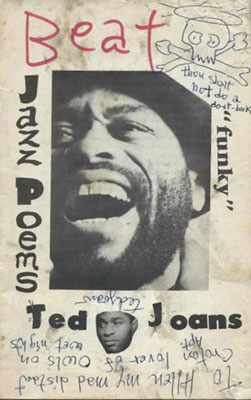

In 1959 Rhino Review published Ted Joans’ second book Beat Funky Jazz Poems. The following photograph is my own one.

Rhino (Rhino Review logo)

Rhino (Rhino Review logo)

the main totem of Ted Joans

A year later he left for Paris.

Once in the french capital he immediately wrote to André Breton:

“Who am I? I am Afro-American and my name is Ted Joans (…) I was born in 1928, the year of Nadja [André Breton], Treatise on Style [Louis Aragon] and The Spirit Against The Reason [René Crevel]“

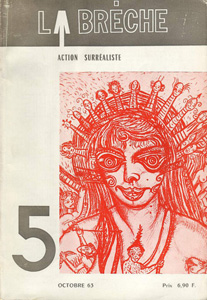

The extract of a letter to the “pope of surrealism” is reproduced in La Brèche #5 which came out in October 1965.

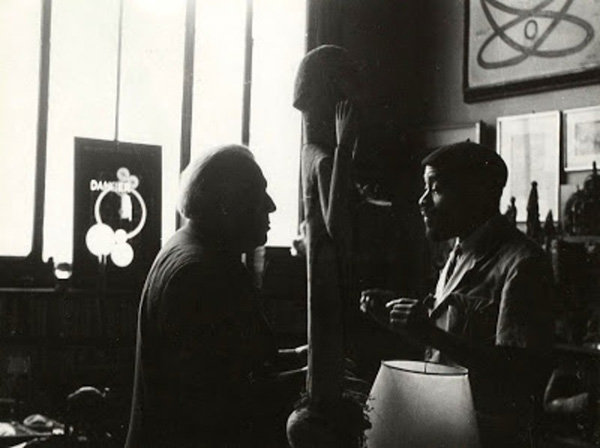

André Breton and Ted Joans at 42, rue Fontaine. Paris (André Breton’s home) 1966. DR

André Breton and Ted Joans at 42, rue Fontaine. Paris (André Breton’s home) 1966. DR

He wrote a poem, Nadja Rendezvous, in memory of André Breton. These verses refer to his different writings (Nadja, Les Champs Magnétiques) and the meeting with Joyce Mansour at the Promenade de Vénus cafe.

I first read his works in June 1942

I met him in June 1960

I last saw him in June 1966

I was going to see him again in 1967 June

But the Glass of Water in the Storm (1713)

of 4-2 rue Fontaine kept an almost forgotten rendezvous with Nadja in the Magnetic Fields…

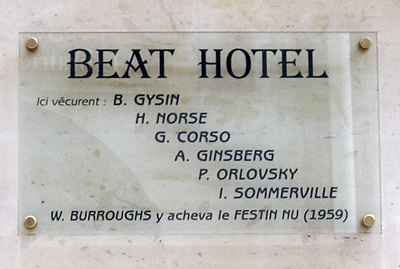

As soon as he arrived in Paris Ted Joans also contacted William Burroughs and Allen Ginsberg, exiled at the famous Beat Hotel, at 9, rue Gît-le- Cœur, a hotel managed by Madame Rachou, here there was an intense activity cultural, that France Culture (a public broadcasting company) endeavored to revive:

http://www.franceculture.fr/emission-l-heure-du-documentaire-docu-fiction-beat-hotel-rediffusion-de-l-emission-du-8-avril-2010-2

Here’s an extract of David Brun-Lambert and Guillaume Baldy’s Beat Hôtel (a documentary-fiction programmed 8th April 2010, 55mn)

On the 15th of October 1957, Allen Ginsberg and Peter Orlovsky turned up at the reception of a nameless hotel, 9 rue Gît-le-Coeur, close to the Latin Quarter, they were greeted by Madame Rachou, widowed, she’d lost her husband in a car accident a year earlier, she managed a shabby establishment, known to be infested by rodents. Several months earlier she had welcomed an author Chester Himes, who was in disagreement with the racism in America.

William Burroughs newly arrived from Tangiers (he was still marked by his use of heroin) took up residence in room 23 on the 16th January, it was here that he finished The Naked Lunch ; at the same time Gregory Corso was writing The Bomb, and Ted Joans was elaborating the fresco The Chick Who feels off a Rhino. As mentioned earlier not only was the hotel a place of important artistic agitation, but also of (distinct or specific) morals, Madame Rachou saw on a daily basis her ragged lodgers write a stage of one of the most feverish artistic adventures of the XXth century.

Ted Joans’ fresco disappeared when the hotel was renovated following Mme Rachou’s retirement in 1963. It was not until 2010 that the following plaque was affixed on the wall, it has since become a luxury hotel, Ted Joans name is absent.

To read Olivier Ledure’s full article in English, click here

For the French version, click here