Art and Empire on the Shore of the Sahara

Ivan Klein

April 2021

Sahel — Art and Empire on the Shore of the Sahara

Catalog of the Metropolitan Museum — (along with some memories)

Personhood

Out of that sand and heat, that scratch of life —

a beat, a heart, a sense of being.

A blind old Hausa poet, flies buzzing around his eyes, sang, “Life teaches us cruelly” in an airless mud hut in the old city of Kano, Nigeria, long ago, when I was an almost innocent young man barely comprehending the import of his words. — Another line about an old man’s penis being like rag on a branch. I don’t recall the exact translation, but that was the gist of it. — No fooling around with the naked truth there on the edge of the desert.

The formidable Metropolitan Catalog, particularly the section “Praying for Life” evokes the thought of the above encounter and the memories of the two years my wife and I spent in the region as teachers in the late 1960s.

And a very hard life it was on the edge of that encroaching barrenness that was once an ocean. A life marked by subsistence farming, the herding of underfed cattle living on scant fodder and, in our time there, deadly tribal enmity culminating in what was called the Biafran Civil War.

The current political turmoil, especially in the northeast, of Boko Harem (lit. western learning is forbidden) with the potent recruiting line, “They don’t care about you,” which given the state of things is mostly irrefutable.

In “Praying for Life” Souleymaine Bachir Diagne describes a life force whose only instinct is to grow stronger, as a common thread among all the traditional cosmologies of the Sahel. This in the face of those contrary forces always at work — climatic, political, societal. How hard the people worked to extract a living from that marginal land, and what a remarkable ability they displayed to wait, to suffer and to endure all that came their way.

Our second year in country, we returned to Maru Teachers Training College, past the northern railhead at Gusau and a good way toward the near desert capital of Sokoto after spending the hot season breaktime on the elevated Jos Plateau. Amazed to see that everything had prematurely turned green where only cracked brown earth was expected. It was two months before the short rainy season usually got started and even the oldest of the local villagers couldn’t remember rain coming so early or the abundance of getting two crops out of that stubborn, unyielding earth.

A five-year drought would follow that illusory abundance, and one Sunday morning in the spring of 1974, I found myself staring at a picture of a starving mother and child on the cover of the New York Times Magazine taken somewhere in that parched land I had come to know just a bit. Mother and young child staring out at the world in that abandoned extremity of need that the more fortunate nations were barely acknowledging, let alone addressing.

We have a three-year-old son by that time, the apple of my eye, but my wife is somehow overindulging him that particular Sunday morning, at least by my lights, and after a less than conclusive verbal exchange with her, I throw an ill-considered punch at the immovable living room wall. Immediately my hand assumes a grotesque shape, the knuckles in recession and the whole assuming aspects of a claw.

I put it to my chest and walk the eleven blocks uptown to St. Vincent’s Hospital Emergency Room where they give me ice in a medical glove and set me up for x-rays. Everybody super nice — the red-headed intern takes a look at the mess and asks, “What happened to your hand?” in a thick southern accent. I mumble something about trying to put it through a wall, and from the depths of his southern collegiate experience, he summarizes, “the old hand through the wall routine.” (No psychological referral called for.) The black x-ray technician with the same question gets the same reply and very decently urges me to relax. I thank him, but really all the frustration with the usages of the world temporarily dissipated with that one blow.

There’s a Hispanic mother in the waiting room struggling with her over-indulged pre-teenager. You can tell about that sort of thing almost instantly. He gloms on the ice pack and my messed-up mitt. Faker that he has been allowed to become, he sees my hand is really fucked up. I hope he gets past the impediment of his spoiled youth as a young man but think the odds rather long against.

Wearing a sling on my way home, I stop at the W. 4th St. basketball court and watch a few minutes of a hard evolutionary game outside the fence of what’s known as the box. A young black kid, a fellow spectator, digs my sling and so on, understands it as real life….Two recessed knuckles on my right hand to this day as a memento of the occasion.

∗∗∗

Adobe — mud/sand/water shaped into habitations with walls to shelter the married women inside (purdah). Clouds of dust blowing down from the Sahara in January and February. — Nose, throat, ears, eyes infiltrated. Wrapped cloth about the faces of people in the know — desert people. What they call the Harmattan wind. — Harmattan — Arabic for evil thing.

Prayers to the One God / for the power / to live

My memory fills us in on the map. — between Zaria and Sokoto. — Kano to the east forming a diamond with Katsina at the top.

∗∗∗

My last remaining African sculpture — an ebony head sold to us by a wily squint-eyed Ghana trader who made the rounds of the contract teachers and volunteers.

The superb figures of the praying man and the elongated Dogon prisoner in the Met Catalog, the pendent figure of a man of stark living power. The catalog ordered online during the pandemic lockdown. — Thick, heavy with memories when I pick it up.

Adamu Yola —

Our steward, like the first man. — Sweet, decent, flawed, like all men. — That time he started to raise guinea fowl and the local variety of spitting cobras began a hissing congregate in his backyard. — A particular instance when he left his wife of convenience and necessity, purchased for the bargain basement price of two Nigerian pounds, with a long branch to fend off a particularly truculent such cobra and peddled madly off to Maru village to fetch the maciji (snake) man. Returning with that worthy, teeth and lips bright orange from serious indulgence in the Kola nut, his simple traditional white cap a bit askew, a certain insouciance to his stride, he proceeded to do his magical stuff: he is on his belly about twenty yards from our fragile pre-fab house with that damn spitting cobra (distinguished as a sub-species by the salmon-colored blaze on their chests when they rise up) as this one is doing, fully hooded in the moment, raising himself above the man, who raises himself to look that snake dead in the eye. When it commences to sway, the snake man sways with it, and when the cobra darts its head menacingly, the snake man darts his head just as quickly. Finally insinuates himself, is stronger in mind than that deadly creature. Becomes intimate by tonguing the snake’s tongue, fools around with it some more and then places it in the wide pocket of his caftan before heading back to the village with a crooked grin on his face. My wife thought she saw him discharge something down the cobra’s throat, perhaps to tranquilize him, but I think to this day that it was the superiority of human consciousness that we witnessed and that somewhere in that picture of the fearless Hausa villager was an African gloss to the shaming of Adam and Eve. — Perhaps even a rethinking of man’s capacities and potencies.

It hurts me to think of that good man, Adamu, left to his fate in the stressed far north of Nigeria. The Ghana trader on one of his periodic rounds had sold us a large carved figure of a shackled prisoner/slave. The Hausa-Fulani people having historically been middlemen in the trans-Sahara slave trade. Adamu, of Hausa ethnicity, expressed a distaste for it. It reminded him, he said, of the bad times.

I sold it along with some really good pieces for a few bucks when we were back in New York and I was broke and out of work. We’re left with a couple of decent wood plaques mounted on the brick wall of our kitchen and a generic ebony head of a northern type that I keep in my study. My ongoing respect for and relationship with this last sculpture of ours. My obsessive care to see that I have a clear view of it and it isn’t obscured by the general clutter around it. The head is covered by the suggestion of a Muslim cap of a type we were familiar with. What I have come to see as the purity of spirit that the sculpture embodies. Representing the nobility, mystery and stoicism of the people we were among for those two years. Although there is probably an element of fetishism in my relation to the object itself, this is the way I can’t help but feel.

The great Sahara creeping southward with the dryness afflicting the globe, further marginalizing people across a broad belt of sub-Saharan Africa. The population of Nigeria has doubled in the fifty years since we taught there, and over the whole region desperate young men are impelled to head toward eastern ports in North Africa, brave the Mediterranean in packed, unseaworthy vessels. The object being to secure some sort of place in Italy, Greece, and onward. Using whatever blood money their impoverished families have come up with for this ghost of a chance.

∗∗∗

Notable from the Catalog:

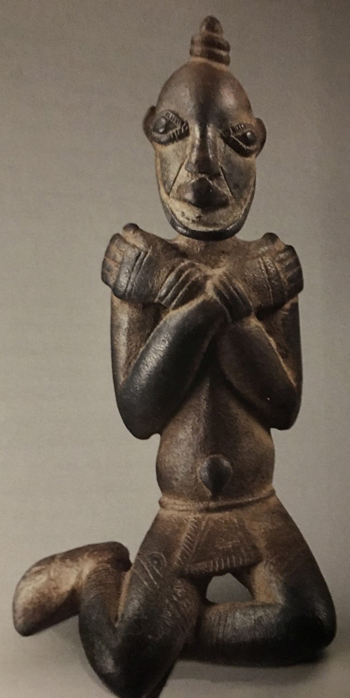

“The Praying Man” (#145) — A sculpture of stark unmitigated devotion to Allah. The rub is the Islamic prohibition against representation of the human figure. The text that accompanies it cites a mid 1980’s cultural study of the region that asserts “Islam was rethought, rephrased remolded to the sub-Saharan cultural milieu.” — A way to look at this 12th to 14th century product of Mali as a near miraculous fusion. — An organic form of expression deeply woven into the world feeling of their people.

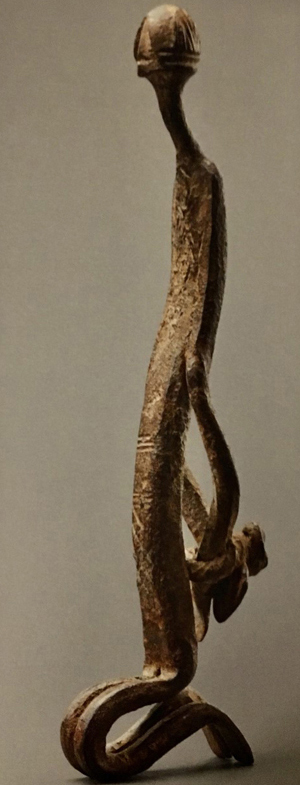

“Prisoner” (# 148) — As for this arresting and ultra-modern figure produced by the supremely gifted Dogon people sometime before the mid-twentieth century, it has existential qualities far beyond the elongated semi-abstractions of Giacometti, for example, which seem pallid and merely conceptual by comparison. Featureless, anonymous, by profound design, I believe, it captures the essence of imprisonment, leaves us with an emptiness in the pit of our stomachs for where our humanity leaves off.

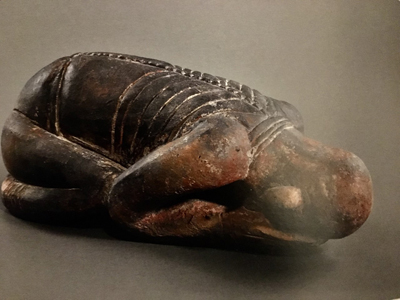

“Pendent” (#149) — Male Figure with Crossed Arms— bronze, Mali, 9th to 14th centuries. — Compelling, magnetic, commanding attention to its unwavering gaze. A product of middle Niger civilization according to the text. — The River Niger of myth and majestic reality.

The great modern composer Morton Feldman wrote of Rembrandt that “there was only the integrity of the creative act.” That is, all other considerations fall away in the doing. That pendent of a man, radiating the immediacy of its existence, leaves us with the same impression.

The art of the Sahel, spare, a necessary excrescence of consciousness. Carved out of that nearly arid world. — Living despite all and everything that worked against it coming into being. — Like all art, living miraculously because it must.

The Catalog (continued) on the Life Force in the cosmology of the Sahel: “The purpose of the force is to be more force…and most important, it is the role and responsibility of individual beings to participate in that continued cosmic movement of an increase and intensification of the force of life…”

Yeah, I remember a particular conversation with a student named Alhaji (a name that is also an honorific for one who has made the pilgrimage to Mecca). — A young fellow who had mechanical skills and worked on our motorcycle and chronically malfunctioning market-bought wrist watches. — Just an afternoon greeting in the mellow time of year — August, I think it was — both of us alive at that very moment in the sun. Yet I remember it quite well. A soft breeze blowing across the flat land and both of us aware that we were alive and grateful in the moment. — What I brought back from Africa other than a few wooden carvings. — The spirit of a place that somehow lived and breathed simply and truly. So it seemed to me.

Taking a Pan American flight that touched down at the major cities on the West African coast before taking that turn over the Atlantic and heading for New York City and home, I wished that my spirit had been purer, that I had managed to do more….

◊

Ivan Klein published Toward Melville, a book of poems from New Feral Press, in July 2018. Previously published Alternatives to Silence from Starfire Press and the chapbook Some Paintings by Koho & A Flower Of My Own from Sisyphus Press. His work has been published in the Forward, Urban Graffiti, Otoliths, and numerous other periodicals.

For information on Ivan Klein’s new book

The Hat and Other Poems and Prose from Sixth Floor Press

click here →

Other essays, reviews and poety by Ivan Klein on Arteiodolia→