Time Outside

patrick brennan

May 2014

The Music of the Temporalists (by “André Pogoriloffsky”) Contributes

to the Musics Beyond the Clock — — — — and What about Rhythm?

In the beginning of this year, I received a very formally worded e-mail from out of nowhere entitled Book on Musical Time Theory.

Dear Mr. patrick brennan,

I am an independent music theorist and this is my book …The Music of the Temporalists …

It describes a perceptual approach to time in music. …

I hope this may be of some interest for you.Thank you for your time,

Andrei Pogorilowski

Now, if you want to read anything about time in music that takes it seriously and tries to deal with it in any kind of systematic way, it can be pretty hard to come by. The huge majority of formal literature on music (especially if you rely on a low budget resource like a public library and aren’t chasing down the newest obscure scholarly publications) is based on the theories and assumptions of 17th to 19th century European concert music with some 20th century extensions taking up a bit of the slack. The emphasis is almost entirely on tempered pitch, melody, diatonic harmony and the precedents for methods of construction within monological composition formats, almost nothing at all on rhythm and time, which is habitually treated as a blank container for the “real stuff.”

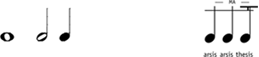

One exception I came across years ago was Leonard B. Meyer’s The Rhythmic Structure of Music, which, borrowing terms from syllabic patterns in poetry, gave attention to the prosodic relations among sonic events, which is to say — whether a perceived set of two consecutive sounds begin with an accent, as with the word coo-kie, (a trochee in poetic technicalspeak) or lead up to a final accent as with be-fore (an iamb) etc. etc. etc.. Then, there’s the way phrases themselves may gather within similar from-to emphasis formations and how such small constellations tend to nest themselves within more widely expanded prosodical relationships. Useful as that can be for breaking down Haydn, it’s also one more way to understand why, say, what Charlie Parker actually plays is so different than what a conventionally notated version of the same communicates.

As for the wealth of music outside Euroclassical neighborhoods (which is traditionally one of the more rhythmically under-developed communities of practice around), most texts concerning time and rhythm are for a musician’s practical application – the whats to do. I haven’t seen much that addresses the thinking, or the why, or the how – in other words, the activating concepts, or theory, of it. Now, talking with musicians (and playing with them especially), however, can be another thing completely: there’s a lot — a lot— going around; however, a huge gap exists between what circulates among musicians and what gets both written and published beyond those immediate circles. This might also be because, contrary to the impression given by the schematic representations of conventional notation, an appropriately developed interpretive and structural theory of rhythm would likely be more complex and unwieldy than diatonic harmony and all the variations of canonic writing combined. There may be more, rather than less, to address,

While there definitely have to be some that I’ve missed, there nevertheless still seems to be very little published in English about rhythm theory that’s specifically relevant to jazz or other African-American musics (I’ve heard about Charles Kyle but have yet to check him out). There seems to be just a bit more in circulation regarding some continental African musics – Kwame Nketia and Gyimah Labi, for example. John Miller Chernoff’s African Music, African Sensibility indirectly, but very lucidly, describes some of the structural and ethical principles of musical construction in Ghana that can translate pretty well to other Black Atlantic contexts.

And, if a reader turns to cognitive science or psychology explicitly in relation to time in music, among what’s easily available, it seems that, within the gated communities of published PhDs and musical literati out there, most seem to be aware of little more than Mozart et al and the Beatles, which makes for a very narrow selection that only underscores that musical time and rhythm seem not to be taken particularly seriously either by the “mainstream” or the certifiably “well educated.” I wonder why.

So, given its rarity, any book attempting to deal with a “perceptual approach to time in music” would seem at least worth checking out. This, accompanied by a personal message from an independent musical theorist, definitely played on my sense of camaraderie. I did write back to him to ask why he contacted me in particular, but I didn’t get an answer to that one. Curiosity, however, drove me to order it regardless.

The Music of the Temporalists adopts a strategy kin with Jonathan Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels or Edwin Abbott’s Flatland: A Romance of Many Dimensions, which is to invent a fantasy or sci-fi environment so as to more fluidly talk “outside the box” about something misunderstood, ignored or suppressed in the “real world.” A piano playing Parisian pharmacist happens to catnap unsuspectingly into a parallel human world that constructs music on the basis of intervals of time rather than intervals among pitches. A dreamtime of two years takes him through a crash course in their music and its theoretical frameworks. The author’s choice of such a format gives me an impression that his considerations have been meeting with more resistance and incredulity than he’d really appreciate. But, while his musical ideas may not be conventional in terms of his milieu, in no way are they crazy.

Having written this book under the pseudonymn of André Pogoriloffsky, Andrei Covaciu Pogorilowski — who lives in his hometown of Bucharest, Romania — relates that around 1989 he began

juxtaposing on my piano short passages (3-4 bars) from the few dozen musical compositions I then happened to know by heart – without a break and in each excerpt’s original tempo. I was amazed by the fact that I thus instantly passed from one tempo to another without having any idea whether they established or not one of the “simple arithmetic” ratios specific to rhythm theory.

What he means by “arithmetic ratios” is whether all of the consecutive tempos he was playing were linked to a single reference pulse, with each being, for example, either 2, 3 or 4 times the speed of that pulse the way that ordinary musical notation represents these as 8th notes, triplet 8ths or 16ths, etc.

By conventional standards this would be mixing tempos “freely,” but he developed the concept more deeply, memorizing a spectrum of tempos from “slow” to “fast” until he was able shift from one to another at will. He realized that he was discovering another potential arena of musical syntax, one directly based on pulsation that couldn’t be notated in the common system that relies upon a central tempo, bar lines and relative note values represented by whole, half, quarter notes and so forth. So, he invented his own elegant system for notating musical time that can accommodate successive tempo shifts not anchored to a reference pulse.

By the late 90s, he began integrating these concepts with what’s being studied through cognitive musicology about human perceptual capacities and learned that these built-in physical and psychological thresholds can help define a systematic theory of musical time based on the commonly experienced hots and colds of human perception.

The Music of the Temporalists imagines a musical culture where such a sensitivity to variations in pulsation has been developed with the same thoroughness that European musicians have over centuries dedicated to diatonic harmony (or, for that matter, that classical Hindustani musicians have to raga and tala). Pogorilowski portrays a world so parallel to the high end pan-European world as to be filled with conservatories, a linear historical evolution, theoretical lexicons and heated differences of opinion.

He points out that the ability to recognize intervals, chords and functional progressions in the pan-European diatonic system is a learned, rather than a given (or “natural”), skill. He further relies on cognitive science to assert that an ability to accurately modulate from tempo to tempo the way many composers have already run chord changes rests easily within human capacity but would depend no less on cultivated experience and discernment. He proposes a plausible “perfect time” sense analogous to perfect (or even relative) pitch perception, a sort of elaboration of what ethnomusicologist Richard Waterman has articulated as a “metronome sense,” an interior hearing of a pulse that animates participation in so many pan-African musics. Or, just check out any number of drummers, percussionists or dancers concerning their recognition of time densities (one could think about the tempo precision familiar to ceremonial drummers who guide and accompany the transformation of consciousness through altered states) to confirm that this has always been happening. It’s not globally exotic.

Perhaps most interesting is an aside of his that these experiences, through repetition, develop each individual brain in particular ways, which is to say that they develop literally different brains with correspondingly dissimilar predilections and affinities. Therefore, the recognition of harmonic relationships, tempo strata or rhythmic constellations may come to seem natural and immediate for those already accustomed to them, but this wouldn’t necessarily be so for those bringing another experiential palette to these same sounds. This, for me, says something about the complications of cross-cultural, or even cross-genre, musical listening and furthermore about the leaps listeners often have to make when encountering any really new music.

Along the way, there are some moments where his book can become an excruciating read. The translation into English can get awkward at times, and some inexplicably eccentric typographical usages (such this use of „quotation marks”) can be a little distracting (Recently, I was watching the credits to Polish film that did the same thing with quotation marks. Maybe it’s an Eastern European convention.). Sometimes, the interludes of fictional narrative can seem to bog down getting to the musical ideas that his book is really about, while the entertainment value of some of its tangents of humor are definitely subject to the personal taste of the reader.

Nevertheless, Pogorilowski’s musical conceptions clearly come across as hard earned, serious and very well considered. There are also a few short scholarly papers of his that are accessible through academia.edu that, along with the technical portions of this book, help spell these out. The man has really done his homework, and the book’s accompanying bibliography could keep you reading for a good couple of years. It offers a great resource.

There’s a geeky aspect to Pogorilowski’s incorporation of quantitative science so thoroughly into his system, but what he’s really exploring and proposing, with all of the excitement of a composer in pursuit of sounds yet unheard, is an enriched poetics of feeling; and I mean this in a very, very literal sense. He’s not insisting that musicians lock with any of these tempos with some kind of technocratic accuracy, but rather with the identifiable character of each general region. Each pace corresponds with different conditions of perception, each with its own body base of sensation and states of awareness, each with potentially unlimited gradations of feel.

And, by the way, there are even scientific arguments circulating these days on behalf of feeling as pivotal to what’s been long touted as rationality itself. Drawing on the examples of the impaired capacities of people who’ve suffered particular areas of brain damage, cognitive scientist António Damásio has persuasively argued (in Descarte’s Error, among other texts) that coherent rational thought without feeling, without emotion, is impossible, not the least of which is that emotion identifies a value which then keeps the comparative and computational mind focused. Without such constraining feelings (which, through preference, impose value), “pure” thinking lacks any referential environment for prioritizing any one thought over another. Damásio portrays thought as a process played out by the brain in the “theater of the body,” whose sensations in reaction to hypothetical (as well as actual) conditions substantiate and inform more complex and coherent streams of thought.

Returning to Pogorilowski, his tempo spectrum aptly maps regions of sensation, feeling and sensibility, but their conceivably unlimited combinations and interactions enormously complicate the range of potential feeling these possibilities suggest. Furthermore, he doesn’t propose any of this as a replacement for anything that’s already found musical formulation, but rather as an enriching, yet to be cultivated, supplement.

I haven’t come across any recorded examples of what such music could be like, but he does present a very short example in his paper A Matter of Perspective (examples 2 & 6) that I’ve converted to MIDI for a quick listen.

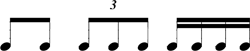

This is the phrase in conventional notation:

This is the same phrase in Pogorilowski’s custom notation:

The phrase is repeated here a number of times:

[ezcol_1third] [/ezcol_1third] [ezcol_1third]

[/ezcol_1third] [ezcol_1third_end] [/ezcol_1third_end]

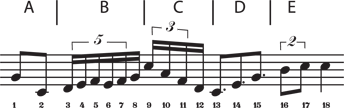

(A) The first two sounds mark a pace of 85 BPMs

(B) The next six mark 214

(C) The next four — 320

(D) The next three — 107

(E) The last three — 72

Well, What about Rhythm?

John Cage, who rhetorically argued for getting the human out of music as much as possible in favor of “sounds in themselves,” took note of four basic sonic parameters: pitch, amplitude, timbre and duration. Duration distinguished itself as the only organizational reference capable of including all of the others. In this regard, he often turned to that time honored regulator of human behavior that began doing its work from way up in church towers back in late medieval Europe, the clock.

Interestingly, rhythm is not really an intrinsic constituent of sound, as Cage all but declared. It’s a pattern of biological activity, an aspect of people, not of sounds in themselves, but rather a perceptual component of people’s interaction by way of sound. Pogorilowski, while aware of this, emphasizes the quantitative supports of his conception in the interest of clarity and simplicity, but what listeners and musicians would have to make of it perceptually would finally be in terms of rhythm.

Rhythm was also of great importance to Edward T. Hall, an American anthropologist who began his work in the 1930s and emphasized friendship (in sharp contrast with other more “disinterested” anthropological procedures) as his primary approach to participant observation. His accomplishments include initiating intercultural communication as a formal area of study, studies of non-verbal communication — as in the case of what he came to call proxemics (interpersonal spatial distance as a language of social communication), studies of cultural notions of interactive time and his conceptualization of technology as an amplification or extension of the human body, an idea foundationally influential on Marshall McLuhan’s renowned insights.

“Viewed in the context of human behavior, time is organization.” wrote Hall in his 1983 The Dance of Life, where he discussed the findings of William Condon, a researcher trained in kinesics, philosophy (with a special interest in phenomenology) and psychology, who coined the term entrainment: “the process that occurs when two or more people become engaged in each other’s rhythms.”

Condon spent a year and a half (four to five hours a day) studying 4 1/2 seconds of Professor Gregory Bateson’s films of a family eating dinner. He wore out 130 copies of this 4 1/2 second sequence. Each copy lasted 100,000 viewings.

Condon used sophisticated time-motion analysis to “identify the building blocks used in the organization of human behavior” and discovered correlations between components of speech, the body’s accompanying microgestures and brain wave frequencies, a coordination of a person with one’s own rhythms that Hall refers to as self-synchrony. He focuses briefly on a 9 word, one second long, phase spoken in the film clip.

During this one second the subject’s arm is precisely coordinated with the theta wave pattern; her eye blinks are in sync with the beta wave pattern; the alpha rhythm is in sync with the words or vice versa. Condon states: “These basic rhythms seem to become part of the very being of the person. …His whole body participates in that rhythm and its hierarchic complexities. In fact, the oneness and unity between speech and body motion is truly awesome.

Hall notes that

The definition of the self is deeply embedded in the rhythmic synchronic process. This is because rhythm is inherent in organization, and therefore has a basic design function in the organization of the personality. Rhythm cannot be separated from process and structure; in fact one can question whether there is such a thing as an eventless rhythm. Rhythmic patterns may turn out to be one of the most important basic personality traits that differentiate one human being from the next. All human rhythms begin in the center of the self, that is with self-synchrony.

… No matter where one looks on the face of this earth, wherever there are people, they can be observed syncing when music is played. There is a popular misconception about music. Because there is a beat to music, the generally accepted belief is that the rhythm originates in the music, not that music is a highly specialized releaser of rhythms already in the individual. … Music can also be viewed as a rather remarkable extension of the rhythms generated in human beings.

What’s especially important here is that rhythmization of sound (which includes the playing of silences) specifically humanizes musical sound. Rhythm derives from the actual people who generate the sound and interacts similarly with its ever too human listeners. While it can be mapped and quantified to an extent, rhythm’s no abstraction; rather, it figures the palpable shape of action. To study the dynamics of musical time is also to study ourselves.

Pogorilowski’s discoveries and suggestions add to a body of musical alternatives to clone time. Clone time substitutes continual replications of unvarying, mathematically equivalent beats for the more “imperfect” microvariabilities of reciprocal, biological time. As part of a progressively more rationalized industrialization of musical activity, the growing predominance of clone time in music dates back at least as far as the historic Invasion of the Click Track Snatchers that caught up to the innovations of overdub recording.

A symbiotically cultivated preference for hypersimplified, mass produced, prefab musical time is one example of the ambiguous chicken-egg relationship that arts can assume with their audiences. Any artistic demonstration functions as more than reportage but also as example and maybe even as instruction. How much of listeners’ (and music generators’) attraction to clone time results from hearing little else?

Electronics may have made this extreme degree of regularization attainable, but technologies themselves don’t cause such regulation but only offer more opportunities to do so. As a counterexample, according to Jeff Chang, Public Enemy (back in the day) would systematically sabotage the regularity of their own beat samples by deliberately setting tracks slightly off phase or out of tempo during performance. Similarly, the variety of rhythmic potentialities that Pogorilowski outlines demonstrates an optimistic confidence in the range of feeling and awareness that humans are actually capable of through their relations with sound.

That Pogorilowski was moved to write a book on his ideas indicates that he’s aware of the core sociality of musical structures. However, remarkable an idea one may develop concerning sonic organization, these concepts still need to be somehow communicated among a community of participants. He seems to be reaching for a top down jump start through placing some grain-of-salt tempered hope in academia. Seizing on the formal conservatory model, he implicitly suggests that within a context where young musicians could be trained from a young age to spontaneously recognize tempo distinctions, the necessary skill set could evolve that would render such a music playable. But, there’d also have to be somewhere in mix some musical designs to play, but these haven’t been composed yet.

Of course there are now computers to produce such sonic material in the interim, but there’s still the internal topography of how to enact and conceive such soundscapes to be explored and worked out by actual people. Anybody can listen to anything on an I-Pod, but that doesn’t instantly translate into being able to do it oneself, much less dream any of it up. His concept faces this challenging evolutionary conundrum.

It’s possible that some tenured composer somewhere might explore these possibilities and begin to teach a group of students how to play using a tempo based vocabulary. and perhaps that could jump over the ivy covered walls into the vernacular world from there. But, I’d suspect that a grassroots evolution, where nobody’s going to get (or have to wait for) funding anyway, might be even more likely, though this scenario would turn neither simpler nor easier.

Somebody may get the fever for this notion and find a personal sound or language with it, and, with enough charisma and determination, develop a small sonic community that actually produces a sound that grows an audience and inspires other musicians in the way that Ornette Coleman or Harry Partch did — or maybe a whole band might explore this notion collectively. These could be the next steps where this musical possibility finds a language that can be socially transmitted — always a long shot, but never genuinely impossible.

Pogorilowski is also aware that musical time isn’t quite so simple as successive pulses, but that rhythm also variably complicates pulses with emphasis, gestalt perception and multileveled coordination; and in relation to a pulse, rhythmic statement often incorporates a variety of tempo strata simultaneously. Pogorilowski’s concepts just might find more precedent and parallels outside the concert hall tradition among the polyrhythmicists of the Pan-African musical worlds.

In this context, rhythm functions even more importantly as communication than as measurement. It interposes a social interface, a common matrix for further elucidation and dialogue, that configures identifiable meeting points around which participants may converge (or diverge) within a dynamic relational system that incorporates the effects of participants upon each other.

Rhythms deliver complex assemblages of pulses with a simultaneous assortment of the contrasting perceptual velocities that Pogorilowski has outlined. Polyrhythm further intensifies this with widely expanded interconnections and differences that include the multiple relations between each pattern and the composite presence of all its constituent rhythms.

Polyrhythms also launch perceptually mixed messages. One pattern may prosodically contradict another, where the weak accents of one component may coincide with the strong emphases of another. Polyrhythms in this way narrate so much rotating imbalance at (at least) one perceptual level that they may impel motion in order for a person to retain one’s own balance (i.e. dance). Polyrhythm’s contradictory impulses may so confound perception as to short circuit it into an altered state, which may be relevant to African art historian Robert Farris Thomson’s assertion that “the formal goal of African religion is ecstasy.”

Ecstasy traces back to the Greek term ekstasis (ek — “outside or beyond” + stasis — “the place in which one stands”) — “to stand outside oneself” — which is, in effect, an altered, or expanded, state of awareness. To play, to “hear” polyrhythm requires an alteration of “ordinary” consciousness, an ability to pay attention multidirectionally, poised somewhere between highly focused consciousness and more diffuse, peripheral, background awareness, a kind of both/and yes+no perceptual condition.

While this sort of multidimensional conceptual framework is staple to Pan-African polyrhythm, jazz musicians in particular have sought ways to maintain this condition while incorporating a spontaneous flexibility that allows rhythms to maintain such connection while not being locked so closely to a fixed pattern as in so many other Pan-African ensemble constellations. The range of improvisation displayed by the young Louis Armstrong, was expanded upon by the bebop rhythm section — think about Max Roach, Roy Haynes and Bud Powell.

Elvin Jones, who accomplished this across the board, displays a lucid (and famous) example in the transformation of African (or Creole-Afro-Latin) patterns during the opening to Acknowledgement on the John Coltrane Quartet’s studio recording of A Love Supreme. The drum pattern continually varies without either locking into a fixed vamp or losing the feel of this motion construct.

Other ‘60s rhythm sections expanded this flexibility ensemble-wide: Ornette Coleman’s, the Tony Williams / Miles Davis rhythm section, the CJQ, Charles Mingus. Some musicians have been exploring multiple polyrhythmic strata as aspects of rhythmic harmony. There’s work being done with multiple tempo polyrhythmic organization. In place of a single reference tempo, there may be a spectrum of concurrent pulses, for example, in ratios of 3:4:5, simultaneous 7 & 8, fractal relationships like 4:6:9 and more than that. Then there are also the possibilities of metric modulation, speech and breathing patterns to consider as well. For all their technical and conceptual challenges, the point is not their apparent “intellectual” complexity, but the expansive, very tactile, feeling languages being developed.

Pogorilowsky’s notions of flexible, perception calibrated musical time have probably already been explored more in jazz contexts than elsewhere. There’s likely kinship to be found in the varieties of postmetrical time explored through free jazz rhythmic organization. Consider, for example, Sunny Murray’s precedent, who deliberately plays contrary to beat and measure patterns, at times evoking a drone effect, but within that a plurality of pulses susceptible to multidirectional interpretation. This, in combination with the pulses incorporated by other players, sets a palette for the kind of perceptually guided time blocks that Pogorilowski has mapped.

However, this music is arrived at more “intuitively,” being based on the immediate events & interactions in process while playing, versus Pogorilowsky’s more top down, systematic approach. Given however, that musicians generate pulse based on their own body processing of temporality, there’s a good probability that instances of Pogorilowsky’s pulse modulations are already happening in some of this music, but nobody’s yet running around with sensors trying to verify any of that, which, given the complexity of temporal constellations being generated, would offer a pretty arduous documentary challenge. This isn’t to say that the variety of temporal sequencing that Pogorilowsky has described is being consciously applied, only that the possibility could find its most immediate application here. And still, just to think about time this way might open up some doors.

Pogorilowsky’s research into cognitive science in order to support his explorations deserves some real respect, but his efforts should also be considered in alliance with the collaboration of scientific research with musical time that’s been pursued by Milford Graves, who’s turned to the pulses of the literal, individual human heart as a musical resource.

Decades ago, Graves expanded his percussion practice to engage acupuncture and herbalism alongside prolonged research into the human heart as the principle generator of rhythm. Already well versed in Nigerian, Haitian and Cuban drum languages, he understood that a particular wisdom concerning the interaction of musical time with heart rhythms had already been empirically worked out by musicians centuries ago without the benefit of experimental analysis and theory. He began recording heartbeats to inquire into their peculiar musicality to discover that a healthy heartbeat is actually a syncopated and polyrhythmic one, that amid the more evident primary pulses are more temporally irregular concurrent rhythmic pulses. A swingingly irregular heartbeat is more resiliently disposed to ably adapt to the interferences of stressful episodes.

Not only do the rhythmelodies of the well recorded heart recall the intricately flexible readiness of Nigerian and Cuban beats, they resemble most the kaleidoscopic pulses of free jazz, a telling confirmation, if there ever was one, of the extraordinary aptness of Milford Graves’ own musical innovations. Graves has further synthesized his rhythmic acumen into his healing procedures. The rhythmelodies of the heart further inform his music and the music applies to help therapeutically harmonize the heart.

Inspired by Graves’ musical work and his evolving discoveries, Steve Coleman has recently recorded a series of compositions on an album entitled Functional Arrhythmias that encompass some of the rhythmic interactions of a variety of systems in the human body, all linked with the irrational rhythms displayed by healthy human heartbeat patterns. As he puts it, “All of the activities of the human body are connected in a miraculous fashion, like a giant musical composition that is constantly and spontaneously changing based on interactions with its environment.”

Although still well at the social margins of what’s called “mainstream,” an actionable and richer awareness of the networks of human time, of those biological rhythms unlisted on the clocks of technical time, continues to develop — especially within music, while also blurring beyond these thresholds into science, healing and sociality. There’s a plurality of discoveries, rediscoveries, experiments and syntheses in motion. And a healthy ecology, whether biological or social, thrives on these genetic — and memetic (and dispositional) — diversities of cross pollination. Here, Andrei Pogoriloffsky has added something distinct and considerable to the mix. How all these strains may eventually interact remains yet something to hear.

___________________________________________

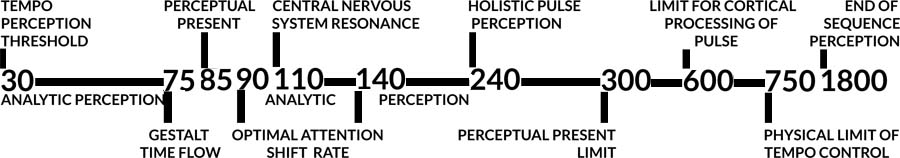

Here’s a sketch of the tempo spectrum that informs Pogoriloffsky’s conceptions:

[ezcol_1third]8.57 Beats per Minute: [/ezcol_1third] [ezcol_1third]

[/ezcol_1third] [ezcol_1third_end] [/ezcol_1third_end]

The maximum span of attention extends up to a range of about 5 to 7 seconds. The ability to exactly predict and sustain a steady pulse at this very slow rate wobbles pretty unreliably.

[ezcol_1third]12 Beats per Minute: [/ezcol_1third] [ezcol_1third]

[/ezcol_1third] [ezcol_1third_end] [/ezcol_1third_end]

Accurate expectations and perception of pulses’ proximity to each other almost completely fades out beyond 5 second intervals. Notice how much your mind tends to wander between beats.

[ezcol_1third]30 Beats per Minute: [/ezcol_1third] [ezcol_1third]

[/ezcol_1third] [ezcol_1third_end] [/ezcol_1third_end]

However, once within the thresholds of short term memory, where consecutive pulses speed up to about one beat every 2 seconds, or 30 beats per minute (BPMs), a person’s time sense is able to shift from rough estimation into more exacting perception. While this approaches the slowest pace at which steady tempos may be accurately recognized and maintained (without holding on to any faster subsidiary beats in between) an awareness of an open gap, of a waiting, between each sound, continues to linger. Here, the tempo expectation can feel manageable, but the moments between still leave lots of room for distraction,

[ezcol_1third]75 Beats per Minute:[/ezcol_1third] [ezcol_1third]

[/ezcol_1third] [ezcol_1third_end] [/ezcol_1third_end]

As tempos speed up to around 75 BPMs, this sensation of a gap between pulses smooths into a gestalt perception of a more connected, continuous flow, and at 85 BPMs, becomes ideal for noticing an immediate succession of pulses and for a sustainable awareness of a “perceptual present,” or arbitrarily designated “now.”

[ezcol_1third]85 Beats per Minute:[/ezcol_1third] [ezcol_1third]

[/ezcol_1third] [ezcol_1third_end] [/ezcol_1third_end]

The optimal rate of attention shift, that is, the ability to move an intact awareness of the moment from instant to instant, functions best at a pace of each 2/3 of a second, or at about 90+ BPMs.

[ezcol_1third]90 Beats per Minute:[/ezcol_1third] [ezcol_1third]

[/ezcol_1third] [ezcol_1third_end] [/ezcol_1third_end]

Tempos from here up to about 110 BPMs correspond most with the temporal resonances of the human central nervous system.

[ezcol_1third]110 Beats per Minute:[/ezcol_1third] [ezcol_1third]

[/ezcol_1third] [ezcol_1third_end] [/ezcol_1third_end]

The ability to sustain a continuous shift of attention from one clearly identifiable “now” to a successive “now” maxes out just below 144 BPMs.

[ezcol_1third]143 Beats per Minute:[/ezcol_1third] [ezcol_1third]

[/ezcol_1third] [ezcol_1third_end] [/ezcol_1third_end]

Research is also suggesting that the maximum number of recognizable elements within any given perceptual present tops off at about 7.

Analytic perception of the individual identity of each pulse can continue up to about every 1/4 second (4 beats to a second, or 240 BPMs), beyond which, holistic perception, the tendency to gather successive pulses into grouped clusters, begins to predominate.

[ezcol_1third]240 Beats per Minute:[/ezcol_1third] [ezcol_1third]

[/ezcol_1third] [ezcol_1third_end] [/ezcol_1third_end]

300 BPMs, or 5 beats per second (a little below the tempo of Charlie Parker’s Koko), measures the near minimum span of a perceptual present and the minimum time interval within which a person way decide an action and still be able to stop it before it happens, which is to say, the minimum length within which a person is able to change one’s mind. Within a shorter time gap, it becomes impossible to recall an impulse to act due to the speeds at which neural prompts translate from brain to physical action.

[ezcol_1third]300 Beats per Minute:[/ezcol_1third] [ezcol_1third]

[/ezcol_1third] [ezcol_1third_end] [/ezcol_1third_end]

Tempos as twice that speed (10 beats per second, or 600 BPMs) reach the threshold of the minimum interval for cortical processing and rhythmization of a pulse.

[ezcol_1third]600 Beats per Minute:[/ezcol_1third] [ezcol_1third]

[/ezcol_1third] [ezcol_1third_end] [/ezcol_1third_end]

By 750 BPMs (12+ beats per second) exact control beyond very short bursts is just about totally gone; and about the fastest physically playable sequences race by at about 18 pulses per second. However, when I listen to this sample, this description doesn’t make a lot of sense to me, as musicians play faster than this all the time, especially drummers (and what about a roll?). However, he may mean discrete separate pulses versus faster composites of slower pulses. Still, there’s got to be an accuracy/discernment threshold at some point.

[ezcol_1third]750 Beats per Minute:[/ezcol_1third] [ezcol_1third]

[/ezcol_1third] [ezcol_1third_end] [/ezcol_1third_end]

At close to 30 pulses per second, sequential relationships among sounds blur beyond recognition.

[ezcol_1third]1800 Beats per Minute:[/ezcol_1third] [ezcol_1third]

[/ezcol_1third] [ezcol_1third_end] [/ezcol_1third_end]

With approximately 33 pulses per second (at 1960 BPM), the perception of pitch emerges at about 16.25 hz. close to the bottom tone of a piano.

[ezcol_1third] 1960 Beats per Minute:[/ezcol_1third] [ezcol_1third]

[/ezcol_1third] [ezcol_1third_end] [/ezcol_1third_end]

Many thanks again for this substantial and wonderful article/review!

Best regards,

Andrei Pogorilowski

great stuff to ponder and why not. somethings have become institutionalized and sacrificed to uphold the status quo. there is alot to be explored with time and feel in music.

An interesting article. Too Afro/jazz biased. No mention is made of the similar time work of Renaissance & Baroque musicians. Composers such as John Dowland used layers of rhythm & different tempi quite regularly; examine the score of ‘Lachrymae or Seven Passionate Pavans for 5 Viols’. Most recordings kill the complex rhythms in the piece. A direct result of Wagner’s hugely successful musical revolution in the 19th century.

Flamenco performers use similar complex rhythms and tempo changes based on the emotional needs of the ‘compas’ being performed. These rhythmic complexities can be traced back to Spanish texts published as early as 1532. South American folk music is another area that layers polyrhythms. Interesting and complex as African drumming is, please note that other cultures also use similar techniques but in different ways.

I have studied early music and Spanish/S.American music for over 30 years and I have noticed that all these forms, as well as jazz & many Eastern types of music are closely linked to the heart beat or pulse.

Stockhausen also noted the close relationship between key and tempo in Mozart’s symphonies and concerti. (e.g. for a symphony in C, a movement in C major is faster than one in F but slower than one in G.) I think the paper was published in Darmstadt about 1970-1980. He also has many studies that use variable tempi and different rhythms simultaneously.

This is a very interesting idea, but one that has been explored for several centuries. As you rightly say, academia doesn’t understand rhythms or their importance to a passionate performance.

Much thanks to David Stanley for greatly enriching this conversation in offering us some other places to look & listen for examples where we (and I) can learn still more.

Pogorowski’s book was, in this particular instance, read and commented upon from a specifically anglophone, Gumbo-American creole perspective & experience (somewhat emphasized as a counterbalance to the book’s apparent Euroclassical focus) and oriented toward what musicians might do with these concepts — now — versus a more inclusive music historical cataloging of all previous instances where variable pulse has been consciously applied.

One might also mention traditional Hopi music, Conlon Nancarrow or examples from traditional Japan, but this wasn’t the intended point. Pogoroloffsky’s contribution adds a systematic bent that might encourage & enable musicians to more deliberately cultivate time in new ways in their own work. While these ideas may not at all be “new” (& how much really is?), there’s plenty more to do with these possibilities for those of us who are breathing right now.