Morandi at CIMA

Christine Hughes

November 2015

Giorgio Morandi, Roses, 1917, Oil on canvas, 58 x 50 cm.

Giorgio Morandi, Roses, 1917, Oil on canvas, 58 x 50 cm.

When I was 13 and just finishing my catechism classes, having been newly confirmed into the Catholic Church, I was asked what I wanted to do when I grew up. I replied without hesitation that I wanted to become a monk, one who took the vow of silence and was a mendicant. I was told just as quickly in response that because I was a girl I could instead be a nun. This is when I became an artist.

Giorgio Morandi has for me always been an artist whose work I turn to for inspiration, guidance, and to renew my vows, as it were.

We have so few opportunities in the United States to see an exhibit of Morandi’s work.

The Center for Italian Modern Art on Broome Street in New York City has just opened a fine exhibit, Giorgio Morandi, which runs through June 25th, 2016. CIMA is a non profit research and exhibition center. On Fridays and Saturdays their fellows in residence give a guided tour of the exhibit (as well as a wonderful espresso prior). The viewing that I attended was peopled mostly by artists (mostly established), who I would bet we’re there for the same reason I was.

Giorgio Morandi looms large in legend. Exaggerated claims of his lifestyle; not traveling, not allowing anyone into his studio and being uninterested in fame or fortune.

He lead an exemplary life in that he seems to have made all his decisions based on his relationship to his work. He did a bit of travel, saw and appreciated the work of Cézanne, Giotto, Piero della Francesca and other artists, yet was basically content to stay in his family home with his sisters and keep the focus in his studio. Some exaggerate his steadfastness to extremes. I disagree with that characterization. Any artist knows when they come to that point in their work where something spiritual happens it’s a gift. We know not to leave the room, not to let anyone disrupt us, to forget about dinner and so on. The more we work, the more these times happen. I do think that Morandi was living his life pretty close to that state all the time and he was very protective of it, nothing more than that.

Morandi himself destroyed most of his early work, his juvenilia. In this exhibit the earliest painting is from 1916 Bottiglie e Fruttiera with a fresco-like surface and a palette near Giotto’s. There are a couple of paintings from 1917-19 which were done during Morandi’s short lived involvement with the Italian art movement Pittura Metafisica and his comradeship with the painters Carlo Carrà and Giorgio de Chirico. On the verso of Cactus is an early self portrait done during this period in a manner reminiscent of early Léger discovered during the cleaning of the painting in preparation for the MET 2008 show. CIMA has a photo of this self portrait on hand and occasionally will show the verso.

Giorgio Morandi, Still Life, 1931, oil on canvas, 54 x 64 cm

Giorgio Morandi, Still Life, 1931, oil on canvas, 54 x 64 cm

Morandi quickly made his own way developing his imagery of vessels sitting upon a surface, some which he painted on the inside, some on the outside to achieve his preferable colors and also to dull the surface so his light would drag across instead of racing. The atmosphere is palpable in all his work. We are breathing the Italian air, the dust from the war settling on some of the vessels. He was constant in all, working the same objects over and over in each painting, drawing, watercolor and etching sometimes placing a few more or less and starting a new work. One can dip into Morandi in any painting and come away with the sense of everything he did. His entire oeuvre coming through in the one piece. Magic, similar to looking at a Giacometti and not seeing but sensing all the layers of painting and scraping away, and painting again no longer visible but none the less there.

Giorgio Morandi, Still Life, 1931, oil on canvas, 42 x 42 cm

Giorgio Morandi, Still Life, 1931, oil on canvas, 42 x 42 cm

Many of the paintings in the show were done in the 1930s culled from the collections of Gianni Mattioli (whose daughter Laura Mattioli is the founder and president of CIMA) and Augusto Giovanardi who were both collectors and friends of the artist through out his life.

The 1930s is an interesting decade in Morandi’s work. It was a decade when he was finding his voice and made fewer paintings than at any other time. He was teaching etching at the Accademia di Belle Arti. Italy was under Fascist rule. A lot of art in Italy at the time was political and about spectacle, not particularly personal. Morandi deepened his palette to browns and darkened earth-tones, working slowly, also deepening his gaze inward. Seemingly the political darkness made it way into his work. It was during this period when he honed his approach to his personal style of applying thicker paint and becoming more poetic with his forms and less representational.

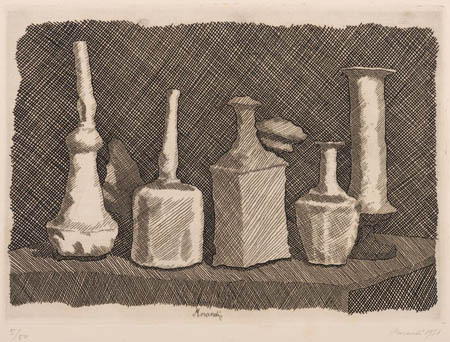

There are several etchings from this decade which show Morandi’s mastery of line in the dense black of printer’s ink.

Giorgio Morandi, Natura morta a grandi segni, 1931, etching, 24.5 x 34 cm.

Giorgio Morandi, Natura morta a grandi segni, 1931, etching, 24.5 x 34 cm.

In the last gallery of the show there are six paintings from the 1960s, the last decade of Morandi’s life, in which his imagery seems to be dissolving into abstraction, or is condensed into fewer objects, air and paint mingling on the paintings surface.

CIMA has included four contemporary artists whose work speaks to or compliments Morandi’s work. Three of them are photographers who had the opportunity of working in Morandi’s Bologna studio.

Joel Meyerowitz’s photographs of the vessels used by Morandi in his still lifes are singular and centrally formatted. It appears that each object was in the exact spot in every photo, the lighting and camera remaining stationary, creating a shadow running to the right and back. These photos are quite large compared to Morandi’s paintings (each 16 x 20 inches) and have a dusky, painterly air. An homage to Morandi, gazing into these objects, their scale and singularity making them iconic. It is as though we are seeing them through the gauze of time, but larger, like an image in the mind’s eye after a long meditation on it. I was interested in the distance between the artistic photograph of the object and the very subtle quality of the same objects in a much smaller and quieter Morandi painting. There is a huge difference; similar to looking at a photo taken from the exact angle and location where van Gogh stood and painted, and the painting done there. In that gulf one clearly sees what art is.

Matthias Schaller has done a photograph of Morandi’s Palette also large in scale. The palette has a surface of mottled colors which seems impossibly beautiful.

When Morandi set up a still life he marked the paper surface of his table to indicate and notate the placement of each object. It seems he used the same paper for a long time based on the numerous markings. Tacita Dean made a film based on this. The CIMA exhibits six photo stills from her film. The prints are black and white and have enlarged Morandi’s subtle markings to a scale which reminds one of the Surrealists’ “automatic drawings.”

The Wolfgang Laib sculpture Schiff made of honeybee wax has a similar sensibility to Morandi’s work, its waxy patina reminiscent of a painted surface. The piece has a warm presence. It is visceral, soft edged, earthy and silent.

Giorgio Morandi, Still Life, 1963, oil on canvas, 26 x 26 cm

Giorgio Morandi, Still Life, 1963, oil on canvas, 26 x 26 cm

The Center for Italian Modern Art is an elegant and relaxed environment in which to view the exhibition. In Italian style while minimally furnished, it allows for sitting in the galleries and the kitchen. The fellows who guided us through the exhibit had a deep knowledge of the material they were speaking about. It was an added pleasure to hear it in an Italian accent.

All images courtesy of the Center for Italian Modern Art

I have never appreciated Morandi’s work more than now, after having read your essay. Thanks for sharing your thoughts, my dear and amazing friend.

You introduced me to Morandi’s work years ago, and I feel I can’t get enough of it.

I have to go!

Polly

Hey Christine,

Nice essay, powerful story of your own beginnings as an artist.

So glad to learn of this artist and his inspiration for you. I can see the influence in color and form and love the natural sphere into which you have brought this way of seeing. Thank you for enlightening me.

A painters appreciation of Morandi. Thank you for your words.