Marcel Duchamp, Fountain: An Homage

Ron Morosan

May 2017

Pamela Joseph, Censored Small Fountain by Duchamp (Tan), 2014

Pamela Joseph, Censored Small Fountain by Duchamp (Tan), 2014

close-up image courtesy of Arteidolia

Francis M. Naumann Fine Arts is having a 100th anniversary Happy Birthday exhibition for one of the most famous works of art that was never exhibited: Marcel Duchamp’s urinal titled Fountain, which was rejected by the directors of the Society of Independent Artists’ first annual open invitational exhibition, which promised to exhibit all works of art as long as they were accompanied by a six dollar entry fee. This historic exhibition opened on April 10, 1917 at the Grand Central Palace at Lexington Avenue and 46th Street, New York City, but a few days earlier the painter George Bellows argued with Walter Arensberg demanding that Fountain, submitted by Richard Mutt, be excluded, and excluded it was. The story became legendary and Fountain became one of the groundbreaking works of Conceptual Dada and one of the most recognizable works in the history of art.

Naumann has titled his exhibition Marcel Duchamp, Fountain: An Homage, which suggests Duchamp’s spirit of tongue in cheek humor in which Fountain was originally presented. Walking through the exhibition it becomes clear that serious avant-garde business is going on, exclaiming the tremendous importance Duchamp’s work has had on the history of modern and postmodern art. At the same time, this exhibition is filled with humor, so much so that on first entering the gallery this writer smiled and almost laughed out loud.

Duchamp was no doubt one of the most brilliant artists of the twentieth century, and perhaps the most remarkable theoretical thinker since Cézanne. However, at the same time, he was a great humorist, if that word fits, and in a sense it doesn’t, because humor was a serious business for him as well. He is reported as saying: “Humor is very important in my life, as you know. That’s the only reason for living, in fact.”

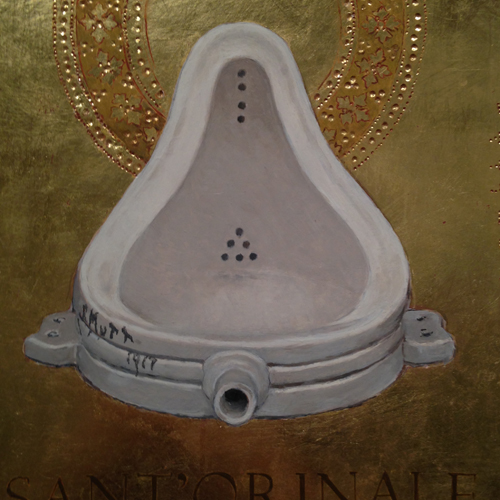

Kathleen Gilje, Sant’Orinale [Saint Urinal], 2017

Kathleen Gilje, Sant’Orinale [Saint Urinal], 2017

close-up image courtesy of Arteidolia

In the large front gallery, Kathleen Gilje’s Sant’Orinale”(Saint Urinal) is one of the perfect paradoxes of humor and grace in the exhibition. Beautifully painted in traditional thirteenth century gold leaf over bole ground, it captures the official portrait of the Mutt urinal in a form that only high Classical painting can impart, but at the same time this Classical reverence is Monty Python-like, an absurd praise through physical material, showing how sheer beauty of material presence can be enough to convince; it is hilarious in its dressed-up sainthood.

In Peter Saul’s Urinal Descending a Staircase, (Its title alone is a hoot.) floppy multi-colored urinals descend a clunky wooden staircase and could have served as a newspaper cartoon of 1917, had everyone known that Duchamp was the author, and not Richard Mutt.

Peter Saul, Urinal Descending a Staircase, 2017, close-up image courtesy of Arteidolia

Peter Saul, Urinal Descending a Staircase, 2017, close-up image courtesy of Arteidolia

Tom Shannon’s row of wearable neckties displayed behind the reception desk is a wry commercial twist on the pattern of drainage holes in the original urinal, a pattern very distinct with four holes at the top and a pyramid of seven holes at the bottom. Not all the urinals on display have this distinctive pattern, but maybe a urinal is a urinal and that is all there is to it.

There are urinals that closely resemble the original Fountain like Sturtevant’s Duchamp Fountaine of 1973, an official appropriation piece, as is Sherrie Levine’s gold plated Fountain (After Marcel Duchamp), Madonna of 1991. The effect of seeing so many urinals on display in a gallery space is very humorous, and reminds one of a scene in the Mel Brooks’ film The Producers, shot from overhead, of auditioning actors trying out for the role of Adolph Hitler, all wearing the mustache and saluting “Sieg Heil.”

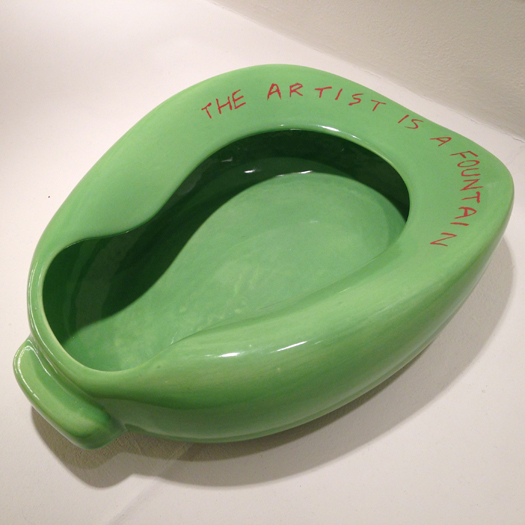

There are also a number of urinals or abstracted urinal-like pieces in this show that are not humorous at all. Among them is John Baldessari’s hospital bedpan titled Repository and inscribed with the sentence: The ARTIST IS A FOUNTAIN with the apparent point of proving again that Conceptual Art is a cerebral act. There are two other artists who show very enigmatic pieces that indicate a lot of considered thought went into them. Don Joint’s UrinaL is an odd work consisting of a framed rectangular panel enclosing an ochre colored “L” collaged in the middle. Scratched and containing suspicious substances and a name tag hanging on the left side, this work offers a personal cerebral take on Duchamp’s Fountain. In the back gallery on the right side wall, is one of the most curious and disturbing works in the show: four photographs of a large outdoor wood house-sized urinal-like structure made by Saul Melman. The photos and accompanying narrative explain that the artist wanted his fountain to resemble a gallery with classic proportions and a water fountain in the center with deodorant cakes like those found in an actual mens’ room urinal. An extreme reaction is everything in this work, with the grand finale of moving it to the Burning Man Festival and lighting it on fire!

John Baldessari, Repository, 2002, close-up image courtesy of Arteidolia

John Baldessari, Repository, 2002, close-up image courtesy of Arteidolia

The act of censoring becomes a theme in a few of the works on display including Pamela Joseph’s painting Censored Small Fountain by Duchamp (Tan), a realistically painted view of the Mutt urinal which has the upper area, where the drainage holes are located, censored out by the digital rectangular grid we are all familiar with. In Mike Bidlo’s bronze Fractured Fountain (Not Duchamp Fountain 1917) we are presented with an accurate version of the original Mutt fountain, but it has been smashed and then glued back together and cast in bronze, as if to give it permanent objet d’art status. Censoring is indirectly present in Caroline Bachmann’s small painting Around Fountain in which she has reproduced the area surrounding the background of the Stieglitz photograph, which is actually a Marsden Hartley painting The Warriors, leaving the image of the urinal blank, thereby censoring the urinal with absence.

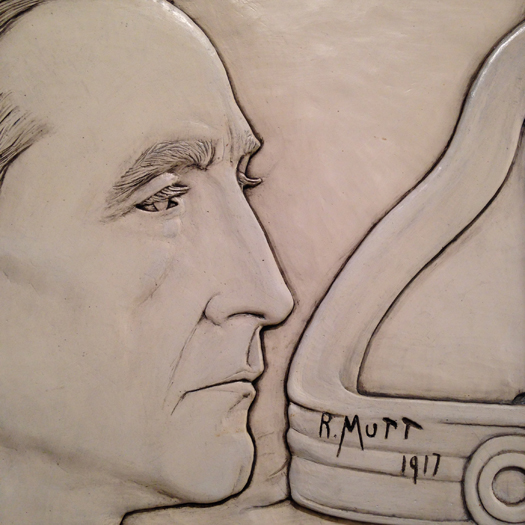

A nonobjective response to Fountain can be found in the work of Tom Hackney; he presents a vertical rectangle of white painted aluminum about two feet high with two sets of circular holes at the top suggesting an official emblem commemorating Fountain, then titling it with the word Vespasienne, giving it a clever Parisian pissoir historical connection. A similar act of commemoration is going on in Jonathan Santlofer’s Portrait of Richard Mutt, a bas-relief carved hydrocal three quarter profile of Duchamp next to half of the R. Mutt’s urinal, a presentation of evidence that this is the true author of Fountain, and it will be officially recognized, as in the publishing of a commemorative coin or medal.

What would a birthday party exhibition be without a cake? Even that is provided, and very well done, by Sophie Matisse. Her Urinal Cake constructed of meringue bricks and white icing, is an accurate and well modeled version of the R. Mutt original, although missing the signature. Given the abstruse story surrounding Fountain, presence and absence are a subtext running through this collection of multifaceted responses to a brilliant strategic joke that reveals an interchangeable truth about the creative act and the scale and ideological scope upon which that act can operate. Fountain was submitted by an absent proxy artist and then the submission was rejected and not in the Independents’ exhibition, another absence. Then, in the May, 1917 issue of P. B. T. The Blind Man, the magazine published by Duchamp, Roche, and Beatrice Wood, the urinal story and its rejection is recorded; this is a presence. The artist Mutt is a presence in the name of a character in the Mutt and Jeff cartoon strip popular at the time. Then the actual R. Mutt urinal disappears completely and it, or its proxy, appears in photographs, once in the Sidney Janis Gallery and then in the studio of Duchamp: again presence is shown.

Duchamp was cunningly aware of the effect his urinal would have. His choices of subject, his working and not working, his involvement and non involvement in art all point to a brilliant strategist. Somewhere in that extraordinarily astute personality was a very good lawyer who understood that art was a consequential contract.

Jonathan Santlofer, Portrait of Richard Mutt, 1996

Jonathan Santlofer, Portrait of Richard Mutt, 1996

close-up image courtesy of Arteidolia

Marcel Duchamp, Fountain: An Homage

Francis M. Naumann Fine Arts

24 West 57th Street, Suite 305

New York, NY 10019

April 10 – May 26, 2017