Leave Nothing Out

patrick brennan

March 2016

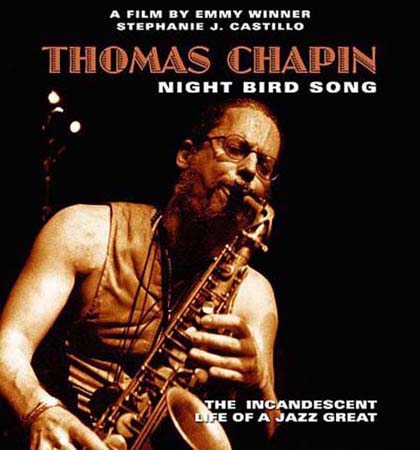

Stephanie Castillo’s Thomas Chapin, Night Bird Song: The Incandescent Life of a Jazz Great

Wow. Journalist and filmmaker Stephanie Castillo has accomplished a combination coup and tour de force with her documentary on the music and life of composer–saxophonist-flautist Thomas Chapin (1957-1998). Chapin was a master musician willing and able to crisscross assumed genre boundaries whose intensive activities were interrupted at the age of 40 by a sudden intrusion of leukemia.

Why the wow? Well, representing a person’s life, actions and impact is some pretty delicate stuff, especially in our hyper-networked, post-literate media’d condition. Filmed image plays proxy for once upon a time realities, once real, now gone, lingering now only as virtual visage. Once we had storytelling that turned legend and, more recently, the photograph — which, by the way, is all we’ll ever have of Buddy Bolden. Recordings have since then intervened. Beyond that, film might offer the closest approximation of what it may have been like to be there witnessing the actual smells, uncertainties, reactions and surprises, the real flavors that inform the possibly opaque meanings behind a music’s sounds: its context. As for our imaginings of an actual artist, such doubles depicted in light may introduce a persona at once more memorable and almost appallingly different from who that artist really was, and this displacement may instead be the one that overwhelmingly endures and recreates itself.

Stephanie Castillo not only calls upon her 30 year experience as a documentarian to portray a Thomas Chapin consonantly familiar to those who still remember him like yesterday, she concurrently details the cultural milieu(s) within which he operated, environs now potentially as cryptic as the Neolithic for those who’ve grown up from the start amid cellular communication. The variegations of Chapin’s own musical adventures window for us insight into the explorations of an entire community of musicians at the time; and the filmmaker manages to encompass the historic, the personal and the intimate without succumbing to variations on the cult of personality, seemingly a paradoxical balance in a film so heavily organized around personal recollection.

Chapin exuded no shortage of personality, but his own attention consistently focused on music sans self aggrandizement or display. The music had found him, and he’d taken on the serious work of keeping up with it. That’s what he was all about. Accordingly, Castillo could bypass stock images of the hero, the great master, the victim, the star, the unjustly neglected artist, the celebrity, the sage, the cultural icon, the human face on the historical compass, etc. to achieve another tone, a great deal of which grows out of a commitment to let the music itself do so much of the talking. There’s abundant performance footage here, including an uninterrupted, beginning to end rendition of his composition Night Bird Song by the Thomas Chapin Trio at the 1995 Newport Jazz Festival.

As film, Night Bird Song flows with remarkable fluidity. Its two & a half hour duration slides comfortably by. There’s no fluff, no gratuitous filler; and I suspect that, even with the additional hour of the director’s cut, it would still feel the same. Castillo drew on a patchwork of performance clips, 47 different interviews, home movies and videos, photos, images of performance programs, posters, album covers — all of which seamlessly coordinated, their colors and values well orchestrated throughout. The timing feels flawless. It should come as no surprise that the editing process alone consumed eight months of full time engagement. This is a superbly assembled work.

That’s the tour de force. Where’s the coup? As far as “jazz memory” goes, so called “canons” and all that, Thomas Chapin is (and was) a pretty marginal character — not at all to the people who knew him and/or his music, but his impact and presence were never exactly “mainstream.” Why make a film about someone like that? For one thing, every person whom Castillo asked whether Chapin’s life and work were really worthy of such attention responded emphatically with a “yes.” That “yes” refers both to his music and his character as well as to a life thoroughly and well lived. Castillo’s film goes even further to make an argument that Chapin deserves recognition as both an important part of the tradition and of potential futures for music. She also implicitly opens questions around who really decides these things and invites viewers to decide for themselves.

Usually documentaries of this scale have been made about artists after they’ve already achieved a certain level of recognition and validation, but there are also historical considerations to add to this perspective. One of these is of course the growing decentralization and relative affordability of filmmaking. The other is the nature of “acclaim” for most of those called “jazz musicians” who were born after 1950.

Chapin, like other Americans born in the ‘50s, lived across a particular series of historical breaking points and discontinuities, arriving at technical adulthood just in time for the New Deal’s egalitarian legacy to fissure. Meanwhile, the music nicknamed “jazz” had succeeded to an old growth forest climax community never to be witnessed again. Ornette could sing Happy Birthday to Louis Armstrong. Roy Eldridge might be playing just down the street from Pharoah Sanders within complete and conscious earshot of each other: and reformulating the innovative achievements of earlier generations into prescribed limits to abide by and imitate — as did the still younger Lincoln Center neoconservatives of the ‘80s — was, as yet, still unthinkable.

While it was still possible for a very young musician to shake hands with Duke Ellington after having witnessed his music live, there also remained opportunities for the very capable to actually work with and learn first hand from some of these landmark predecessors. Chapin, after studying with Jackie McLean and Paul Jeffries, was mentored into a position in Lionel Hampton’s big band, and, after a while, even became that group’s musical director. He was thereby gifted with the opportunity to expand upon and develop in situ his understandings of Illinois Jacquet, Jackie Mac and James Spaulding, of the blues shout and its necessary gestures of affirmation, ascendance and transcendence. Chapin aspired no less to, in Monk’s words, lift the bandstand, and Hampton’s examples of showmanship and audience communication were instructive in this regard. This solid and empathetic rooting in African American reciprocalist aesthetics and techniques distinguished Chapin’s contributions to the eclectic Knitting Factory scene from the rock and punk approach to energy that relied more on force, unanimity, mass and pumped up amplitude.

Chapin’s world travels with Hampton introduced him to person to person contact with musicians and music from all over. As he eased himself out of his commitment to the big band, explorations of Latin American music especially drew his attention; but Chapin was also a full spectrum player who had all along been aware of, and active in, experimental musics as well. He was a musician to leave nothing out. Like Don Cherry, Thomas Chapin could contribute to any musical context and still resonate sonic and personal identity. You always knew who was playing wherever you heard him.

While working himself into the NYC musical arena, Thomas was still able to rely on nearby musical connections and collaborations in his native Connecticut, activities that he sustained throughout his career. But, to carve out a niche as an individual sound and concept and apply that as a leader levies more than its weight in challenges. The financial security of a regular gig with Hampton had for a while helped cushion him from the accelerating effects of the “J” word’s having become more and more a pariah among the major labels, whose recordings had formerly helped many performing musicians develop reputations that further expanded their possibilities of working. While DIY production (dating back at least to Mingus & Roach’s 1952 founding of Debut Records) had already earned a distinguished history as an exercise of self determination, for Chapin’s generation, in place of offering another option, DIY often posed the only available recourse.

However, new opportunities emerged in 1987 on E. Houston St. in Manhattan at the innovative Knitting Factory, which operated as a magnet to many of the artists paying those do it all yourself dues. It opened its door and roulette wheel for experimental and fringe musicians of all sorts, whether related to jazz, funk, rock, euroclassical, world fusions or the unclassifiable. Some musicians walked away feeling swindled; others treaded water playing to mysteriously empty rooms; and some found themselves lifted into the epicenter of a propulsive new scene.

Record store hero Bruce Lee Gallanter heard Thomas with the high energy, free form electric group Machine Gun and recommended him to the Knit’s founder Michael Dorf (who’s also, to his credit, a coproducer of this film). Not only did Chapin’s own band turn heads, Dorf soon after elected to feature his trio on the very first issue by the new Knitting Factory label. The Knitting Factory came to signify a new brand of musical adventure, eclectic and defiant of genre stereotypes; and the cachet of that image led to Knit sponsored tours in Europe — and even in the U.S., all of which helped put Thomas’ music on the map and sponsored the more ambitious development of his compositions for larger ensembles.

Thomas Chapin’s freewheeling aptitude and appetite for going anywhere musically contradicted the aggressive balkanization being promulgated around the moniker “jazz” in the ‘80s and ‘90s (to a great extent a closet limited resource fight over who gets to make a living in music) that pitted the neoclassical stylistic prescriptions forwarded by the Marsalis contingent versus the more inclusive process orientation of the AACM and other so called “downtown” New York musicians. For him, such distinctions were meaningless. And he was right. His approach to any musical material, “traditional” or unforeseen, never turned itself retro because he actually heard everything anew in and for in the present.

If he had been favored to live longer, not only would he have further matured and developed his evolving musical conceptions, his persistence and musical persuasiveness would eventually have worn down the barriers of the bogus style wars, and his work and example would indeed have emerged as more recognizably central to the evolution of music as we live it.

Film Screenings at Real Art Ways, Hartford, Connecticut, Sunday, March 6 & SVA Theater, 333 W. 23rd St., NYC, Sunday, March 13

For more information visit:

The Thomas Chapin Film Project

http://www.thomaschapinfilm.com

I am honored for your lovely and insightful review, Patrick. You got me, the film and Thomas! Beautifully expressed, with warmest regards, Stephanie J. Castillo, the filmmaker

Patrick,

Fantastic movie review. I am still feel the impact intensely of the Chapin story and the infusion of his creative spirit he told through his music.

Thomas or (Chap) as we called him in Ct. never failed to provide me with musical nourishment when ever I heard him. When I moved to NYC and was able to collaborate with him it validated my decision to live here.

Good to see you again and let’s stay in contact.

Michael

patrick

A brilliant piece of writing!

Thanks,

mario

Patrick, thanks to your review, I must see the film. Your article did more than describe the film and and the music and life of Thomas Chapin. It placed jazz and critical thought into a context of the late twentieth century. It also described a significant contribution by an artist who was not necessarily mainstream or a household name, but one who certainly deserves our attention. Thanks again, Alonzo