Koho Yamamoto: Under a Dark Moon

Ivan Klein

July 2021

Dakin Hart, the head curator of the Noguchi museum, in his introduction to the exhibit, Koho Yamamoto: “Under a Dark Moon” *, notes the artist’s deep association with sumi-e (black ink painting) and the veneration in which she is held as a teacher of this ancient Japanese art form. He asserts that “Despite, but more truly because of, her close association with that tradition, she is almost entirely unrecognized, even among her greatest admirers, for what she is: a great postwar abstract painter.”

— Hiding in plain sight, as it were.

He sees the black paintings on display “as steady visions from the psychic vacuum of the unknown” while emphasizing the influences of the downtown artistic milieu to which she was exposed while at the Art Students League in the late 1940’s.

Perhaps most tellingly, Hart writes that her work stands atop the [sumi-e] tradition, but is not contained by it.

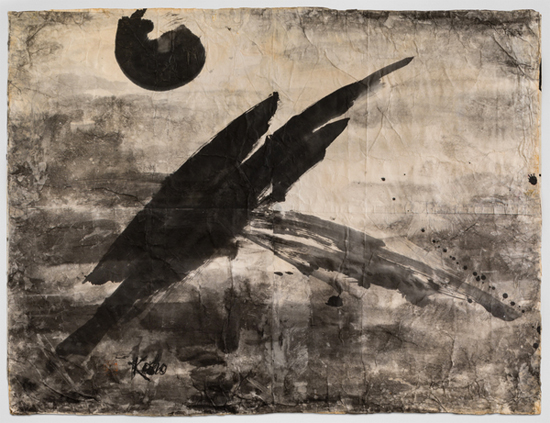

Untitled, 1987, Ink on paper. 34 1/8 x 44 1/4 in.

Untitled, 1987, Ink on paper. 34 1/8 x 44 1/4 in.

Collection of the artist. Photo: Nicholas Knight

A perfect sumi-e circle indicative of superior artistic and spiritual power boldly intruded upon, becomes

a fractured Black Moon

peeking just above

no end of pure chaos

Untitled, Ink on paper. 2 3/4 x 5 5/16 in. Collection of the artist. Photo: Nicholas Knight

Untitled, Ink on paper. 2 3/4 x 5 5/16 in. Collection of the artist. Photo: Nicholas Knight

Are those white clouds

pierced by stabbing black

mountains of sorrow and doubt?

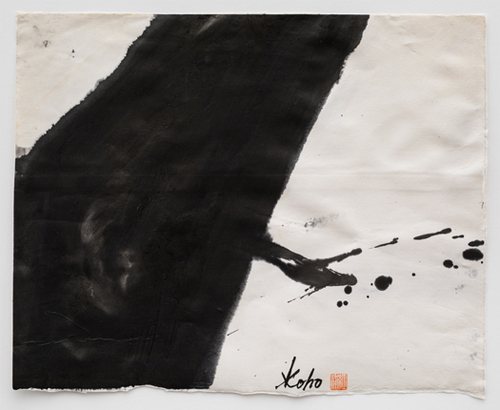

Untitled, Ink on paper. 16 x 20 in. Collection of the artist.

Untitled, Ink on paper. 16 x 20 in. Collection of the artist.

Photo: Nicholas Knight

A volcanic eruption

with the Master’s

feathery touch

Untitled, Ink on paper. 37 3/4 x 73 3/8 in. Collection of the artist. Photo: Nicholas Knight

Untitled, Ink on paper. 37 3/4 x 73 3/8 in. Collection of the artist. Photo: Nicholas Knight

If Jackson Pollack’s inspired drips are worth nine figures,

what I ask should this spontaneous jazz masterpiece be valued at

by a still uncomprehending world?

· · ·

In her review of the exhibit for the “Brooklyn Rail” (May ‘21), Amanda Millet-Sorsa comments on “…the sense of healing materialized through her use of the ink and the vibrations of her simple yet complex gestures.”

Healing Qualities

In these paintings, clearly selected from the artist’s darker side, Ms. Sorsa manages to discern that healing and restorative function which has made Koho the beloved sensei (teacher/spiritual guide) to legions of students and admirers. Now in her one hundredth year, still giving classes and creating, she continues to radiate these qualities. [Full disclosure: I am a friend and neighbor of the artist and have written about her work previously].

I interviewed Ms.Yamamoto in her apartment on June 9th and asked if she recalled any lasting influences from her time at the Art Students League in the post WWII years. In her mid-twenties, at that time, but not long removed from the closed environment of the American concentration camps in which she had spent the better part of four years, she mentioned her shock at seeing her first nude model and said she gained the ability to draw the human face and figure during her time there.

I questioned her specifically about the influence of the Abstract Expressionists, and she cited Franz Kline as someone whose work she admired. His art bearing an obvious resemblance to Japanese calligraphy and sumi-e as noted by the critics, but denied by him as direct inspiration.

As to the impact of the abstract expressionists in general on her work, her answer was not definitive. My own feeling is that she was, as we say, in it, but not of it, although she certainly expressed strong feelings abstractly on crucial occasions. — A brilliant modernist painting flecked with red ink that she did after she was informed in 2010 that the lease on her now legendary MacDougal Street studio was not being renewed and took a bad fall outside its entrance.

But also produced the figurative “Firebird” a few years earlier, following serious illness with the same sort of emotional impact.

The shock of Hiroshima and Nagasaki as well as the experience of extended incarceration on a sensitive young girl such as Masako Yamamoto, can’t be minimized. Yet sumi-e is a spiritual art, and this modest woman with a steely will is a true master of all its facets.

Takuin (late 16th c.):

The compassionate heart with

The frosty wintriness of an

unbending spirit

D.T. Suzuki in his classic Zen and Japanese Culture comments on the mid-17th c. Hagakure (Hidden under the Leaves): “…it states that no great work has ever been accomplished without going mad — that is, when expressed in modern terms, without breaking through the ordinary level of consciousness and letting loose the hidden powers lying further below…When the unconscious is tapped, it rises above individual limitations.” — The essence of modernity as well as (in its own peculiar way) the spirit of Zen.

In Koho’s words, her “painting coming from nothingness [that] sometimes…successfully emerges in the spirit of the moment.”

I am left with the memory of Koho in the Noguchi Garden on a perfect day in May. The garden, a masterpiece of Zen simplicity with its ancient multi-limbed tree and stark white stone on a pebbled field, the artist seated beneath a great shock of bamboo surrounded by friends and admirers. Nothing could be finer.

* See the Noguchi Museum website for the full text of Dakin Hart introduction →

Koho Yamamoto: “Under a Dark Moon”

10 Untitled works on paper from the artist’s personal collection

Exhibition at the Noguchi Museum 3/10/21 – 5/23/21 →

◊

Ivan Klein published Toward Melville, a book of poems from New Feral Press, in July 2018. Previously published Alternatives to Silence from Starfire Press and the chapbook Some Paintings by Koho & A Flower Of My Own from Sisyphus Press. His work has been published in the Forward, Urban Graffiti, Otoliths, and numerous other periodicals.

Other essays, reviews and poety by Ivan Klein on Arteiodolia→

For information on Ivan Klein’s latest book

The Hat and Other Poems and Prose from Sixth Floor Press

click here →