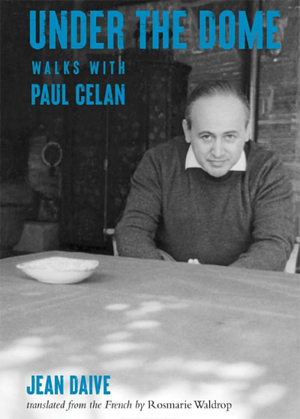

Jean Daive’s Under the Dome: Walks with Paul Celan

Ivan Klein

October 2021

Under the Dome — Walks With Paul Celan

by Jean Daive, trans. by Rosmarie Waldrop

reissued City Lights Books 2020

“We are walking and the shade of the trees covers us with a dome wherein we move and wherein we direct our words.” — Jean Daive

The distinguished translator Pierre Joris’s virtual talk on Celan in March of this year zoom-bombed by Neo-Nazis. The Forward, in its article on the event, asks its readers what they thought the poet’s reaction would have been. I believe he would have understood it in the context of his reading at Bonn University in November 1958. There, in real life, a student circulated a cartoon of a slave in chains and a parody of Celan’s poetry. The need to deface, distort words that expose things as they are. — A symptom of a malady for which no remedy has ever been found. Primo Levi, released from Auschwitz, walked the streets of Munich looking into the faces of the people: “Still capable of hatred and contempt, still prisoners of their own tangle of pride and guilt.”

__________________

Beset by psychological and emotional difficulties, Celan threw himself into the Seine off the Pont Mirabeau in the Paris spring of 1970 at the age of 50.

Apollinaire:

Neither time that is gone

Nor love ever returns again

Under the Mirabeau Bridge flows the Seine

A terrible harvest of suicides of the literary men of the Holocaust. — Primo Levi and Jean Améry among others. Difficult to draw broad conclusions. Each man’s soul unique. If there is something beyond individual circumstances, I suspect a certain kind of brokenness of spirit, a base humiliation that the Nazis specialized in that was profoundly difficult to shed. This along with unappeasable memory and pessimism as to the future of the very day and its unfolding.

But let us look at Paul Celan as Jean Daive portrays him in the years before his end, as they become acquainted and decide to translate each other’s work: Celan’s poetry into Daive’s native French and Daive’s far less established work into Celan’s acquired German.

Celan had been hospitalized for psychotic episodes, attempted suicide and carried an unsupportable burden of guilt toward his family in Romania from the war years. Perhaps not least, he was aware that his new young friend, Jeah Daive, was sleeping with his estranged wife, Gisèle. Daive: “And how did this immediate triangulation happen so naturally? Paul—Gisèle—me?” (Daive 25, Gisèle 43, Celan going on 50.)

Daive: Gravely he steps toward me, “What has happened?” The reply is not given in Under the Dome and may have been unanswered and unanswerable as the two mostly avoided it on their “walks.”

Walking with Daive and staring at a pond near the Ecole Normale, Celan says, “Autobiography is a goldfinch . . . ” and watching a trained monkey perform with a group of gypsies, “Don’t you think a drum is a bit like a mother’s heart?” — Somehow, I take both these remarks to be signs of a lingering bad conscience.

Fuzzy French metaphysics and despair in which the great poet of the Shoah is about to drown. — More correctly, has already drowned. — Daive’s vantage point being that of melancholy retrospective. Celan can’t find le mot juste with which to translate Daive’s enoncé — statement/declaration. Just can’t find it. A kind of fetish is what it turns into.

Thorn: “The camp [Romanian work camp to which Celan was consigned] . . . also the sun.” — This last should have been truly alarming. — Life itself, planetary life, the air we breathe proving nothing more than a gaff. — How could Daive, a person on the make, possibly comprehend or empathize?

The actual conversations between the two men both real and unreal — tending toward the symbolic and gestural. A flimsy dividing line separating the various realms of thought and feeling. — Celan, with that lower lip of his quivering, seems always on the edge of disintegration. And it must have been someone who experienced the same vacancies who dreamed up the topography of Hell with its infernal rivers and tiers of agony.

There are what could be termed dream conversations between them. In one such, Celan accuses Daive of hiding his transitive God up his sleeve. Daive pleads innocent and then wakes up. Certainly, during all his fully awake conversations with Celan there is the whole business with Gisèle to somehow keep from spilling out into the open.

Under The Dome —

Daive: “You mean gold rises to the surface, Paul Celan?”

“Yes, this kind of gold surfaces like memory. Everything surfaces. Everything doubles, of course, the hand and the spade, but the hole is for you and me.” Double trouble we could say. — Memory plain and simple. — Or not so simple.

Walking beneath that canopy of trees (the Dome). Aren’t those gentlemen really strolling through that private hell of Celan’s? — A horrifying accusation that screams a silent “guilty” through the refracted air of Paris. — Oblivion and silence in their essences. The mysteries that lie beneath this umbrageous dome that canopies their strolls, dialogues, dreams.

__________________

The two men have a favorite neighborhood eating place, Le Chope. They eat red meat there as if in masculine solidarity, as if the bloody fare can create a sturdy bond between them.

The Ring

Daive: “With Gisèle, the question of the ring comes up. Clenched hand. The ring resists.” — True insider’s knowledge. One is supposed to get that she is about to go to bed with him. Then: “Gisèle Celan who has taken off her wedding ring, runs into Paul in avenue Emile Zola. He immediately notices that the ring is gone. A few days later, I run into Paul at the Contrescarpe. His finger too is without a ring.”

There’s no doubt as to Daive’s backdoor knowledge here. Beneath it all is the swollen blackened face of the poet after he is fished out of the Seine in that last Paris spring of his.

“You know, man turns on man.” — This poor floundering artist, practically an invalid, with this young would-be hipster in tow.

They engage in conversation:

“He [Celan] thinks I am a scream of God. A searching growl. Vacillation. Slowness. Perplexity. Different reading.” Daive says to him, “But a scream can burrow into a wound and scar. A kind of saliva, basically, that attenuates the pain.” — This neither receptive nor helpful in any way. Rather, it seems to me, to be insidious. — Simultaneously presenting and occluding the facts, the tragedy of the matter at hand.

Celan:

“I believe the scream is the chosen stance of a voice evicted from itself, mortally wounded, silent, terribly, become non-instrumental from being dispossessed, blank. A drunken voice, crouching. That regards no one . . .”

A mannered stance? — Surely, he jests.

Daive (innocuously):

“A geometric scream.”

And poor attitudinal Celan taking everything in his field of vision personally. Like that woman he sees on a street in Berlin making a fuss over a stray dog that has been run over. Yes, that poor creature meant more to that blessedly compassionate woman than the destruction of the Jewish people had meant to the German nation. No sense in emoting, taking offense, assuming a moral posture…

They stroll, the older man and the younger. An overwhelming sense of Celan’s personal loneliness. — What sort of intellectual and poetical tricks must he turn to keep his young companion attentive?

Celan reads on a wall in Paris in the late ‘60s that

“the dice won’t pass”

Both men are mystified by the graffito. Now, we can make a pass with the dice or pass the dice to the next craps shooter, but neither seems aware of le jou. — Celan says portentously that “The dice plunge, precede us, enact our fate.” Also, “Time plunges before us, always plunges in front of us.” Says in answer to Daive’s question that “It anticipates us.” — Little doubt that he is getting ready to take the plunge into those dark waters that were the mystery embodied. Making his point the hard way. Snake eyes is what we’ve got.

They stroll on, discuss memory. Winter in Paris. Snow falling. Celan imagines a man coming down in a white parachute. — Asks Daive to imagine it: “A man at the end of his parachute and of our immobile falling.”

Immobile Falling —

Does it mean falling without moving — tumbling helplessly through inner space? — Being frozen in one’s very soul?

At a certain point Celan seems to turn on Daive: “You are my torment.” — The truth between them, long suppressed, wells up. Later Daive calls Celan on the phone. Hears only sobs. Then calls Gisèle. Seeing her on the sly, he is the most compromised sort of intermediary.

__________________

Okay they’re walking again. That’s the subject of the book after all — their walks and talks. Celan raps on the strangeness of them as a pair of Parisian strollers. — Disparity as to age, differences in nationality, in their life paths. It doesn’t seem like such a big thing in retrospect. But the gulf that he creates in his speech, in his mind, is indicative of that which is close to the core of his illness. Alienated from most everyone he knew or thought hard about — wife Gisèle, Ingeborg Bachmann, his sometimes lover and friend, translators, whole races and nations. And deep and justified reservations about the young man Daive with whom he strolled, broke bread, shared what passed for philosophical observations.

The Jew / The Alien

the victim in contemplation / recollection

Nothing but doom in all this.

Life as a roll of the dice.

In the arts: Max Jacob: the surrealist Dice Cup

Sartre — Les Jeu Sont Fait,

Apollinnaire — “The Mirabeau Bridge”

Night comes the hour is rung

The days go I remain

— Celan contrived a radical revision to the above.

__________________

Celan to Daive: “How did you translate Heimat?” (hometown, homeland) — the ostensible purpose of the relationship — their translating each other’s work. — The question is Celan’s little paradox: “Heimat” — homeland — is untranslatable because to the exiled poet the word is a fabrication, an illusion, consumed as he is by his shady, tragic ‘Romanian Jew past. His guilt, shame, rage separates him from the very concept of a homeland.

A stepchild of the German language,

of the very Earth itself.

Like all real poetry, his was destined to come into being. Never mind the poor flawed vehicle that somehow fashioned it. Daive really puts it quite well, “This man chews his writing . . . This man confronts war because he was swallowed by the verb. This man, that is, the hangdog, the epileptic mover through a density of words from which the density is absent.”

Celan: “The subject includes the verb. The subject is the mirror of man.” — the whole poetic enterprise beyond any articulated approach, yet astonishes us by its very existence. — Sounds of despair dredged up from a seemingly bottomless void.

Celan: “We write with luminous wounds that illuminate our hands.” He speaks of piercing the Old and New Testaments with light and unifying them. — Messiah and Savior. — But what if the world just goes along in its regulation darkness and ignorance? — Those quivering lips of Celan’s are more and more in evidence during their conversations according to Daive, and it is obviously another very bad sign.

They walk. Flights of very shaky fancy from Celan. Daive answers with “Mmm . . .” — Really very cruel and parasitic, it seems to me.

Under the Dome —

No true shelter — A trembling naked psyche revealed. Difficult enough to stay alive in this world without carrying that witch’s brew of burdens that were his. — That cross of love and guilt and pariahdom and God knows what else.

A few seasons go by. Celan tells Daive that he has written to Martin Heidegger, the eminent philosopher and one-time Nazi enthusiast. “I’ve read much Heidegger. I’ve much annotated his books. I just wrote him. I don’t expect a reply.” Then, “I’m going to Germany. To meet Heidegger. I hope he’ll hear me.” Celan really means heed him, dramatically change his views on the war and, finally, repent.

Todtnauberg (Death Mountain):

The Great Philosopher hosts Celan at his Black Forest retreat and an elliptical record of the meeting exists in the form of Celan’s narrative poem “Todtnauberg”. — He drinks from the well with “the star die on top,” writes in the guest book

a hope today,

for a thinker’s

(un-

delayed coming)

word in the heart

When he returns to Paris, he tells Daive, “I had illusions. I hoped to be able to convince. I wanted for him to talk to me. I wanted to forgive. I waited for this: that he find words to trigger my clemency.” — It would be hard to imagine more naïve or quixotic ambitions. At any rate, no more “illusions” about the great German thinker with his pro-Nazi past and deafening post-war silence concerning what Celan referred to as “that which happened.” Illusions that were almost certainly seen by Heidegger as presumptuous, if not demented. Although it must be said that toward the end of his life, Heidegger did seem to feel a certain moral pinch. Hence his “Only a god can save us” in an interview with Der Spiegel. — We’ll call it a cop-out that Celan didn’t live to hear.

But after Todtnauberg, for the poet, illusions and presumptions vanish. — A decent starting point that somehow turned into a tragic ending.

Bad conscience/wrongs that we hide from ourselves, choose to ignore, rationalize. No one wishes to be reminded of what they already know too well. Least of all Heidegger with his very strongly held views along with those little nagging shadows that dogged him to the end. — His Jew mentor and friend, Edmund Husserl, given the cold shoulder when Heidegger was appointed Chancellor at the University of Freiberg in 1933 by the ascendant Nazi regime. “Only a God can save us.” Our sturdy arms, our impregnable intellects, our impervious souls all to no avail.

__________________

Celan’s literary biographer and translator, John Felstiner, quotes from a 1944 letter to a friend of his youth, Eric Einhorn: “There’s so much to tell. You’ve seen so much. I’ve experienced only humiliation and emptiness, endless emptiness.” Felstiner comments that “More nakedly than Celan would later do, this letter expresses the unimaginable losses that ground all his writing.” Ground, as in solid ground or no ground at all. The classic anti-Semitic trope of the rootless Jew with no country and no solid underpinning to his thought. Nothing beneath him at all. And it is that special sense of emptiness, the weight of those accusations and assumptions that are at the basis of Celan’s constricted and tortured words on his walks and talks with Daive. He tells him, “Yes, the poem should cross out the world. The poem is a diagonal that crosses out the world just as the syntax is the diagonal of the poem. Next time I’ll bring you ‘Todtnauberg’.” — If poetry could have truly cancelled humiliation, guilt, the world as it was…If words had the power to do more than words can do — if they were truly magic as they were primordially intended to be…

Celan and Daive discuss Kafka’s famous letter to his father. Mother, of course, knew better than to deliver it. Again, the tragic limitation. — Judgment passed on a level higher or lower than words. Consider the archetypal Father who judges but cannot be judged or known.

Under that shadowy dome, Daive asks who the father is in Letter to His Father. Celan replies that God is present and the judgment of men “and no doubt the misery of the son.” Often empty and tendentious, sometimes veering toward the truth is the dialogue between these two men. Celan with his need for companionship, Daive seeking guidance, although as Melville’s Ahab noted, there is a lower lay.

Did Celan think/dream of his father’s judgment from the grave upon him? — I believe he must have, with his ambiguous flight from his home in Bukovina just before the Nazis seized his parents and ultimately disposed of them. — Surely there was more than a bit of invention or confabulation in the story of his farewell to his father from opposite sides of a barb-wire fence. — and even the truest of sons doesn’t rest easy with whatever may be the judgment of his father’s shade. For sure, he doesn’t give himself a psychic pass, an easy slide out from under the weight of the fatherly verdict that so overwhelmed Kafka.

Gisèle tells Daive that Celan caused “a veritable scandal” at an official dinner in Berlin. One imagines how easy it must have been to set him off in that city. — All those oh so self-satisfied upper-class Germans arrogantly stuffing themselves. Celan had confided that after the publication of “Todesfuge” (Death Fugue) in 1952, there had been “a misunderstanding with Germany.” — Trashed, accused of plagiarism, yet he had written a great and defining poem that confronted Germany in its collective soul.

Still Another Stroll —

Daive tells Celan a surreal story of the literally shifting foundations of his childhood home. — Fissures in the floors, danger of falling into oblivion at all times. Daive, as a child, seeks refuge in dreams and fantasies while huddling under a sturdy wooden desk in an otherwise empty room.

“Basically,” sighs Paul Celan, “what difference is there between your imaginary games in a paternal desk and the spade with which I dig in a work camp? The password, most often unconfessed, is extermination and the idea is always the same: the ones who give life, order death.” — Celan fragile like delicate glass. — Also, on a hair trigger.

Paul and Jean sitting around one day doing the work of translating Paul’s work from German to French. Paul declares that man is without a verb. He is perhaps born of the verb, but he loses it. Life makes him lose it. — Aren’t we speaking of the total castration of Man and God? — And that terrible trembling of the lip — doesn’t it stand as a signal of his loss of the ability to act against a settled fate?

__________________

Daive claims that Celan’s suicide was unforeseeable, even though he had visited him during his psychiatric confinement at Saint Geneviève-des-Bois Hospital and knew the gruesome details of his attempted suicide, assault on Gisèle, the neighbor’s testimony as to his bizarre behavior. And we might add, his close proximity over several years to a man rather obviously in terrible psychic pain. Celan in conversation: “I have hidden the madness . . . my poetry masks the madness.” — Daive also professes to be surprised by Gisèle’s tears. — Did he really have the presumption to believe that a transparent mediocrity such as he was, had completely displaced the old man in her heart? This monumental poet of destruction who had finally and irrevocably been defeated in life.

Daive meets Gisèle for the last time in the autumn of 1989. — Some poems by Celan are about to come out in his French translation. They kiss, he says, before parting, after a long day together. At the time of their meeting, Celan would have been dead for nineteen years. Gisèle would have been sixty-two.

Daive’s current paramour, Edith, questions his relationship with Gisèle. — “You made love to her?” She says people are not happy with him. — The betrayal of the poor ailing poet. — Odious from the outside looking in. To be cuckolded by a young kid acting as his friend and companion. So seemingly sensitive to his poetry, his pain. So eager for his guidance on those epical strolls of theirs.

Daive mentions near the end of his memoir, a walk he took along the Seine on a fine spring day with their mutual friend, Joerg Ortner. The conversation turns to holy places, the nature of mathematical proofs, God’s essence. Ortner: “but why am I saying all this? . . . Perhaps it’s the Seine that pushed me . . . No. Ah yes. It’s because we never talk about Paul Celan since he died.”

Nothing for it —

Under the Pont Mirabeau

the Seine…

◊

Ivan Klein published Toward Melville, a book of poems from New Feral Press, in July 2018. Previously published Alternatives to Silence from Starfire Press and the chapbook Some Paintings by Koho & A Flower Of My Own from Sisyphus Press. His work has been published in the Forward, Urban Graffiti, Otoliths, and numerous other periodicals.

Other essays, reviews and poety by Ivan Klein on Arteiodolia→

For information on Ivan Klein’s latest book

The Hat and Other Poems and Prose from Sixth Floor Press

click here →