Interviews: Edleheit & Milder

Ron Morosan

March 2017

I recently had the pleasure of interviewing Martha Edelheit via e-mail and Jay Milder by phone. Both artists are represented in the Grey Art Gallery’s exhibition, Inventing Downtown: Artist-Run Galleries in New York City, 1952-1965 on view until April 1, 2017.

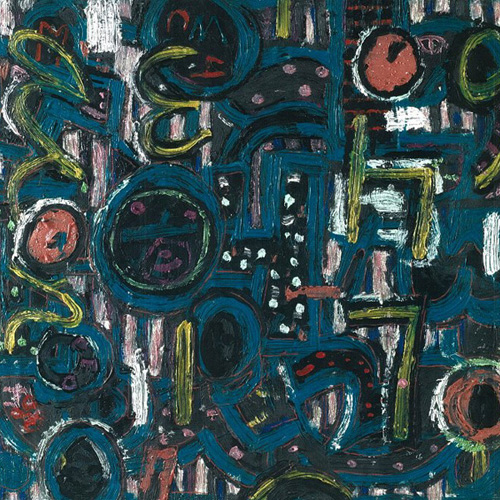

Frabjous Day, 1959, close-up, image courtesy of Arteidolia

Interview with Martha Edelheit

Martha Edelheit lives and works in the countryside outside of Stockholm, Sweden.

Ron: Did you feel that artists were concerned with a strategy for their galleries that could change the direction of art in New York at that time?

Martha: The artists I knew and met were concerned with having a space to show their work, which was quite out of the mainstream. The art that was being shown in the uptown art galleries was primarily abstract expressionism or European abstract work. Figurative art was totally outside the interest of uptown market galleries.

My experience was with the Reuben gallery and then the Judson gallery. I and most of the other artists were creating works that were intended to break out of the ‘box’ of Pollock, de Kooning, Kline, etc. It wasn’t that these artists weren’t admired, but that the urgency to move forward, to create new visions, to have a different dialogue with the viewer and art history, was powerful.

Ron: Abstract Expressionism was becoming a big success. Did you feel you had to go beyond that?

Martha: Abstract Expressionism was not becoming a big success! It was a big success. It was what the uptown galleries were showing and selling. It was what the museums were showing and acquiring! It wasn’t the galleries that would change the direction of the NY art world, it was the artists. The galleries were simply the traditional vessels for presenting the artists. Many of the artists also created alternate spaces, not permanent gallery scenes.

Ron: Was there a lot of argument?

Martha: There weren’t arguments, but lots and lots of discussion, exciting, in depth dialogue. I remember thinking at the time that this was what it must have been like in Zurich in 1914-16 with the Dadaists and Surrealists. It was incredibly stimulating. All kinds of ideas were ‘in the air.’ Nothing was taken for granted. Everything was possible!

Ron: Allan Kaprow to my mind was a visionary. Did he set the bar for discussions?

Martha: Kaprow was part of the dialogue. He wasn’t a ‘guru’ back then, he was just another struggling excited artist trying out one idea after another. He was developing his ideas and he tested them out on all of us! Before he started doing the happenings, he was following the footsteps of Al Leslie, Hans Hofmann and the abstract expressionists. The artists could show what they wanted. The only critique was peer approval. We all hoped the ‘uptown’ viewers would come ‘slumming.’ And they did! The artists and the galleries did not have to sell to stay open. Most of the artists were male, and most of their wives worked at regular jobs to support them. Some of the artists, like Kaprow, were teachers.

Some of the other galleries had more political and social agendas. The Reuben did not. The only agenda at the Reuben was to create meaningful, exciting, provocative, thoughtful work. Though Segal and Oldenburg certainly had strong moral visions, it wasn’t an agenda.

The Judson galley was different because it was part of Judson Church, and they (Rev. Howard Moody) saw their purpose as reaching out to the whole community, and that community was artists (and prostitutes, the homeless, unmarried pregnant teenagers, the impoverished, as well as the local families). The dialogue got even more exciting because it expanded to include dance, music and theater. The happenings and performances became bigger, more experimental. Schneemann, Rainer, Childs, Forti, Drexler, (all women!) as well as Oldenburg and Kaprow and Flavin, Paxton and Brown and Summers and many more.

Ron: At the Grey when we met, you indicated that you had your exhibition at the Reuben and then nothing seemed to happen. Do you feel you know why?

Martha: At the time I was bewildered by the lack of response to my work. I was self taught and thought I simply didn’t know enough or that I wasn’t good enough because I had no art school training. It took me a long time to realize that I was simply not included in a lot of the dialogue by the male artists. If there was a heated discussion going on when I walked into the gallery, it would stop when I entered. Women were not really part of the group, not any of us. And that was taken for granted.

An up and coming male artist colleague came to my apartment/studio and was looking at my work and said, ”You’re the best damn woman painter since Berthe Morisot.” I was supposed to be flattered. It was considered high praise. Being female was a real issue! But it was not one that was talked about or acknowledged at that time (late 50s early 60s). There were artists (male). And then there were women artists.

I had another problem, though again I did not know it at the time. I was married to a doctor and lived uptown. So, even though a male artist could spend his mornings doing the stock market, or a woman artist could have a wealthy family fortune or a famous art critic supporting her work, and with many of the male artists coming from upper middle-class or wealthy families, somehow I was a middle-class uptown lady who didn’t really belong. Ros Drexler once told me that every time my work came up for a grant (like a Guggenheim, etc) someone would say…”Oh, she’s married to a doctor, she doesn’t need it” and the work never even got looked at.

Ron: Dine also had a show there. Was his show successful?

Martha: Was his show successful? He was successful. His work and his presence! He got a lot of attention. He got into Pace Gallery displacing Krushenick! Did he sell at the beginning? I don’t know. He was very broke and struggling. I think he got a stipendium from a collector who took everything in his studio in exchange for enough $$ to live on and buy supplies.

Ron: After the Reuben show, did you feel you would like to be represented by an uptown gallery?

Martha: Of course I wanted to be shown in an uptown gallery. We all did. I wanted my work to be seen, felt, related to. It wasn’t sales that I thought about. I was incredibly naive. I thought of art as something you dedicated your life to, like a monk or nun; it was a calling, not a profession. When I did get a show uptown at Byron Gallery on Madison Avenue in 1966, I took it for granted that the gallery was doing this out of love for my work. Not to pay the rent! Nothing happened. Castelli blushed. John Canaday said I was obscene and refused to review the show. (I showed very large canvases of explicit, genitally exposed, males and females, and many erotic watercolors.)

An uptown friend was really startled at my innocence. She said, “Do you know how much it costs him just to open his door every morning, pay the rent, the electricity, the advertising?”

Ron: Tell me about your painting in the Inventing Downtown exhibition, Frabjous Day? My reading of it is seeing it more as a kind of landscape suggesting the illusion of three dimensional space.

Martha: Frabjous Day is not moving toward landscape, but toward figuration. I don’t know who (what Jabberwock) I had slain, always engaged in arguing with what I saw in the galleries ( I was a very contentious person back then, always battling. My mother was the wicked witch of the west.) My first journal notes were angry discussions with myself about what I had seen that day in the galleries, but I think it was the triumphant joy of this painting that inspired the title! Some of my extension paintings were landscape inspired, specifically, Fishing for the Blue Moon, which was created after standing on the tip of Provincetown Beach at sunset. The full moon stood on the horizon rising and the full sun sat on the horizon setting directly opposite each other, me in-between, shadows of fishermen down the beach. A totally magical moment!

I was also doing a lot of constructions at the same time, many of which have disappeared. And I was drawing imaginary letters, unreadable, but serious, and a series called Children’s Games, which are very stark; armless, or legless, or blind acrobats, dolls, toy soldiers, motorcycle drivers, groups of players (children), circus performers, in distress. The watercolors are a visually logical extension.

The Dream of the Tattooed Lady is very much part of the erotic watercolors. I was fascinated by Japanese Pillow books, (a friend had several), Byzantine and Carolingian/Romanesque 5th-12th century churches. Every inch of the church walls were covered with the lives of the saints, beheaded, drawn and quartered, flayed, eyes gouged out, breasts cut off, dismembered in every imaginable way. These images are all story telling, and my fantasy dream images are also story telling.

I also was intrigued by tattoos. Levi Strauss, in Triste Tropique describes tattoos as the 1st art form, the first painted surface. They always tell a story about the person whose skin is made into pictures. When I was a child, I had a classmate whose parents designed cutout doll books. We were invited to see how they did this at her home and I used many cutouts in my often violent childhood games.

Ron: Were you involved in any Feminist discussion or activist groups?

Martha: My interaction with the women’s movement did not happen until the early 70s. So, there is little that is useful in this period. It was still male dominated, and I had little success in the gallery or art market scene. Most of my friends and colleagues were male artists. (I remember O’Keeffe telling me that when she went to Lake George with Stieglitz and all his male artist friends, she was treated as a mascot.)

Though I had a very strong show at Byron Gallery in 1966 and showed many of the watercolors and my Flesh Wall paintings, everyone came to the opening, but nothing happened. No followup. No second show. No invitations to be in group exhibitions.

It never occurred to me that being female was a big part of the problem. Now I wish I had known about and made contacts with other woman artists at that time.

Ron: I really like your drawing Dream of the Tattooed Lady of 1961. What’s going on with that series?

Martha: Different materials offer different challenges and for me every idea has required its own material. What you say with ink and watercolor on rice paper is very different from what you say with the same materials on hand made rag paper. What you say in film is not what you say in clay, though one can feed into the other or be used together. Acrylic is not oil paint. Each demands its own way of thinking and using. There is a lot of personal life material that is behind these works, a lot of personal fantasy and story telling, and, what I would call today, wry political commentary and satire.

Ainsop – that which is without ending, 1958, courtesy of the artist

Ainsop – that which is without ending, 1958, courtesy of the artist

Interview with Jay Milder

Jay Milder lives in Easton, Pennsylvania and New York City.

Ron: What was the scene like in the late 50’s?

Jay: In those days there was no money, no uptown. All the artists in New York could fit into the Cedar Bar- no more that 200 or so artists.

Ron: What was the atmosphere like, the issues going on?

Jay: Abstract Expressionism was very important. And there was a big concern with the spirit in art.

People were reading Madame Blavatsky and I was studying Theosophy.Blavatsky was an influence on Abstract Expressionism. But, then the influence of John Cage started to come in. This was through Alan Kaprow. They were influenced by Marcel Duchamp. But we felt it was a designer idea and not concerned with meaning. I was friends with Kaprow and one day he drove Bob Thompson and me out to Rutgers. (Bob Harding made the connection between Kaprow and me. He’s been forgotten and should be re-discovered.) We met Bob Whitman and Lucas Samaras there. They were Kaprow’s students. They were planing the Happenings. I was in the first Happening Kaprow did.

Ron: What galleries were you involved with?

Jay: I started the City Gallery with Red (Grooms) and was also one of the founders of the Phoenix Gallery.

Ron: Was there a committee that formed to judge members and shows?

Jay: Yes, but it changed. We tried to get Oldenburg in to the Phoenix, but he was rejected by one of the panels. I decided to quit the gallery after that. ( I think it still exists. It was the longest lasting.)

Ron: Could you talk more about Madame Blavatsky?

Jay: Blavatsky’s concepts dealt with the Platonic concepts and a theology. This was very much in the air. She was the main teacher of the 20th century. She taught that Platonic philosophy dealt with everything. Artists understood that.

But then the designers brought in the Aristotelian and the Materialist. The designers understood the geometry but not the theology. They wanted an Aristotelian art.

This was what Hitler’s museum people wanted. They thought Jewish art was too abstract. My art was coming from theology and hermeneutics.

I’m writing a book called The Genesis of Western Alienation.” I want to show how in Eastern religion children are born spiritually pure. The Christian religion teaches that children are born bad, original sin.

Ron: So what kind of things were you thinking about and putting into your paintings?

Jay: I was coping with cognition; I don’t like cognition.

Ron: The still life painting in the Grey Gallery exhibition Pot of Flowers, can you talk about what your were painting at that time?

Jay: I’ve always painted still life and figurative. So at that time I got into something in Puerto Rico and they gave me a show at their brand new museum and they had me on TV. They made a big deal out of it. So all the Puerto Rican artists were picketing, as well they should. Sheila and I just went down there instead of going to Provincetown. We had a friend who had a house in old San Juan. I became a star in Puerto-Rico. Have you ever been to Puerto-Rico?

Ron: No, I’ve never been there.

Jay: It went very well. I had a great time.

Ron: Do you know if the painting in the Inventing Downtown exhibition was in that show?

Jay: Yes, it was.

Ron: It seems you were in the international scene at that time.

Jay: Well, I guess all of a sudden I was. I told an older artist, ( I won’t mention his name.) about my experience there, and then he and his wife went the next summer to try to get something set up. I don’t know if it happened. It was very funny.

Ron: American artists at that time, I don’t think they were getting a lot of opportunities to show overseas, were they?

Jay: There were no Americans there at that time. So it was before that time.

Ron: Did the museum in Puerto Rico buy a painting also?

Jay: Yes, they bought two paintings. Not only that, they asked me to teach there. And I told them I don’t want to teach; I wanted to work. You know in the old days if you taught you were a bad guy. Nobody taught. But there they wanted me to teach and to open up a gallery.

Ron: One thing that for me stood out about Inventing Downtown is that it was all about the artists: that was the art scene. You didn’t have many curators.

Jay: There were no curators, no art historians. And many artists had not really gone to college. They went to art schools or apprenticeships. GI or whatever. It wasn’t Paris. There, in Paris, there were only GI’s.

Ron: When I was at the opening of Inventing Downtown, I thought this might be the way an art world would look if artists took it back.

Jay: Yes, what happened is it went into commercialism and then we end with floating cows.

Ron: Now, Wall Street is involved.

Jay: Yes, now that’s only what is going on. They don’t want art. It’s not art; it’s anti-art.

Ron: I wanted to ask you: did you study with Hans Hoffmann at all?

Jay: Yes, I did.

Ron: As I understand it Hofmann’s concept of push-pull, where a still life or landscape would be looked at in terms of its abstract color and form relationships, I think that must have been a very innovative way of thinking at that time, no?

Jay: Well, you know I’ve always been involved with physics. You see that was when art, and physics and meta-physics and everything were combined. It was so Eastern. You see in the 60’s how it turned Western and it becomes linear and Aristotelian. That’s what happened. We came into the Aristotelian age, and that’s what we’re ending up with.

Ron: That’s materialism, the obsession with materialism.

Jay: Yes,

Ron: Can you talk a bit about Provincetown?

Jay: Yes, that was wild. It was like an artists’ village. It was a little like when I was in Paris. Montparnasse and like that. There you had an apprenticeship. There was no school. I had a table at the Norte Cafe in Montparnasse and there was this one guy named McIntyre. He was seventy-five and I was 18. He was the head of the philosophy department at Berkeley. He was on leave, on sabbatical; it was his last year. There were other guys. One was a physicist. Art historians. One from Australia who was a way out guy. So it was like a seminar. But the physicist knew Brancusi and would visit him. For a short while I lived across the street from Brancusi.

Ron: There are a lot of events going on along with Inventing Downtown. Oldenburg and Bob Whitman are speaking.

Jay: I didn’t get to that, but I’m speaking this coming week at Mimi’s museum.

Ron: Good, I’ll come to that.

Jay: It’s something about Provincetown.